The Necessity of Green

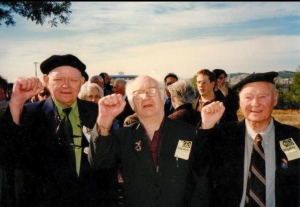

David Betteridge writes critically and creatively about the artwork above, Nature writing, Bertolt Brecht, and eco-communism.

The idea of nature contains, though often unnoticed, an extraordinary amount of human history - Raymond Williams

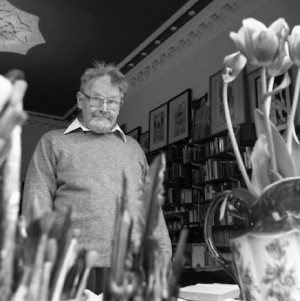

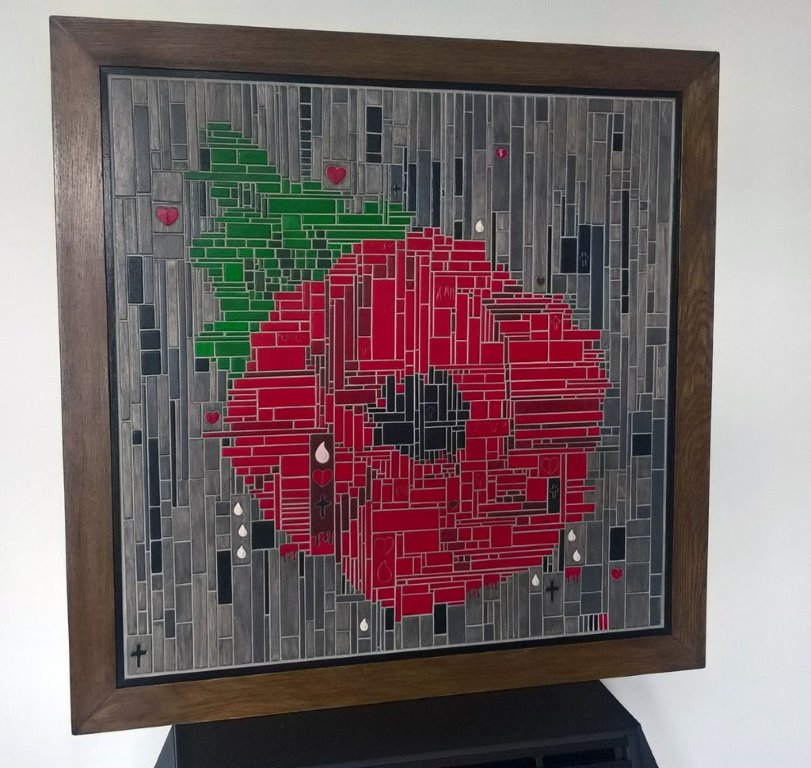

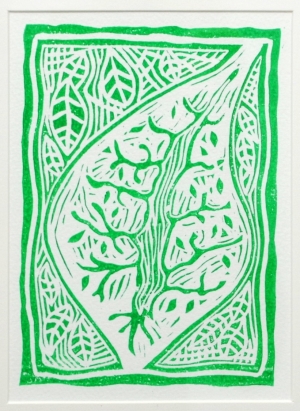

What you see above is a lino print called “Leaf of Tree”, by Owen McGuigan.

It hangs on the wall above my computer at home, is mounted on white card, and is surrounded by a broad hardwood frame. It measures five inches across by seven inches tall. Looking at it, as I often do - it draws my attention to it, inspiringly - I find that it invites two kinds of looking: one from above, so to speak, as if I was a bird gliding over a fertile landscape, and the other slower, more detailed, as if I was an insect prospecting this way and that way at close quarters. How does this “Leaf of Tree” image strike you, I wonder?

For most people, probably, the thoughts and feelings that the print arouses will be pleasant ones, and for three reasons. The first reason is physiological: the highest-density part of our eyes’ retina is most sensitive to green, so responds to that colour with greatest acuity. The second reason is aesthetic: the placing of one larger leaf, stylised, within a pattern of smaller leaves is very skilfully handled; we look, and we recognise beauty. The third reason is associative: the image triggers memories in us of previous leafy encounters, whether in the real world, or mediated through art or literature.

Those 35 square inches of art might stand for three or five or 35 acres of green growth, or more, or for the whole world if you think so; or they might stand for some smaller singular Dear Green Place, dear only to you. For me, the fresh green of “Leaf of Tree” conjures up a summer’s day in a wood in Argyll. I hear the waves slapping on Loch Etive, not far from where I stand. The sun is shining directly on, and through, a panoply of sessile oak leaves, highlighting their veins in all their intricacy. I am also reminded of William Morris’s lovely plant designs, particularly “Acanthus”, “Orchard” and “Willow Bough”.

Building on these or similar associations, we might even go on to interpret the colour green and the idea of “green” in a symbolic way, seeing in growing things the very principle of life, as Walt Whitman did when he wrote his Leaves of Grass:

I guess it must be the flag of my disposition,

out of hopeful green stuff woven...

I guess it is a uniform hieroglyphic...

Growing among black folk as among white...

I give them the same, I receive them the same...

All goes onward and outward...

and nothing collapses...

Having images such as “Leaf of Tree” on display at home, or stored electronically, is pretty commonplace. Looking at them, we can readily feed our senses and our imaginations, for the reasons given above. It is also commonplace to want to read and be reminded of green things, especially in dark times such as we live in now - and when are times ever not dark? Books about Nature are consistently in lists of best-sellers.

During the recent Covid-19 lockdown, my “Leaf of Green” took on especial significance for me. It inspired me to wrestle some green thoughts into a chapbook of poems, including the one given below:

While the pot boils

(Looking out of my kitchen window during the Covid-19 pandemic)

Even in these dark days,

the world does not forget to green

and grow.

My neighbour’s apple-tree progresses well,

no longer bare twigs, but leaves and flowers.

With fruit to come, it gives sanctuary

to a pair of nesting wrens,

who get on busily with everything

that their lives demand,

heedless of what we humans know,

or do not know.

The tree waves and bends

in the frequent wind.

I note it does not break.

Like the wrens, it is industrious.

How readily Earth’s habitats renew,

recycle, and remake!

A critic of puritanical bent might argue that such “nature worship” or “nature wallowing” as is found in the above poem - and in Nature writing generally, perhaps - is a deplorably “escapist” habit, a turning away from the “real” business of dealing with the world. George Fox, founder of the Society of Friends (Quakers) was an early example of this stern and restrictive school of criticism. In 1670, or thereabouts, he wrote to his followers as follows:

And therefore, all friends and people, pluck down your images; I say, pluck them out of your houses, walls, and signs, or other places, that none of you be found imitators of his Creator, whom you should serve and worship; and not observe the idle lazy mind…

Later, and famously, from a secular, communist standpoint, Bertolt Brecht wrote as follows, apparently as puritanically as Fox, but significantly not quite:

To those born later

Truly, I live in dark times!

The guileless word is folly.

A smooth forehead

Suggests insensitivity.

The man who laughs

Has simply not yet had

The terrible news.

What kind of times are they, when

To talk about trees is almost a crime

Because it implies silence about so many horrors?

That man there calmly crossing the street

Is already perhaps beyond the reach of his friends

Who are in need?

Being a great poet, and a man fully alive, Brecht carefully avoided the extremism that was found in Fox, who went so far as to prefer grey to all other colours. “Almost a crime,” Brecht declared; therefore not a crime, although some on the Left might still think it is, trapped in the notion that tree-talk can only be a turning aside from the realities of the class struggle, and therefore a holiday from the building of socialism. No, Brecht was careful to keep for himself a certain licence to talk about trees, and write about them, and delight in them. These things he did throughout the years of the Second World War and Cold War, up to his swan-song Buckow Elegies. Consistently, he used trees as an emblem for pleasure, well-being, and for continuity across generations.

“Lovely trees,” he exclaimed in “Finnish Landscape”, and “Such scents of berries and of birches there!” He saw no need to repress his delight in Nature. It resurged again and again, gaining expression in other poems that he went on to write, often about gardens, including, most luxuriously of all, his friend Charles Laughton’s garden on the Pacific coast near Los Angeles. Brecht singled out the fuchsias for praise: “Amazing themselves with many a daring red”.

Always the dialectician, Brecht contrived to plant negatives among his positives, creating a complex context for his celebration of green beauty. So, in “Finnish Landscape”, written in 1940, with war spreading from country to country and across continents, he wrote:

Dizzy with sight and sound and thought and smell

The refugee beneath the alders turns

To his laborious job...

[He] sees who’s short of milk and corn...

And sees a people silent in two tongues.

And in the Californian “Garden in Progress” (1944), he added to his picture the fact that there was “crumbling rock” destabilising the garden. Even as the gardeners worked to finish their planting, “Landslides / Drag parts of it into the depths without warning.” Meanwhile, the poet was aware of the gunfire of warships exercising off the coast, and thought of “a number of civilisations” ready to collapse.

The same delight in the things of Nature as Brecht’s, again voiced in communist terms, and again set in a complex context, is found by the wagon-load in William Morris’s News from Nowhere (1890). Near the end of this imagined visit to a future commonwealth, Morris’s alter ego William Guest is told by his guide, Ellen, that:

O me! O me! How I love the earth, and the seasons, and weather, and all things that deal with it, and all that grows out of it...

Here Morris’s green utopia is used as a method of criticising capitalism, of opposing it, and of rejecting it, while at the same time re-imagining how a society might better function in future. His utopia is as much a dramatising of a communist “structure of feeling”, as defined by Raymond Williams, as it is an outlining of a political programme. It is an early example of eco-communism, where Green and Red go hand in hand, albeit simply.

There is an eloquent passage in Ernst Fischer’s The Necessity of Art where he quoted Brecht regarding the same critical use of utopia as Morris deployed:

Dreams and the golden “if”

Conjure the promised sea

Of ripe corn growing...

To Brecht’s “Dreams and the golden ‘if’” we might add our own corollary: “Hope and the green leaf”.

II

So far, we have looked at the “Leaf of Tree” image as a finished product, its only context being provided from our own store of memories of similar green things, and images of things, and writings about them. Your store will be different from mine, of course, although I guess - I hope - that there will be enough commonality between them for us to agree that “Leaf of Tree” is well worth looking at, and looking at many times, and that doing so is a rewarding experience: in a nutshell, that it is life-affirming.

Now it is time, in the second half of the essay, to show the process by which “Leaf of Tree” came into being, and to put it in its full context - a context that includes its artist, its time and place of production, and the culture out of which it came and into which it feeds. Knowing these extra things about the image is unlikely to change our first opinion of it, but may give depth and confirmation to that opinion, and increase the range of associations that the image prompts in us. “Oh no,” a formalist critic might protest, narrowly, “we should only be concerned with what lies within the frame.” We, preferring a cultural materialist perspective, will not be deterred. As when we get to know anything or anyone new, so with “Leaf of Tree”: we want to ask of it, Where are you from?

Here is where “Leaf of Tree” is from: namely a garden shed on the very boundary of Glasgow and Clydebank. The artist is Owen McGuigan, a former shop-fitter, now retired. He is well known in Clydebank and beyond as Clydebank’s best archivist and celebrator. His principal medium is photograph and video, although latterly he has also used drawing, print-making, jig-saw and wood panel burning as media for his vision. Visit his website here, and be bowled over by its very great volume, beauty and range of reference. All in all, there are sufficient images archived on Owen’s website to satisfy legions of social historians and Bankies wanting a visual record of their hometown, legions of art-lovers, and to inspire legions of poets.

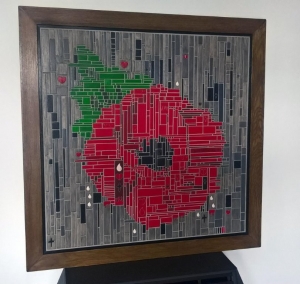

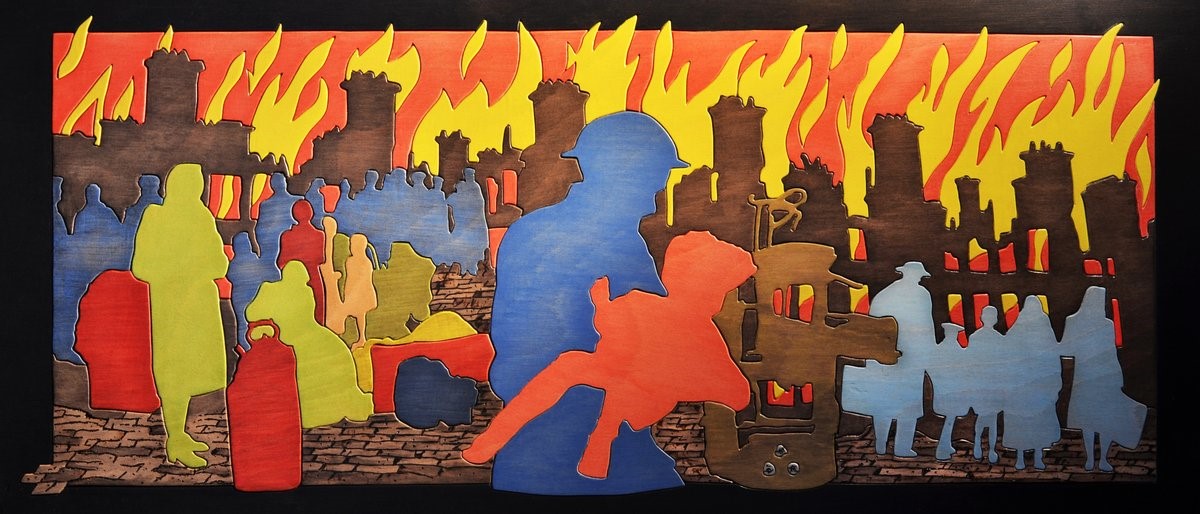

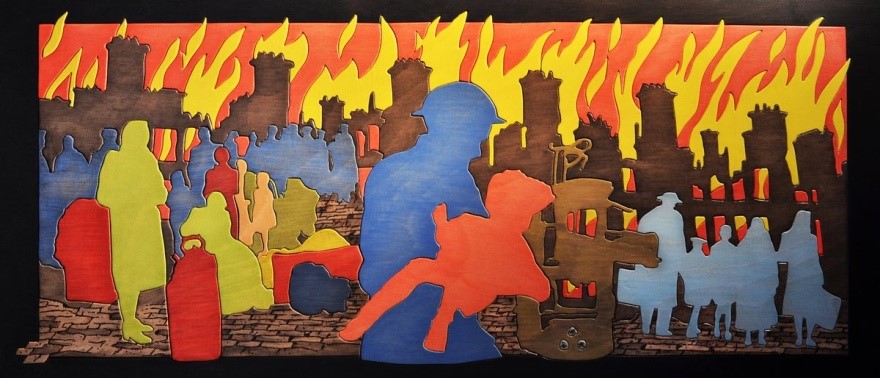

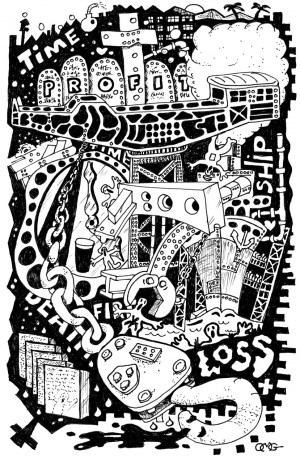

Owen has contributed to the Culture Matters website, on the subject of ship-building’s double legacy in “Profit and Loss” (28 January, 2017), and on war and peace in “The Pity of War” (23 July, 2018) and “No More War” (10 November, 2019).

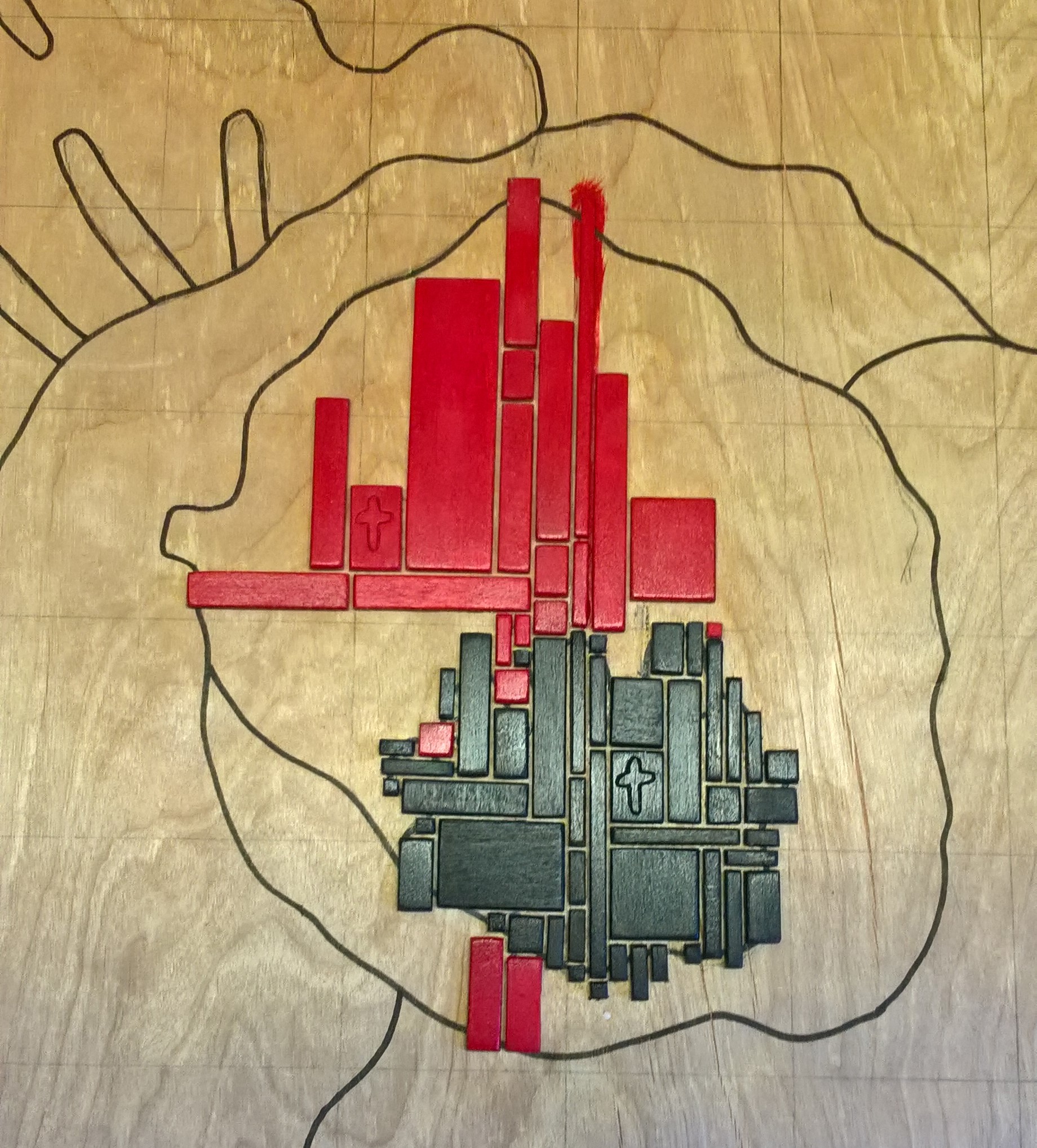

I have picked out a few examples of Owen’s work below, to keep his “Leaf of Tree” company: -

Trees in winter, Dalmuir Park

A garden game, devised for grandchildren during the Covid-19 lockdown

Cleaning up the Forth & Clyde Canal: a recent photo

The Clydebank blitz: a jigsaw composition

Elegy for Glasgow School of Art: aftermath of its second fire, June, 2018

Profit & Loss: Ship-building anatomised

Dogwood and spider

Even these few examples give a good impression of Owen’s range of styles and subject matter. What unites them is a strong shape, a clear content, and skill. They are all labours of love, produced in Owen’s leisure time. This fact gives them a special significance, rescuing them, and rescuing Owen, from any nexus of commodities and marketplaces. In Raymond Williams’s words:

The real dividing line between things we call work and the things we call leisure is that in leisure... we make our own choices and our own decisions. We feel for the time being that our life is our own.

The garden shed that is pictured above is only one of Owen’s favoured workshops. That is where he works when he works alone. On other occasions, when he works with others, sometimes as a tutor, sometimes as a learner, always collaboratively, then he has two other places to go to, both close to home. One of them is an arts centre in Dalmuir Park, in an old park superintendent’s house; the other, rejoicing in the name “The Awestruck Academy”, is in a defunct snooker hall in Clydebank’s pedestrianised town centre.

Ten thousand such cultural hubs across the land, for community use, sited wherever “To Let” signs are commonest, would serve the people there in the way rising sap serves a tree. Ten thousand such hubs devoted specifically to socialist and trade union work would specifically serve the labour movement. There are several pieces on the Culture Matters website exploring this notion, notably Rebecca Hillman’s “Rebuilding Culture in the Labour Movement” (27 November, 2017), Mike Quille’s “Culture for the Many, Not the Few” (13 December, 2018), and Chris Guiton’s “Profound New Visions of a Better World” (10 June, 2019). They underpin the argument being advanced here.

Regarding the two cultural hubs in Clydebank that Owen favours, and is fostered by, he mentions them in a contribution he has written for this essay, giving the “Leaf of Tree” back-story. From it, you will realise that the image that is at the heart of this essay is unique: it is the first, and so far the only print made from Owen’s linocut:

I have had a fascination about trees since I was a boy, from climbing them in Whitecrook Park with my two sisters in the 50s, and our mum taking us berrypicking at Blairgowrie during the school holidays, where on our day off my two sisters and I would go to the forest around the loch and light camp fires. I can still smell that. Later in life, my nephew David and I did a lot of hill walking. We walked the West Highland Way together, and I loved walking inside a silent forest. The family and I even built a cabin up at Carbeth, in the hills, which we had for twelve years before vandals set fire to it.

So, over the years, trees have been a recurring theme in my work. More so when I joined the Dalmuir Park Art Class in 2013. We did a lot of nature-themed projects. Last year we all did a big tree mural, and over the year we added various elements to it reflecting the seasons. I made a video of this project:

Usually, when I sat down at the art class to start a lino- cut, I never planned what I was going to do. An idea of a tree inside a leaf popped into my head. The final title was a play on the words “Tree of Life”, an image that has always fascinated me. I made some Christmas decorations of it, although it was a lot of work, as they were handmade.

The first linocut that David saw was at the Awestruck Academy in Clydebank, on a board that someone had set up with several linoprints. David was taken by the image, and I said I would print one for him. I looked through all my linocuts, and, as usual, it was the one that was missing! Then I remembered that Sandra Anton, the Community Ranger that runs our art class, liked the linocut herself and wanted to display it at home, so I let her take it. I asked her, but she had been decorating and stored it somewhere, and couldn’t find it. I then did a new linocut especially for David and printed it for him. This was the inspiration for David to create his latest poetry book.

III

Looking again at Owen’s “Leaf of Tree”, taking into account both the context and the process of its making, we can agree that the image suggests much more than a bit of green growth. We can agree, in reality and metaphorically, that a leaf - any leaf, anywhere and everywhere - is sustained by a twig, and the twig is sustained by a branch, and the branch by a tree’s bole, and the bole by a system of roots, and the roots by the soil into which they dig down and spread. And we can agree that the tree - any tree - might well not stand alone, but is part of a greater habitat.

So Owen, by analogy, is a vigorous part of a pretty extensive living, growing and interdependent People’s culture, rooted in Clydebank, but reaching further by means of the internet. The culture that he and his co-producers spring from, and feed back into, is a foreshadowing of the greater culture to which Socialism will lead; but it is not only a foreshadowing. It is also a preparation for that greater culture, sharing good practice and educating desire now.

Brecht, as we have noted, kept an appreciative eye open for trees wherever he went. He was speaking equivocally when he commented that, during political crises, “To talk about trees is almost a crime.” No! On the evidence of Owen’s image of a green leaf, and all the associations it carries for us when considered in context, as in this essay, we can state, unequivocally, that not to talk about trees is almost a crime.

The green leaf delights the eye,

and leads the mind to a hundred habitats

where it may either rest or roam.

Hope and the green leaf inspire the wish

that such green habitats - where humankind

keeps step with Nature’s ways - might be

for all of us our proper home.

Labour and hope, if only shared

world-wide, and people-wide,

will make at last that vision real,

bringing to detailed life the concepts

of our commonweal.