Dennis Broe traces the links between class and the coronavirus, and parallels in cultural works. Plus ca change........

In many ways the rearrangement of life in the wake of the global impact of the Cornoavirus has created a brave new world. And in other ways, the arrangement has reinforced the cowardly old one.

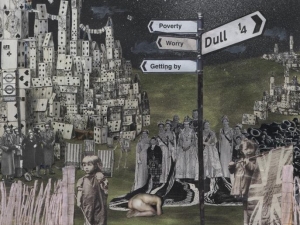

Class differences during widespread global lockdowns and quarantines have in some ways hardened. There is a small minority of a rich class which passes this temporary isolation in comfort, having quickly evacuated the contagion of the city centres for sometimes palatial estates in the countryside. There is a sheltered middle class, many of whom are able to continue to work and earn online, though often at a diminished capacity. And finally there is an unsheltered working class, who must risk their lives in order to earn their daily bread.

Here in Europe and particularly in France these distinctions are as profound as elsewhere, with perhaps a million people fleeing the high-contagion centre of Paris for their country homes, with new middle-class family subscribers flocking to the just opened Disney+ streaming service while cheering on medical workers each night at 8pm from their balconies.

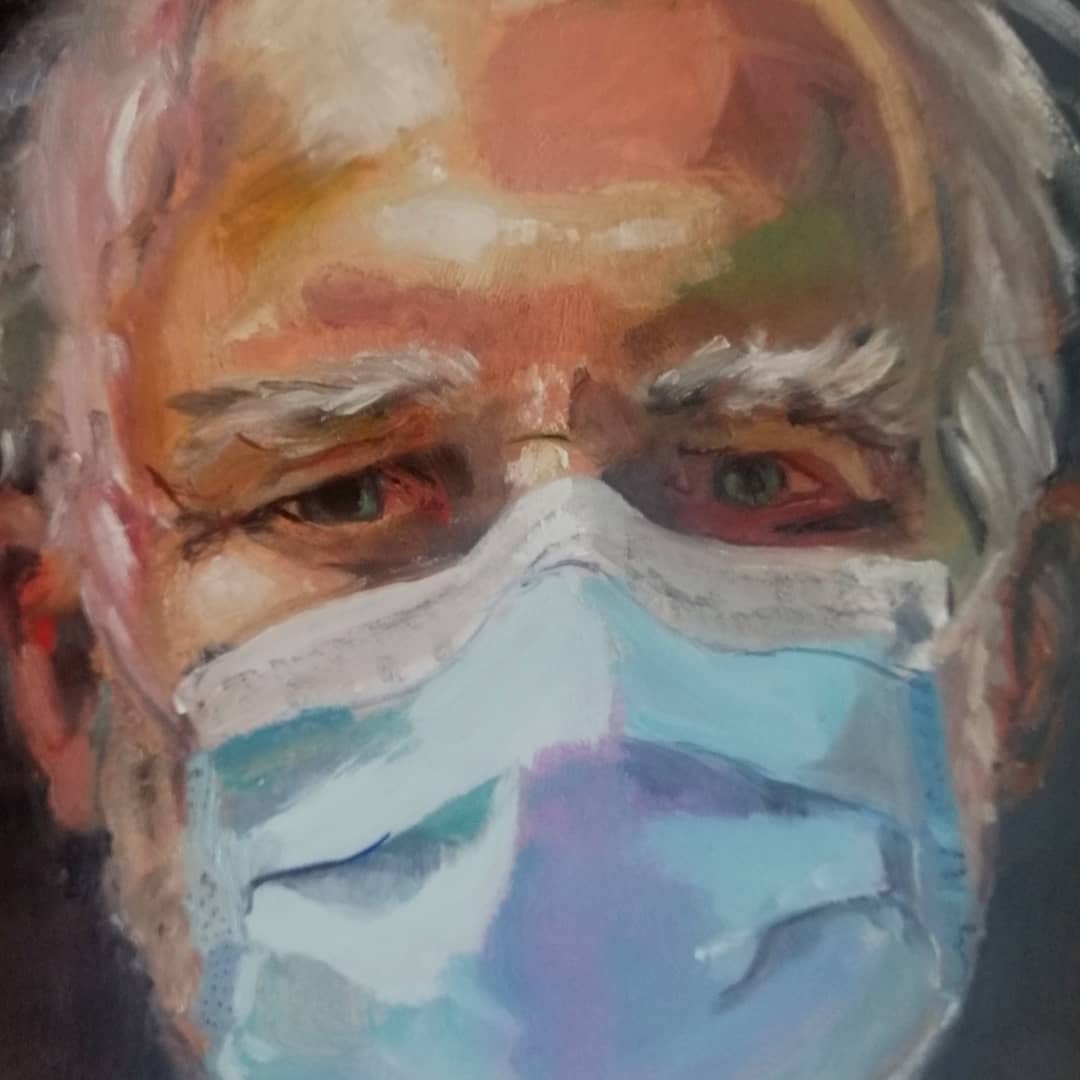

Finally, there are not only working-class nurses but also cashiers, that most unsung group of workers, 90 percent of whom are women and many of whom are from minority ethnic groups. They go to work each day and come home to crowded apartments in the Parisian suburbs, where the police are using the excuse of not having proper quarantine papers to assault these women’s children.

Europe, with its well-developed welfare state, might seem to be better equipped to combat the virus than the U.S., with its hollowed-out state folowing the Reagan-Bush-Clinton neoliberal attack. However, Europe also has experienced wave after wave of shocks and attacks on its social compact. For example, a French cashier noted that while doctors and nurses are being cheered today by both the people and the state, “Only a few months ago,” in the wake of a protest against the cutting of hospital budgets by the Macron government, “They were teargassed for daring to rally in the streets”.

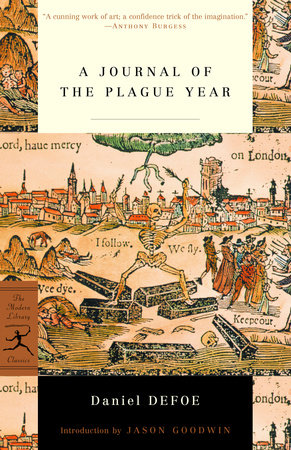

The impact of the virus echoes Daniel Defoe’s historical novel Journal of the Plague Year, written after the deadly assault of an earlier virus on 17th century London, where nearly 15 percent of the city perished. In observing the parallels, one wonders if these are because of the similar nature of each disease or because this new era of greed-take-all capitalism has hurtled us back to the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, where protections for workers were almost nonexistent.

Upper-Class Quarantine: Flight to the Country and Wide Open Spaces

In Defoe’s account when the plague first appeared, “nothing was to be seen but wagons and carts, with goods, women, servants, children…; coaches filled with people of the better sort, and horsemen attending them, and all hurrying away.” His comment on this exodus of the rich from the city to escape the disease is that “they spread it in the country” and had they not fled, the plague would not have “been carried into so many country towns and houses as it was, to the great damage, and indeed to the ruin, of [an] abundance of people.”

Likewise, in France, where there are three million second homes, just before the Macron lockdown, Paris trains and highways were jammed with those exiting the city. After the lockdown the health minister had to beg Parisians to stay at home, rather than fleeing to the rural areas and especially to Normandy which was relatively untouched by the virus. One Brittany resident then saw these urban visitors on the beaches “in cool outfits as if they were on holiday,” adding “Quarantine is always for other people”.

Meanwhile Monaco, surrounded by the European virus epicentre countries of France, Italy and Spain, had (as of recently) only 60 cases total and 4 deaths. This country is the wealthiest in the world, with 30 percent of the population made up of millionaires and with a state that could afford to close the casinos, turn away cruise ships, and furlough for 90 days all its employees.

Elsewhere the French online “faschosphere” was instead quick to blame immigrants for the virus. While others across the world noticed the similarities of the situation with this year’s Academy Award-winner Parasite, with its lower-class family living in a flooded basement, “stealing” internet reception and its upper class, corporate family living in a spacious mansion surrounded by acres of green lawns.

Middle-Class Quarantine: Sheltered in Place and Working Online

The disappearing middle class is sheltered at home, many able to at least pursue some semblance of their business through Zoom, the online meeting app. The company has thrived, going from 10 million to 200 million users as have many online businesses and this has no doubt improved the connectivity of the world. However, as Shoshana Zuboff claims in her monumental work The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, the secret of the internet is that its “evil design aims to exploit human weakness” by creating interfaces that “‘make users emotionally involved in doing something that benefits the designer more than them.’”

Zoom has already been accused of selling data to Facebook and recently hired a Facebook executive as an outsider advisor. The mass use of Zoom is the Holy Grail of selling user data to advertisers. For a long time, there has not been enough data on user’s emotions to match with their words to create more detailed profiles. The Zoom meetings supply that data in abundance, and will increase the quality of data sold or rented that can be used to supply more detailed consumer profiles. As Zuboff says, we grow ever closer to a B.F. Skinner-type “technology of behavior” that would “enable the application of …[surveillance] methods across entire populations.”

It doesn’t have to be this way. Chinese monetization of internet traffic, for example, doesn’t just package data to advertisers. The online service Lizhi creates its revenue stream by offering users the option of buying virtual gifts in which to shower their podcast favorites, as was the case with the Japanese girl group AKB48. Ironically it is China, which does not try to match the US in the efficiency of its consumer surveillance, which is constantly accused of being a thought-control, totalitarian society.

Working-Class Quarantine: Working and At Risk

While wealthy Parisians were fleeing the city, in poor banlieus across the Peripherique such as Saint Denis, where the cashiers, sanitation workers, and health care workers live, there is “an exceptional excess” of deaths from the virus.This is similar to the disproportionate deaths in heavily African-American populated places in the U.S., such as areas of The Bronx and in the immigrant communities of Queens.

Defoe described a similar situation where servants who “were obliged to send up and down the streets for necessaries” contracted the disease. Similarly, restaurant workers along with the delivery service carriers put their lives in danger each day to bring food to those economically above them. Just as in the present pandemic, where in the French supermarkets new recruits from the suburbs abound, so too Defoe detailed a situation where “though the plague was chiefly among the poor, yet were the poor the most venturous and fearless of it, and went about their employment with a sort of brutal courage; ran into any business which they could get employment in, though it was the most hazardous.”

Meanwhile, the police, whose often casual brutality is detailed in this year’s Caesar winner for best French film Les Miserables, have been cited by Human Rights Watch for “unacceptable and illegal” behavior for several beatings of young men from this polyglot area. These victims were accosted because they did or did not have their “attestation,” the legal paper required for leaving the home. The middle class face a fine of 138 euros for not having their papers – the working class face state violence.

In Marseilles, McDonald’s workers, led by the local union, the Force Ouvriere, decided to distribute the company’s food to the poorest districts of that city and to use the closed-down restaurant as a central site for collecting and preparing food. McDonald’s issued a statement opposing the measure.

Similarly, at a Crenshaw McDonald’s in South Central Los Angeles – one of the poorest districts in the US – when the workers staged a spontaneous action demanding they be sent home for a two-week quarantine, the protest was broken up by the police.

Amazon, one of the companies most extravagantly profiting from the quarantine, was temporarily forced to halt its operations in France when a court ruled the company had failed to adequately protect workers. The case was heard because several employees walked off the job, citing a law that allows workers to leave an unsafe workplace and receive full pay. In response, the company criticized the union that brought the case.

What could be more prescient in the light of these protests by a most exploited workforce than Ken Loach’s latest film Sorry We Missed You, about how a delivery driver for an Amazon-type firm is being driven to despair because of the inhuman pressure put on him and his family to produce.

The quarantine also called attention to the importance of seasonal workers in Europe in terms of harvesting crops. In France, with an embargo against non-Europeans coming into the country, 200,000 workers are needed to replace this seasonal workforce to harvest fruit and vegetables in places like the Loire and Alsace to feed the urban population. These workers come from central and eastern Europe as well as from Tunisia and Morocco and most labor under impoverished conditions and leave after the harvest. Jean Renoir’s 1935 film Toni which recounts the tragic life and fate of one of these workers coming across the Pyrenees from Spain is unfortunately still relevant today.

Germany uses 300,000 day-labourers a year to harvest its crops, mostly from Romania, Poland, Ukraine, Bulgaria and Hungary. One of the films that most accurately tracks this discrepancy in income and the disdain of more affluent Germans for these easterners is Western which recounts the prejudice of a group of German workers building a power plant in Bulgaria.

To combat this problem, Portugal granted temporary citizenship status to immigrants while in the US, where the federal government is floating a measure to detain undocumented immigrants indefinitely during “emergencies,” Americans bought almost 2 million guns in March, their own Wild West solution to what they view as the immigrant problem and the anarchy they are afraid will come. The Trump administration seconded this solution, declaring weapons stores to be an essential business that should stay open during the quarantine.

Arundhati Roy’s eloquent description of workers on the roads in India where “our towns and megacities began to extrude their working-class citizens – their migrant workers — like so much unwanted accrual,” and where workers with no other resources had to begin a long walk home to their villages. As they walked, she noted, “some were beaten brutally and humiliated by the police, who were charged with strictly enforcing the curfew” .

Readers might eerily have confused Roy’s description for Defoe’s, since they were so similar. Defoe says:

The constables everywhere were upon their guard not so much, it seems, to stop people passing by as to stop them from taking up their abode in their towns…[because of the “improbable” possibility] that the poor people in London, being distressed and starved for want of work, and want for bread, were up in arms and had raised a tumult, and that they would come out to all the towns round to plunder for bread.

Recurring class tensions have also broken out between states. Before it finally passed a European relief bill, the hardest-hit countries – Spain and Italy – were proposing that the EU issue joint bonds, called Eurobonds or Coronabonds, which would spread the cost of the economic damage caused by the virus among at least the 19 countries of the common currency. The wealthier northern countries, led by Austria, Germany and The Netherlands, refused. It was similar to these countries’ refusal to cancel the debt and instead impose austerity budgets on the countries of the south, after the 2008 crisis.

This disparity on a personal level is well documented in Oleg, one of last year’s best films. The film recounts the story of a butcher from Latvia who emigrates to Brussels, the EU capital and centre of its wealth and affluence, quickly loses his job, and is bullied to join the criminal underground in order to survive. Oleg’s individual path is similar to the national path of countries such as Greece.

Finally, to return to Defoe’s description of the plague, the virulence of that disease hastened the appearances of all kinds of charlatans coming out of the woodwork. Because of fear, working people ran to “fortune tellers, cunning-men and astrologers” and London swarmed with “a wicked generation of pretenders to magic, to the black art… and “to a thousand worse dealings with the devil.”

The difference in this stage of neoliberalism, where the state exists to serve the interests of financial capital – the banks, the real estate and insurance industries who the US government bailed out – is that the con-men are running the show.

Thus Trump, snake-oil salesman and charlatan-in-chief, suggested that people take hydroxychloroquine, an untested drug that could produce fatal heart arrhythmia and that one report claimed Trump had invested in. Trump called the drug a “game changer,” and told his viewers to “Take it. What do you have to lose?”

In Defoe’s time, the King’s court fled the city and allowed lower civil servants to bear the brunt of dealing with the plague. Unfortunately, in our time, the court remains in the White House, and continues the dangerous and deadly process of urging the country to quickly re-open so that the state does not have to subsidize the people, and can continue to ignore worker unemployment and misery.