But Billionaires are People Too!

Fran Lock introduces her quarterly poetry column

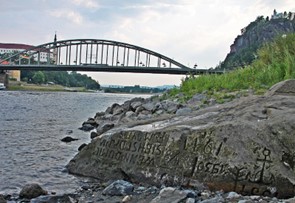

Amidst rolling news coverage of the Titan sub disaster, I scrapped the first draft of this quarter's column, and began again, forcibly struck as I was – as I continue to be – by the alarming differential of media attention, public sympathy, and international aid between those with money and those without. While futile search and rescue efforts were underway for the OceanGate submersible, a tragedy of arguably far greater magnitude was occurring off the coast of Greece, where a fishing trawler carrying more than 700 “migrants”, including over 100 children, capsized. At time of writing, 82 passengers are confirmed dead, and over 500 people are still missing. The UN reports that since 2014 more than 26,000 people have died or gone missing in desperate attempts to migrate by sea. It felt important to address the inequality of response afforded the poor and vulnerable, on the sea and on the land.

First, to briefly recap: the Titan sub was an unregistered, unregulated experimental craft, operated by OceanGate, and running $250,000 “tours” to the wreck of the Titanic for its billionaire passengers. Among the dead were French explorer Paul-Henri Nargeole, British born billionaire thrill-seeker Hamish Harding, British-Pakistani billionaire Shahzada Dawood, along with his 19-year-old son, Suleman. Last on the list, the CEO of OceanGate and developer of the sub, Stockton Rush.

Rush might politely be referred to as a “character”, one with an almost breathtakingly reckless attitude toward health and safety. As Ash Sarkar among others has reported, Rush gave a telling interview with the Unsung Science Project in 2019 where he described safety concerns as, after a certain point, “pure waste”, claiming “it really is a risk reward question […] I think I can do this just as safely while breaking the rules.”

Others vehemently disagreed, included David Lochridge, former director of marine operations at OceanGate, who was reportedly fired after raising concerns about Titan's safety in 2018. According to numerous sources, OceanGate refused to have the testing of the experimental vessel monitored by an independent organisation that would have ensured it met accepted technical standards. Lochridge claims OceanGate were “unwilling to pay” for such an independent assessment, and that Rush ignored repeated warnings that the sub's viewing window was safe only to a depth of 1,300 meters (the Titanic rests at nearly 4,000 meters below the ocean surface). In 2018 over 40 deep-sea explorers, industry experts, and oceanographers signed a letter to Rush, urgently requesting that experts be allowed to monitor testing of the Titan. Rush declined to comply. Instead, he continued to make public pronouncements about the ways in which regulation “stifles innovation” with an unshakeable and utterly misplaced confidence in himself and his untried technology.

We now know that the craft imploded shortly after it began its 2.4 mile descent to the wreck of the Titanic. The US Navy reports that it picked up sounds of this implosion on Sunday, soon after the sub lost contact. A horrible, but mercifully quick way to die, with those on board probably having little time to register what was happening to them. Yet the media continued to breathlessly cover the multinational “rescue” efforts comprising teams from the US Navy, the Canadian and US Coast Guard, a French Remote Operated Vehicle Team, a British Royal Navy submarine expert, and specialists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. The search involved classified undersea listening equipment, a deep-sea winch, search planes, numerous ROVs and a submarine, to the tune of over one million dollars. Over the last couple of weeks, as “rescue” turned to recovery, and debris from the sub was bought to the surface, the mainstream media's gaze was once again directed towards the gruesome tragedy.

The worst excesses of capitalism

This recap serves to illustrate a number of different points, depending upon the angle you approach it from. Mostly, the loss of Titan has been pitched as a morality tale, where a monumental sense of entitlement and a fatal lack of humility met in a moment of catastrophic and vividly embodied hubris. It provides yet another example – if any were needed – of what happens when companies prioritise economic success over safety, where “innovation” becomes the fig-leaf covering cut-throat financial competition. What happened to the Titan is an exemplum and a microcosm of deregulation, the worst excesses of capitalism in action. It's a story – to quote Sahkar – about “the judgement-warping nature of extreme wealth”. Rush believed he knew better than all of those experts; his passengers believed their money gave them safe and privileged access to the outer edges of experience.

What else is there to say? I was contemplating this as our morally compromised ex-PM weighed in via his Daily Mail column to describe the passengers of the Titan as “heroes”, who died while “pushing out the frontiers of human knowledge and experience” and that their tourist trip to the wreck of the Titanic filled him with “pride”. Curious, even by Daily Mail standards.

But the Tory government – and economic elites generally – desperately need the irresponsible personal choices of privileged individuals to be rebranded as in some way inherently beneficial for wider society. With equal desperation they need a mainstream media content to peddle the myth that when rich people do it, “risk-taking” is, in some nebulous and ill-defined way, noble, brave or glamorous. They need this toxic ideology to legitimate their daily gambles with financial markets, health and housing infrastructure, and with our very lives. Such logics brought us the housing crisis of 2008, the callous mishandling of a global pandemic, and the heart-rending tragedy of Grenfell Tower, where the foolishness and greed driving deregulation meant that working-class people could be legally housed in fatally unsafe properties.

In this way the rich have always recuperated their stupidity and failure as value, however many of us (or each other) they kill along the way. The double standard is astounding. I find myself thinking about the way that victims of the Hillsborough disaster were blamed for their own deaths and injuries, by government, by the police, and in the press. We saw this victim-blaming post-Grenfell too. We see it every day in the demonisation of the most vulnerable amongst us, whose “lifestyle choices” are repeatedly figured as solely responsible for their poor health outcomes. If you're rich you can do no wrong, money sanctifies you. If you're poor, you can never be innocent or suffering enough not to be blamed for your own sad fate.

I am thinking once again about the impossible choices people make when they undertake a small boat (sometimes a trawler, more often just a dinghy with an outboard motor) crossing for the chance of a better life. Many are fleeing war, persecution, and various registers of abject poverty in their own country. They get on those boats, not in the confident expectation that some aura of specialness will protect them, but because the slim chance they have in the water is better than the no chance they have back on land.

Research conducted earlier this year by Liberty Investigates found that in November of 2021 hundreds of vulnerable migrants appear to have been abandoned to their fates when the UK coastguard “effectively ignored” reports of small boats in distress. Around 440 would appear to have been left adrift after the coastguard failed to send any rescue vessels to 19 reported small boats carrying “migrants” in UK waters. While government rhetoric paid lip-service to concerns by denouncing smugglers and traffickers for “endangering lives”, it is telling that in four cases from November 2021, 'reconnaissance planes and drones entered the airspace' near the vessels in distress, but that these aircraft were incapable of providing direct assistance to those aboard. They did nothing to prompt assistance to be sent either.

According to Tech Monitor, in the five years to 2022, the UK had spent more than £1 billion on surveillance technology for use in the Channel. None of that was earmarked towards rescue efforts. Right-wing discourse surrounding “migrants” entering the country on “small boats” often centres on the irresponsible nature of their “choice”. Alive and well is the argument that if people undertake such a dangerous and “illegal” journey, they must face the consequences and expect little or no help.

So what makes five individual members of a wealthy elite “heroic” protagonists in a tragedy, and the “migrants” aboard small boats an expendable mass of illegal personhood in which no one face is distinct or memorable? The Right – in the UK and abroad – operates a sick hierarchy of grievability that says some lives are worth neither saving nor mourning. I make this observation in the context of the so-called Illegal Migration Bill working itself through parliament. The Bill sets out a plan that will effectively render the asylum claims of anyone who arrives “irregularly” into the UK “inadmissible”. The Refugee Council quite rightly points out that there is little or no evidence that the measures set out in the Bill will act as an effective deterrent to those crossing the Channel in small boats. The Bill does nothing to tackle the reasons people undertake such dangerous and difficult journeys, it merely criminalises and further persecutes those who have lost everything.

Meanwhile Tory talking heads have apoplectic Twitter-fits at anyone who dares to point out the unequal sympathy with which sinking billionaires and capsizing refugees are treated, decrying any such statement as poor taste “political point-scoring” driven by an absence of “compassion”. The billionaires are “human beings”, they bleat. Billionaires are people too! We also saw this after the queen died. Republicans were exhorted to remember her “humanity”, as if humanity were some miraculous quality and not the generic condition of everyone alive from Vladimir Putin to Britney Spears. Furthermore, it's worth remembering that theirs is a Schrödinger’s humanity: an arbitrary rhetorical expedient, it phases into existence at the precise moment that scrutiny is applied. We're constantly told that the rich and powerful transcend our mere mortal existence; they spend their entire lives within the hazy, elevated aura of economic privilege, with all the exemptions and special dispensations that implies. They're not us. They are better than us. But if that is the case, then it's a bit much to expect readmission in the final extremis.

“Sympathy” and “compassion” are infinitely renewable resources. They are painfully finite. An investment of effort and attention is required to bring them forth, and the burden of this giving is not shouldered equally by the rich and powerful. I've said it once, I'll say it again: our sympathy simply cannot stretch to meet the irrational demands of our oppressors and class enemies to be loved. Sympathy extracts energy, it requires courage. It is an expression of solidarity and care. It isn't equivalent to good manners or tact. It does not mean agreeing to be silent in the face of injustice. And when we do feel and express sympathy with the rich, what happens to it? It is swallowed up by an enormous void, a void that doesn’t recognise our humanity, or the humanity of the most vulnerable amongst us. Whose humanity is fit to be recognised?

Poetry that insists on a reckoning with power and the powerful

The poems below make room for a radical expression of sympathy. They do so in various ways: through the direct and compassionate acknowledgement of the lives that have been lost; by affording those lives the space of the page; and by foregrounding them in consciousness with a meticulous care seldom afforded them as human beings. These are also poems of accounting, poems that insist on a reckoning with power and with the powerful, as the chief duty that we owe to the dead. All perform the special dual operation of poetry: addressing two audiences simultaneously, so that at their most furious and excoriating they also give us their most tender expression of care.

Sunken Levels

By Jim Aitken

It was the first item on the news

for days, the Titan submersible

taking a group to see the Titanic wreck.

The loss of life was indeed tragic, as was

the £200,000 fee charged to those on board

to view the wreck and never return home alive.

Less newsworthy was the unnamed boat

that sunk in stormy seas off the Grecian coast

with the loss of eighty lives, mainly Pakistanis.

And less newsworthy the thirty-nine Vietnamese

lives lost, found inside a container lorry. Neither

the Pakistanis or the Vietnamese had names, it seems,

Unlike those in the Titan submersible who were all

named. The difference was all to do with wealth,

with class status, for the migrants were simply poor

And those in the submersible had cash to throw away.

It reminded me of Bezos and his rocket into space

thanking his Amazon workers for this unseemly waste.

With a media that worships wealth and despises the poor

both at home and abroad, though especially abroad,

the difference in coverage was class-ridden and predictable.

Yet they say that class is over these days; that it doesn’t

matter anymore. Yet, there is no level to which the wealthy

will sink to stay wealthy – should this not be learned anew?

Or do we all sink together so that the wealthy can

continue to be wealthy at the expense of the world’s poor

as the land burns and the sea levels rise to sink even them?

Or do we instead talk of rich and poor all over again and give

place for egalitarian dreams to flourish; to challenge the all-

consuming, insatiable appetites of the few and raise the many?

'Sunken Levels' by Jim Aitken addresses the sinking of the 'unnamed boat' directly. The poem is a meditation on the backgrounding of individual lives (and deaths) that reduces poor, brown human beings to absent subjects within wealth-obsessed neoliberal culture. It also calls our attention to the invisible nature of class itself, and the ways in which a collective denial of its existence only serves to perpetuate harm. The poem takes on the idea of sinking in both its figurative and literal sense: poor people sink beneath the threshold of attention; class is a submerged but ever-present threat to life. One of the most striking things about Aitken's poem is the way in which it recognises the passengers on board the Titan as fellow victims of this mindset. Only in a society that venerates money, and where the glamour of wealth is allowed to generate its own aura of invincibility, would you find those willing to pay £200,000 to descend 4,000 metres below the ocean surface.

Aitken's poem operates with deceptive simplicity: the reader is lowered down through levels of newsworthiness, from billionaire submarine passengers to Pakistani refugees, to ‘the thirty-nine Vietnamese / lives lost, found inside a container lorry.' By expanding the focus of the poem to encompass those lives, Aitken shifts the poem from the binary of basic comparison to evoke a more complex global enmeshment in the machinery of capitalism.

In the eighth stanza the poem performs a reversal and begins to engage with the act of restitution and 'raising'. While individual lives may be irrecoverable, the poem dares to hope that as a society we are not beyond redemption; that we might be propelled to the surface, might 'raise the many', through a vigorous and collective questioning of the systems that dominate our lives and the cultural myths they spin around us.

Land Law in England 1070-1890

By Patrick Davidson Roberts

Four years from the battle they cut the fields with salt.

The terror-tongue amongst us and our own old words burned out.

They held us down as numbers: our lives, our homes, our cattle.

They bound us in their catalogue, ten years from the battle.

These few months from Smithfield, where his promises made fools.

So you are you shall remain and worse. The law of rule.

They broke upon us as a curse. We broke ourselves to yield

and the rain fell all the harder, these few months from Smithfield.

Weeks on from St George’s Hill; our work there done in vain,

our captains sent to silence, the gangs and mob both came

to meet the spade with violence and beat us down until

it is only words that grow there, now, on St George’s Hill.

Days toward the devil’s smoke, our lives lashed as our harness.

Their rents and fences hammered in, they pointed us to darkness.

Named it law and rightly done, to send us from the fields to choke.

To slum and factory, illness, death, in the devil’s smoke.

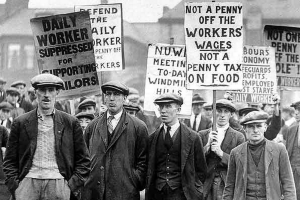

'Land Law in England 1070-1890' by Patrick Davidson Roberts takes a different approach. The poem engages the broad sweep of history: using the cadences and rhythms of an early-modern folk ballad, it tells the story of how the rich cement their will to power as written law and moral right. They do this to crush generations of working men and women, from agrarian commons, through enclosure and privatisation, to the Industrial Revolution and the grim reality of work in factories, mills and mines. As with Aitken's poem the poor are disappeared: physically removed from the land they used to tend, but also 'held down' as numbers, bound 'in their catalogue', reduced to statistics, figured as faceless economic units to be administered, or as problems to be solved within the language, apparatus, and collective imagination of the state.

While Roberts' poem covers a wide span of historical ground, from the Norman Conquest, by which the king acquired (stole) the ultimate title to all land in England, through the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, where King Richard II met with Wat Tyler at Smithfield to make promises he would not keep, and where Tyler was killed by the Mayor of London, up to the Diggers' Occupation of St George's Hill in 1649, where they began to cultivate the common land in contravention of the law and to pull down enclosures. But use of the personal collective pronoun 'us' , and the centring of the poem within particular local places, creates a sense of continuity within a class struggle that is more usually framed as a series of disconnected incidents. This allows us both to apprehend the deliberate steps by which the poor are divested of their rights, and by which the rich and powerful naturalise their superiority and dominion. While the poem's trajectory is ultimately despairing, its uncanny temporality calls forth a solidarity with our foresisters and brothers, stretching back into the past. It provides us with a vision of our history that is seldom taught and often hidden from sight.

The language of 'Land Law in England' is authentically Blakean. The final lines of the fourth stanza could equally belong in Winstanley's 'Diggers' Song' or Blake's 'Jerusalem'. This feels vitally important: the poem is proposing poetry and song as an alternative account and way of reading history, a language of reply and resistance to that other, official language of the law.

Salvage

By Bridget Frances Keating

frontier of fog, distance

and depth. the shattered

caress of an oar, a claw.

here, in this conceit

of stricken timbers,

this nursery of tempered

threat.

you have squared the odyssey

inside a bottle; foreshortened

the mariner's monologue into

a drunken text.

silent now. handmaidens all,

coronate damsels, the long

anguilliform thrust of them.

eels, like sullen ladles, spooning

the futureless sea into every

broken mouth from port to

starboard.

no, we are not all equal, but

we are all changed. and we –

aphotic sticklers, the lanterns

and the hatchets – were once

like you.

silent now, and fathom-gilded.

a shoal, a raving multitude. silvered

coin of our own realm.

The title of 'Salvage' by Bridget Frances Keating is an eerie riff on the idea of maritime salvage. In this poem the sea-changed voices of the dead extend a sinister welcome to a group of unspecified addressees numbered amongst the recently drowned. In the opening two stanzas the sunken wreck of a ship is evoked with the macabre theatricality of a haunted mansion in a Victorian Gothic romance: 'This frontier of fog', 'this conceit / of stricken timbers'.

The word 'conceit' in particular creates a sense of fun-house unreality, as if the wreckage were a ride in a theme park, and not a real, historical grave site. In the third stanza the poem breaks into accusatory direct address, with the use of the heavily emphasised 'you' to lay responsibility for the diminishment of the ocean, its dangers, and its tragedies firmly at the feet of those recently arrived interlopers.

The most disturbing and arresting lines of the poem come, I think, in the fourth stanza where eels (presumably pelican eels that can live at depths of up to 3000 metres) are ' spooning / the futureless sea into / every broken mouth from port to starboard'. Invoking the 'broken mouths' reconnects the dreamy unreality of the poem to the literal bodies of the dead, and the idea of 'the futureless sea' suggests both the irrecoverable permanence of the sunken state, and the strange simultaneous time of the ocean, where all disasters occupy the same endless and uncanny 'now'.

In the final two stanzas Keating seeds references that suggest the central theme of the poem is the circular hubris of the rich and powerful. 'We were once like you' say the dead, now transformed into shoals of fish, the 'silvered coin' of their 'own realm'. These signifiers of riches suggest that the speakers of the poem may well be the Titanic's wealthy passengers. Their addressees could be the crew of the Titan, but equally they could be any wealthy seafarer whose arrogance and entitlement proved terminal. The reader is left wondering who or what is 'salvaged', rescued, retrieved or preserved? As all are 'changed' into the members of a more diverse and equal biotariat, perhaps what is salvaged is something like the soul.

Control Town

By Peadar “King Badger” O' Donoghue

See y'after!

After what, Armageddon?

See y'later!

Not if I see you first, Landlord.

Sun Tzu told me what to do,

I'd like to fish your bones

from the waters, lattice them

on the boggy bank that they

might feel their first bite of frost,

form an arched sepulchre for greed.

I see rooks, ravens, hear

foreboding cackles from the trees,

I see shopping trolleys in the pond,

I see the latest politician

hands in someone else's pocket,

I see the discarded needles,

I see a used condom on a dog turd,

I see nobody has any time for anything.

I see record profits are on the up,

bonuses ballooning,

I see half price food half rotten

in aisle twenty, those yellow

labels, if you have too many,

label you at the checkout,

other, poor, unclean, leper.

I see I have to quit this poem.

I see it's gotten me nowhere,

perfect. Let's just sit by the river,

and wait.

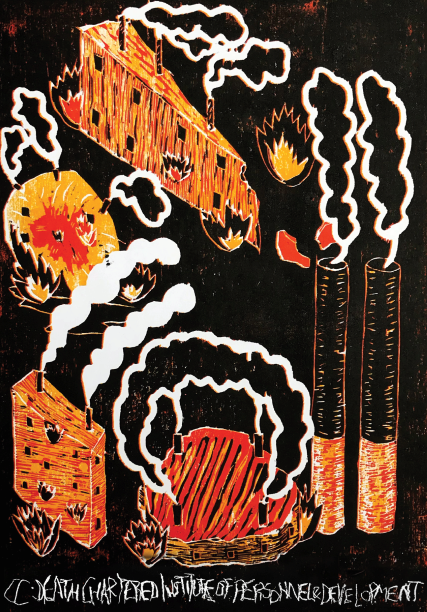

'Control Town' by Peadar O' Donoghue, adopts a similar stock of Gothic-inflected images to Keating, but filters them through a striking tone of despairing rage. In the arresting second stanza, the bones of the wealthy dead are fished from the water, latticed 'on the boggy bank that they / might feel their first bite of frost, / form an arched sepulchre for greed.' While the image is both surreal and macabre, the setting is resolutely ordinary: a choked tributary river in any unlovely working-class town. The driving conceit of the poem is that in death the rich wash up amidst the muck and debris of the world they made, forced at last to inhabit the inequality they helped to create.

There is no “sea-change” in this poem, no possibility of redemption. Instead, the speaker is focused on a recitation of poverty's material traces: 'shopping trolleys in the pond', 'discarded needles', 'a used condom on a dog turd', the 'yellow labels' of half-price food. These mundane, daily reminders of classed life and landscape are interwoven with the insubstantial or concealed nature of extreme wealth: 'record profits', 'bonuses ballooning', 'the latest politician / hands in someone else's pocket'. The dead in O' Donoghue's poem are not ghostly, because wealth and power are already spectral. In this poem their fate – and their punishment – is to become solid bodies, waste amongst the waste.

Again, similar to Keating's piece, the poem has an enigmatic title that might be read a number of ways. The speaker exercises control when they decide to 'just sit by the river, / and wait', but the speaker is also subject to control as a citizen, a worker, and a classed body whose movements, choices, and opportunities are governed by economic inequality. The wealthy dead experience a loss of control – in the sense of autonomy over their own fates – but also they become subject to controlling forces as they are inexorably borne downriver by the tide. It is the indifference of nature, its relentless, motiveless mechanism that ultimately undoes and degrades them, and not the poem's hedged attempts to exert imaginative control over the fates of the rich and powerful. This bleak conclusion has a flip side: the hope that with watchful patience, old orders may be both literally and figuratively swept away.

OceanGate

By Tom Bland

The Playstation controller made Andy Warhol blush:

watching from the moon, Titan, he knew one of the bolts would

go, the pressure imploding, instantly

killing them all, and he knew nothing about science.

The rich are idiots and idiocy is currency

in a world of shock of breaking down

stability for robbing the eruption of

money

that flows out of governments from nonsensical schemes only the

c…………c……u……..u……n…….n……..t……..t…….s

.......................................................................................s

would or

could

devise.

But in nature,

the deep is full of aliens who have a way to break the

unbreakable, those sun-soaked Gucci-wearing humans who

use physics as a game, thinking immortality comes from a

Bitcoin wishing well they control.

KILL THE RICH

MEANS JUST THAT

and Titan drowns the blond haired idol of

capitalism and the ghosts of the Titanic still

screaming

as they endlessly drown under champagne bottles and sharks

endlessly shatter the ice cutouts of the Titan billionaires

in the ice cold dark…

'OceanGate' by Tom Bland is the most explicitly confrontational poem I want to share, but it is also perhaps the strangest, the most camp, and the most absurd. The speaker begins by evoking the discarnate, omnipresent spirit of Andy Warhol, watching the tragedy of the Titan unfold from the nebulous ether, a distant moon base. This choice of detached supernatural observer is not random, Warhol being one of Western culture's best-known commentators on consumer excess, his legend and image now synonymous with the same forces his art sort to engage and critique. The line 'The rich are idiots and idiocy is a currency' might well have issued from Warhol himself as originated with the poem's speaker.

I'm reminded especially of his famous line that “buying is much more American than thinking... and I'm as American as they come”. Here Bland (and Warhol) taps into and dramatises the way the rich recuperate their stupidity and failure as cultural value. The presence of Warhol transforms the catastrophe aboard the Titan into a perverse version of the “15 minutes of fame” – a quote often misattributed to Warhol, describing the phenomena of instant and short-lived celebrity – so that death itself becomes part of the same shallow, endlessly scrolling media circus.

The poem is loosely punctuated, with irregular line breaks that allow the stanzas to bleed in and out of one another. In this way the text performs an uncanny suspension – perhaps in water, perhaps in the gravity vacuum of space – on the page. The effect is dislocating. Phrases and ideas drift and surface, violently surprising the reader, as with the stark, capitalised 'KILL THE RICH / MEANS JUST THAT'.

As with O'Donoghue's poem, Bland is concerned with the waste and detritus of capitalist culture, but he is less interested in the material traces of poverty, than with the lunatic signifiers of obscene wealth: 'Gucci' and 'Bitcoin', 'champagne bottles and sharks'. The poem asks us to consider the sheer absurdity of the death, which, in a saner political and social climate, would not only have been preventable, but unthinkable. It takes a special kind of irrationality to undertake such a journey. It is a symptom of our prevailing sickness, a disease characterised first and foremost by florid delusions of grandeur and invincibility.

However, what I like about Bland's poem is the space it creates to acknowledge our class enmity: to say the unsayable. In this way it is the poetic equivalent of the near-to-the-knuckle memes that did the rounds immediately after news of the sinking broke. It aligns itself with those memes, with all the throwaway and reviled forms of cultural expression, and with sentiments few wish to acknowledge or bother to unravel.