Jenny Farrell

Jenny Farrell is a lecturer, writer and an Associate Editor of Culture Matters.

Easter Rising 1916: The Wayfarer, by Pádraig Pearse

Jenny Farrell presents the final poem in the series of poems written by the leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916. It is Pádraig Pearse’s “The Wayfarer”. It is Pearse’s last poem, his last statement, written on the eve of his execution in Kilmainham Gaol.

The Wayfarer

by Pádraig Pearse

The beauty of the world hath made me sad,

This beauty that will pass;

Sometimes my heart hath shaken with great joy

To see a leaping squirrel in a tree,

Or a red lady-bird upon a stalk,

Or little rabbits in a field at evening,

Lit by a slanting sun,

Or some green hill where shadows drifted by

Some quiet hill where mountainy man hath sown

And soon would reap; near to the gate of Heaven;

Or children with bare feet upon the sands

Of some ebbed sea, or playing on the streets

Of little towns in Connacht,

Things young and happy.

And then my heart hath told me:

These will pass,

Will pass and change, will die and be no more,

Things bright and green, things young and happy;

And I have gone upon my way

Sorrowful.

A wayfarer is a wanderer across the countryside, akin to a vagabond. It suggests that Pearse views his short life as a time spent wandering, perhaps restless, an observer of life. The fact that he knows he is facing the end of his life, that the world’s beauty “will pass”, has made him “sad”. Explaining this sadness, he states that this beauty has at times been so overwhelming that “my heart hath shaken with great joy”. This physical image, combined with the emotion it describes, is very moving.

The beauty Pearse recalls that has shaken his heart is that of the Irish countryside and people. He evokes this for readers in very vivid and varied images. There is fantastic movement in the “leaping squirrel in a tree” in the mid-distance, to the close-up of “a red lady-bird upon a stalk”, adding a beautiful red touch to the green vegetation. The view pans out further away as the day progresses to evening and evokes “little rabbits in a field” which is lit “by a slanting sun”. The run-on line seems to extend that gloaming.

Next, the eye moves up to take in the solidity of a “green hill” which is not still, but has clouds trailing over it, “shadows drifted by”. In this image of a “quiet hill where mountainy man hath sown / And soon would reap”, nature and humankind merge in the purposeful activity of “mountainy man”, as do present and future blend in “sown / And soon would reap”. Again, movement and process are enacted in a run-on line. It is a ripening Pearse will not live to see. Perhaps the anticipated reaping on the hilltop “near to the gate of Heaven” allowed for some consolation for Pearse. On a more metaphoric level, this sowing and reaping (in the future) also refers to the Rising and that in future, there will be a reaping.

Next, there is a movement from adult to “children”, again suggesting the future. The image is very vivid and tactile: readers can see the children but also feel the sand under their “bare feet”. The fact that the children are barefoot underlines their connectedness to nature. The highly visual “ebbed sea” contains both the present and the future, as the ripples on the wet sand speak of the tide having gone out and turning again. The ebb and tide suggest the everlasting renewal of life and beauty.

In the middle of the line, the image changes away from the seascape to “the streets / Of little towns in Connacht”. Both the sea and the town images expand by enjambment and suggest continuity and perpetuity. Pearse ends these images from the nature and people of Ireland with “Things young and happy.”

The concluding six lines reflect on this evocation of Ireland as a happy and beautiful place and return to the emotion of the poem’s first line “sad”. Pearse’s “heart” has told him that all this beauty will “pass and change, will die and be no more”. The images of the poem however tell the reader while this is true of individual life, there is continuity that outlives individuals. However, Pearse will not be a part of this natural cycle, he will be “gone upon my way”. Pearse poignantly speaks of himself in the past tense at this point, just before he ends the poem on its shortest line – ending his life prematurely on the solitary word “Sorrowful”. The movement we felt in the run-on lines describing vividly the beauty and people of Ireland, are over, the line is cut short, as Pearse’s life was. He was executed the following day, aged thirty-six.

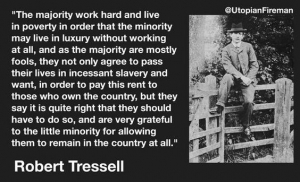

Easter Rising 1916: Die Taube, by Joseph Plunkett

Jenny Farrell presents the third poem written by the poet-leaders of the Irish Easter Rebellion in 1916. It is Joseph Plunkett’s “Die Taube”, written in 1915.

Engagement with German literature was not unusual for the Irish revolutionary poets and leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916. One of the seven signatories of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, Thomas MacDonagh, for example, translated Goethe’s famous “Wanderers Nachtlied” into English. It is an indication that the insurgents of 1916 were internationalists in their outlook.

Joseph Plunkett, the youngest of the signatories – all of whom were executed after the Rising by the British military – wrote the sonnet “Die Taube” on 4 March 1915. This was just days before leaving Ireland on St. Patrick’s Day on a secret mission to Germany. He was to rendezvous with Roger Casement and convey a verbal message from the leadership of the Irish Volunteers. It is therefore a little surprising that Plunkett’s poem suggests he regards Germany at war as abhorrent.

The first clue to reading this poem as a comment on Germany is its title. This is striking, as Plunkett did not speak German. The title draws the reader’s attention to the likelihood that this poem refers to Germany. “Die Taube” means “the dove”, a bird that symbolises love and peace. The fact that Plunkett uses the dove to represent Germany is significant. It immediately suggests something positive. It is pointedly not the German eagle of victory and imperial power.

In addition to this, Plunkett composes a traditional love poem – a Petrarchan sonnet, comprising of the initial octet, rhyming abbaabba, which states the problem, and the concluding sestet rhyming cddcdc, resolving it.

Die Taube

by Joseph Plunkett

To-day when I beheld you all alone

And might have stayed to speak, the watchful love

Leapt up within my heart, — then quick to prove

New strength, the fruit of sorrow you have sown

Sank in my stormy bosom like a stone

Nor dared to rise on flaming plumes above

Passionless winds, till you, O shining dove

Far from the range of wounding words had flown.

The speaker spots a single dove, addressing it familiarly as “you”. He establishes a personal relationship, “might have stayed to speak”, but “the watchful love” that springs up in the speaker’s heart prevents closeness that he would have welcomed otherwise. The entire poem is defined by this ambiguous feeling for Germany, a mood conveyed from the very beginning.

While the bird represents what he feels is good about Germany and therefore his love for it, the dove has sown “the fruit of sorrow”. Given the date, March 1915, nine months into World War I, this can only refer to the hostilities. However, sorrow does not destroy his love; “watchful” merely constrains it. Sorrow over Germany’s war has produced a tangible “fruit” that oppresses the speaker.

The speaker’s sorrow over Germany’s aggression “sinks” in his chest “like a stone”. In the past, Germany had clearly not burdened his heart. The phrase “stormy bosom” suggests turmoil and underlines the double-edged emotion. On the one hand, the speaker has a positive feeling towards Germany, but “sorrow” has gained the upper hand.

His “watchful love” did not dare to ignore the pillars of fire, the rising columns of smoke from burning cities that this war has brought to Europe. It does not dare to rise into the “passionless winds”, the neutral, uninvolved winds of Ireland, until the dove had flown away from the “wounding words” of war propaganda. In contrast to German literature, German war propaganda speaks in “wounding words”. The word “range” connotes a firing range as well as reach. There is no room for loving Germany while it is at war.

Plunkett’s phrase “O shining dove” underlines once more his affection for Germany, something he never loses sight of in the poem. Peace and anything good, worth loving in Germany, symbolised by the dove, has flown far away from Germany.

The poem’s concluding sestet comments on this predicament. The sestet divides into a quatrain and a concluding couplet:

Far have you flown, and blows of battle cease

To drape the skies in tapestries of blood,

Now sinks within my heart the heaving flood

And Love’s long-fluttering pinions I release,

Bidding them not return till blooms the bud

On olive branch, borne by the bird of peace.

The dove has flown to a place where skies are free from the blood of war - to Ireland, where the speaker resides. The speaker renews the image of a heaviness in his heart: “heaving flood” is a very physical image, as palpable as the fruit of sorrow, but even more forceful. A different kind of sensation is evoked, a repeated welling-up. The speaker lets go of the dove, releasing it. The beautiful, tactile adjective “long-fluttering” wings once more emphasises a long love for Germany.

In keeping with the sonnet form, the final two lines arrive at the conclusion. The dove is not to return until it brings peace. The image is both tangible and vivid: “till blooms the bud / On olive branch”. The line break enacts a momentary delay and builds up to the emphasis on “peace”, the last word of the poem. What the speaker loved about Germany is no longer there. He hopes it will return some day, but it cannot come back unless it brings peace. There can be no love on the basis of war.

This reading of Joseph Plunkett’s “Die Taube” reveals his very ambiguous feelings towards Germany at war, the place he was about to travel to. While using a traditional love poem form ironically, he makes his position abundantly clear that he has no illusions about the militarist nature of Germany at that time. There is no suggestion that fighting in this war is heroic. Plunkett was going on a peace mission of a different kind: one that he hoped would bring Ireland her independence from both King and Kaiser.

Easter Rising 1916: The Man Upright, by Thomas MacDonagh

Jenny Farrell presents the second of the four poems written by leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising, the first anti-imperialist uprising in Europe. Here is Thomas MacDonagh’s “The Man Upright”, written in 1911/12, which reveals MacDonagh’s view of the crippling effect of colonialism.

The Man Upright

by Thomas MacDonagh

I once spent an evening in a village

Where the people are all taken up with tillage,

Or do some business in a small way

Among themselves, and all the day

Go crooked, doubled to half their size,

Both working and loafing, with their eyes

Stuck in the ground or in a board, -

For some of them tailor, and some of them hoard

Pence in a till in their little shops,

And some of them shoe-soles - they get the tops

Ready-made from England, and they die cobblers -

All bent up double, a village of hobblers

And slouchers and squatters, whether they straggle

Up and down, or bend to haggle

Over a counter, or bend at a plough,

Or to dig with a spade, or to milk a cow,

Or to shove the goose-iron stiffly along

The stuff on the sleeve-board, or lace the fong

In the boot on the last, or to draw the wax-end

Tight cross-ways - and so to make or to mend

What will soon be worn out by the crooked people.

The only thing straight in the place was the steeple,

I thought at first. I was wrong in that;

For there past the window at which I sat

Watching the crooked little men

Go slouching, and with the gait of a hen

An odd little woman go pattering past,

And the cobbler crouching over his last

In the window opposite, and next door

The tailor squatting inside on the floor -

While I watched them, as I have said before,

And thought that only the steeple was straight,

There came a man of a different gait -

A man who neither slouched nor pattered,

But planted his steps as if each step mattered;

Yet walked down the middle of the street

Not like a policeman on his beat,

But like a man with nothing to do

Except walk straight upright like me and you.

This is a very easy, entertaining poem with a serious point. It begins almost like a limerick, sets jocular tone, rhymes aabb etc. It is an observation by an outsider: “I once spent an evening in a village”. The people in this village work in farming or small business. All day long, they walk crooked, doubled over “to half their size”. Increasingly we get the impression of colonial subjects in Ireland, who do not have the confidence to stand upright, nor, it seems, have they a vision of where their lives are going: “with their eyes/ Stuck in the ground”. Those who work in small trades receive their materials from England, rather than Ireland, increasing their economic dependence. Cobblers, for example, “get the tops / Ready-made from England”. MacDonagh’s description of the villagers is uncomplimentary to say the least: “a village of hobblers / And slouchers and squatters, whether they straggle / Up and down, or bend to haggle / Over a counter, or bend at a plough,” … He depicts them as people who are utterly crippled in their humanity. No matter what they do for work, they are obliged to bend down. Rather than work expressing their humanity, it acts as their master.

Midway through the poem, we hear that there is something visibly straight in this village of the damned: “The only thing straight in the place was the steeple”. This may well refer to the additional control by the Church over these people. The contrast is very striking to the humbleness and lack of confidence described up to this point. The next line extends this initial surprise into something more significant. It contains the poem’s only caesura and turns the whole flow of the poem around: “I thought at first. I was wrong in that”. The reader’s expectation is heightened as the speaker for the sake of emphasis returns for a moment to the crooked villagers and then exclaims: “There came a man of a different gait - / A man who neither slouched nor pattered”. In fact, this man is said to be “like a man with nothing to do / Except walk straight upright like me and you.” Walking upright is the main purpose of this man’s life - like struggling for an independent socialist republic, it's the obvious and straightforward thing to do.

Following the defeat of the Rising, Thomas MacDonagh was court martialed and executed by firing squad on 3 May 1916, aged just thirty-eight.

Easter Rising 1916: Mise Éire / I am Ireland by Pádraig Pearse

Jenny Farrell introduces a short series of poems and commentary to mark the Easter Rising 1916

Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Ireland will for the first time in its history be unable to publicly remember the Easter Rising of 1916, its aspirations for an independent socialist Republic, and its heroic leaders.

As a number of these leaders were poets and writers, this is an opportunity to look at one or two of their poems, to see what kind of people they were, how their emotions live on in the poetry and how it speaks to us today.

For this Easter, I am going to look at four poems by three of the leaders, Pádraig Pearse, who wrote the 1916 Proclamation of the Republic, and his comrades and signatories Thomas MacDonagh and James Plunkett.

We’ll begin with the most famous poem, Mise Éire/ I am Ireland, written by Pádraig Pearse in 1912.

Mise Éire / I am Ireland

by Pádraig Pearse

I am Ireland:

I am older than the old woman of Beara.

Great my glory:

I who bore Cuchulainn, the brave.

Great my shame:

My own children who sold their mother.

Great my pain:

My irreconcilable enemy who harrasses me continually…

Great my sorrow

That crowd, in whom I placed my trust, died.

I am Ireland:

I am lonelier than the old woman of Beara.

Pádraig Pearse wrote this poem in Irish. The title is a bold statement of identification with Ireland. At the same time, it is Ireland herself speaking.

The “old woman”, in the original “cailleach Bheara”, is a mysterious figure in Irish myth and folklore. Cailleach in Old Gaelic means ‘veiled one’, suggesting ancient origins of the wise-women or female Druids of pre-Christian, possibly pre-Celtic times. The Lament of the Old Woman of Beare is regarded one of finest surviving examples of early Irish verse. She was famed to be mother and foster mother to at least 50 children who went on to found tribes. Pearse makes that connection and echoes the tone of this 9th c lament – speaking as a female ‘I’, like in the Lament – only this I is older, she is Ireland.

The tone is reminiscent of an incantation: “Great is my” will be repeated four time. The first time Ireland refers to her “glory”, because she gave birth to Cuchulainn, champion of the early 1st c Ulster Cycle, celtic foundations myths about the heroes of the kingdom of Ulster. These legends had been all but forgotten by the 7th c when bard, Sechan Torpeist, revived them.

Ireland is placed in the context of a wondrous past that is past – of having once had a flowering and vibrant culture. An example of this culture is the great saga of Cú Chulainn. Pearse makes a statement which contradicts the British colonial narrative of Irish cultural inferiority; Irish literature is the oldest vernacular literature in Western Europe.

The rhetorically powerful repetition “Great my” next presents the polar opposite to “glory” – “shame”. Ireland’s glory lies in the past, conflicting with her “shame”, referring to more recent times. The contrast is continued in the parallel between Cuchulainn and “My own children who sold their mother”. The verb “sold” underlines that these are not ancient but modern times. This contrast highlights the shameful reality of Pearse’s time, of a nation on its knees, ashamed of itself and accepting its conquerors’ narrative.

The children who sold their mother refers to the new Irish establishment, which accepted its inferior place in the British scheme of things – the people now known as Redmondites. They strove for Catholic rights, not Irish nationhood. They wanted the Catholic middle class to have an equal access to power and influence, but within the safe harbour of Britishness.

The third repetition “Great my” – expands on “shame”, intensifying it. While shame is opposite of pride/glory, it hurts emotionally, pain hurts physically. The enemy, with whom no peace is possible, dominates and inflicts injury in this woman’s own place

The final repetition of “Great my” refers to “sorrow”, which follows this pain. The old woman/ Ireland has suffered betrayal by “That crowd, in whom I placed my trust”: The Redmondite politicians who took over from Parnell, who pretended to be the champions of national freedom but worked to keep Ireland part of the Empire.

The speaker finally returns to opening statement, with a change from “older” to “lonelier”, resulting from her experience, as revealed this poem. The cailleach Bhéara ended her days in loneliness because she was left alone, lamenting the disappearance of her glorious past. In Pearse’s poem Ireland had no one to turn to after her leaders (Redmond’s crowd) betrayed her. However, the fact that the Pearse wrote this lament on behalf of Ireland is a call for new leaders to take on the cause of Ireland.

The deep and realistic humanism of Raphael

Jenny Farrell presents the life and some of the work of Raphael, who died 500 years ago

The great Italian painter and architect, Raphael, died on April 6, 1520. He lived at the time of the Italian High Renaissance, one of the most progressive periods of history. As Engels put it:

It was the greatest progressive revolution that mankind has so far experienced, a time which called for giants and produced giants – giants in power of thought, passion, and character, in universality and learning.

The High Renaissance

Raphael was one of the three greatest masters of the High Renaissance, the brief period between 1500 and 1530 which was the heyday of early capitalist art in Italy. First beginnings of capitalist production arose in the 14th and 15th centuries in Florence and Genoa; artisanship and banking flourished in the cities of northern and central Italy until the 15th century. Wealth and luxury expanded, and the power-seeking ruling classes gave the arts great representative and decorative tasks, to express and legitimise their own importance.

The High Renaissance witnessed a highpoint for the visual arts. Even in the turmoil of the Italian wars from 1494 to 1559, when French and Spanish troops ravaged the country and the economy, the arts did not lose their importance. Florence had developed into a cultural metropolis under the rule of the Medici family, from 1450 to 1494. In the first decade of the 16th century, Rome took over this role.

By the time Renaissance art reached its peak, Italy’s economic decline had begun, the Italian states were facing economic and political difficulties, and the Italian bourgeoisie withdrew from banking and usury, investing their capital in land. This ultimately led to a revival of feudal conditions in Italy. The successors to the powerful early capitalist dynasty and patrons of the arts, the Medici, made themselves dukes of Tuscany, as absolutism replaced republican control.

However, the progressive thinkers and artists of the 16th century all remained committed to the defence of the people and even democratised the philosophy of humanism, which had originally been limited to a small group of intellectuals. Their works appeared in the vernacular and emphasised national and democratic ideals. This made the Italian High Renaissance a significant and unparalleled event.

Raphael

Raphael was born in Urbino in 1483. At the age of 17, he joined the Perugino workshop. Here he first learnt to give expression to psychological delicacy, which arises with the Renaissance discovery of human beings as this-worldly individuals.

From 1504 to 1508, Raphael worked in Florence. When Raphael arrived in Florence he was only 21 years of age, and yet he was quickly regarded one of the giants of the High Renaissance, along with Michelangelo, aged 29 at the time, and Leonardo da Vinci, who was 52 years old.

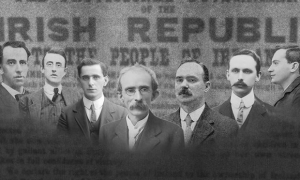

Sistine Chapel ceiling, by Michelangelo, 1508-1512

As Raphael’s fame spread, Pope Julius II called him to Rome. Michelangelo was painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel at the time. Leonardo da Vinci was at the height of his creativity. Leonardo and Michelangelo had both studied the anatomy of the human body and its movements, and created their compositions from the action and interaction of living bodies and moving faces.

So Raphael went to Rome at the behest of Julius II, nicknamed the Warrior Pope or the Fearsome Pope of the Rovere family. During the Renaissance, the popes were not only ecclesiastical leaders, but also princes of Roman territories.

Julius participated personally in wars and famously stated he preferred the smell of gunpowder to that of incense. He sought to construct magnificent buildings with monumental decorations, as witness to his power and that of the Church. In the Vatican, Julius II brought in artists to paint rooms and other spaces. In 1509, he commissioned Raphael to decorate some rooms, with monumental frescoes on the ceilings and walls. The most famous of these is the Stanza della segnatura (Signature room).

The School of Athens

Set in a great architectural illusion, the “School of Athens” portrays an entirely male ancient world. Curiously, Christian thinkers do not appear, although it is the Vatican. Although many of the figures lived at different times, they are shown together as part of the Athens school.

The School of Athens, by Raphael, 1509

The two main figures in the work, centred under the archway, in the fresco’s vanishing point, represent two schools: Plato, to whom Raphael gives Leonardo’s features, pointing upwards into the realm of ideas, his student Aristotle gesturing to earthly, physical experience. Each of these philosophers holds his book representing his thinking: Plato holds the “Timaeus”, Aristotle his “Ethics”, both in modern binding of Raphael’s time. Their clothes support their stances: Plato is dressed in the colours of air and fire, Aristotle is in those of earth and water.

The painting divides into two halves along these lines. Philosophers, poets and thinkers on Plato’s side, and physicists, scientists and more empirical thinkers gather on Aristotle’s side. On the left, along with Plato, you can see the Greek philosopher Socrates, talking to Athenians.

Socrates famously expounded his philosophical thinking in conversation with people. He was Plato’s teacher. Alexander the Great, king of Macedonia and pupil of Aristotle, is shown listening attentively to Socrates, who is emphasizing arguments on his fingers. In the foreground, Pythagoras, who pre-dates Socrates, sits with a book and an inkwell, surrounded by students. Epicurus, on the other hand, lived after the other philosophers, is the chubby fellow with a crown of vine leaves. He taught that happiness lies in the pursuit of pleasures arising from freedom from fear and absence of pain.

Diogenes the Cynic, who lived off charity, lies happily on the steps with his drinking bowl, his body pointing to the Aristotle side of the painting. On the right in front, appears Euclid, explaining the laws of geometry with a compass. He is demonstrating the measurability of actual things – concrete theorems with exact answers show why he represents Aristotle’s side. His face is modelled on the great architect Bramante, whose design of St. Peter’s was based on a geometrical pattern of circles and squares.

Raphael was entrusted with the completion of this building after Bramante’s death in 1514, the largest ecclesiastical construction project in the West. Interestingly, the pope permitted German Dominicans to sell indulgences to pay for it, which ultimately helped spark the Protestant Reformation in 1517.

The classical statues on either side of the picture also reinforce the two philosophies. On Plato’s side we have Apollo, the god of the sun, poetry and music. On Aristotle’s side, Athena is the goddess of wisdom, medicine, commerce, handicrafts, the arts in general, and later on, war – perhaps more earthly concerns.

The foreground is less peopled than the rest of the painting, making way for the two philosophers. Two figures are, however, placed here in isolation, while the others engage with groups of people. They are Diogenes and Heraclitus, the latter being the first great European dialectician, wearing the clothes of a stonemason. Interestingly, Raphael appears to have given him Michelangelo’s features.

The great mathematician and astronomer Ptolemy, wearing a yellow robe, holds a terrestrial globe in his hand, facing the Persian Zoroaster showing a celestial sphere. Interestingly, the young man standing amongst these scientists, and the only figure looking directly at the viewer, is Raphael himself. Incorporating this self-portrait into a work of such intellectual history was a confident stance for the artist. Placing himself, and the portraits of some of his contemporary artists in this fresco along with the greatest thinkers in European history, elevates the significance of the arts in the High Renaissance.

The Sistine Madonna

Raphael is one of the great discoverers of the feminine in painting; his lifelong preoccupation with the Madonna that guided him to this subject, the love between human mother and child, indeed one might say that ancient mother cults live on in this theme.

Around 1512/ 1513 he created his three large Marian altars, among them the “Sistine Madonna”. Alongside the frescos of the Vatican, the “Sistine Madonna” (1512/1513) is considered Raphael’s main work.

The Sistine Madonna, Raphael, c.1512

In this work, Raphael continues his effort to make Mary appear more maternal and human. The model is assumed to be Margherita Luti, the daughter of a Roman baker named Francesco. It’s believed that Margherita was Raphael’s partner for the last twelve years of his life.

Her person expresses a depth that cannot be found in any other of Raphael’s Madonnas. She comes barefoot, carrying her child like a peasant woman. Her left arm, his right arm and her flowing veil form a protective circle around the child. The child echoes his mother’s apprehensive expression, as he snuggles up to her. It is a profoundly human and this-worldly depiction.

The two angels at the bottom of the painting appear to have escaped from the heavenly hosts in the background but also look exceedingly human. The very original host of ghostly angels’ faces crowding the background add to the forward drive of the Madonna, who seems to be walking right out of the painting.

Raphael died on his birthday, aged just 37 years on April 6, 1520 after eight days of illness from pneumonia, and was buried the following day in the Pantheon.

Chopin and the revolutionary inspiration of his Polonaise in A flat major

Jenny Farrell discusses Fryderyk Chopin and the revolutionary inspiration, force and vigour of his Polonaise in A flat major

Fryderyk Chopin was born on 22 February 1810 in Żelazowa Wola near Warsaw, to a Polish mother and a French father. He grew up in Warsaw but left Poland in 1831, shortly before the Polish popular uprising against the tsarist oppressors. He moved to Paris, where he lived until his death aged only 39 on 17 October 1849. In Paris, he made friends with some of the most outstanding progressive figures of his time: with the great Frenchwoman George Sand, who became his lover, the Hungarian nationalist and composer Franz Liszt, the revolutionary French painter Eugène Delacroix, the great Polish poet and political activist Adam Mickiewicz, the German exiled poet Heinrich Heine, and others.

Chopin always remained close to Poland. During the 1830s and 1840s Europe witnessed political repression, unrest, and conservatism. In this atmosphere the great significance of national cultures in shaping national consciousness and the struggle for independence became increasingly important and apparent. This growing national awareness was also reflected in the arts and in music.

Polish music was no exception. The Polish people, who suffered triple occupation by Prussia, Russia and Austria, who were deprived of their independence, who suffered terribly under the pressure of the Holy Alliance, whose national culture was being suppressed – this people proved through its art that it was alive and fighting. The genius of a Mickiewicz in poetry, the genius of a Chopin in music, reflect this struggle in their art.

Chopin wrote mainly music for the piano. He chose smaller forms to express the struggle and aspirations of his people, frequently using Polish peasant dance forms such as mazurkas and polonaises. He revived the music of the whole nation. The folk music of Poland informed his harmonic language. Chopin’s music defined a tradition, not only in Poland but has contributed to our musical heritage internationally. It is an assertion of Polish resistance, something that all independence-loving people can identify with.

Polonaise in A flat major (1842)

Chopin created 17 polonaises in total, his first when he was aged seven, and composed seven of these after he left Poland. The later compositions opened a new chapter in the history of the genre in the direction of the “epic-dramatic poem”. Each of these seven mature, dramatic works has its own distinctive shape, style and expression. The last three compositions are grand dance poems. Chopin’s late Polonaise in A flat major (Opus 53, Héroïque) is written in a heroic tone. On hearing it, George Sand wrote in one of her letters “The inspiration! The force! The vigour! There is no doubt that such a spirit must be present in the French Revolution. From now on this polonaise should be a symbol, a heroic symbol”.

Its stormy octaves in the middle section have suggested to some commentators the image of attacking hussars, to others an attacking cavalcade. Some have called it the “secret national anthem” of Poland. However, Chopin did not leave a ‘story’ to go with this polonaise. I think it is perhaps best understood as the triumph of the Polish dance. The theme is confident and dance-like. It goes through various developments and returns jubilant, proud and heroic in a clearly victorious coda. And it is in this context of the triumphant people that Sand’s comment makes complete sense.

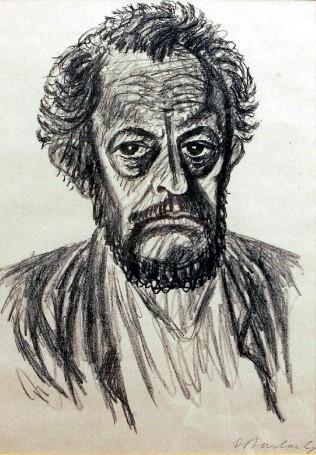

A deep and compassionate humanism: the 150th anniversary of Ernst Barlach

Jenny Farrell presents the life and work of Ernst Barlach, born 150 years ago

Ernst Barlach was born near Hamburg on 2 January 1870. He was the most important German sculptor of the 20th century. Brecht said about his work: “His genius, meaning, ingenious craftsmanship, beauty without embellishment, stature without over-stretching, harmony without smoothness, vitality without brutality make Barlach's sculptures masterpieces”.

Barlach was educated in Hamburg and Dresden, also studying in Paris. A trip to Russia in 1906 was a decisive moment in his artistic development. The sense of community among the ordinary people there impressed him deeply, but also their sadness, and a threatening silence after the failed revolution of 1905.

In 1910, Barlach settled in the northern town of Güstrow. Systematic slander of his art started even before Hitler took power. In Güstrow, Barlach created much of his work, removed and partly destroyed by fascists after 1933. In 1937, the commission for “degenerate art” confiscated his works exhibited in German museums, including the memorial for the victims of war in Magdeburg Cathedral. He wrote to his brother Hans following this event: “I will not be able to work for the foreseeable future ... I won't go abroad, I feel like an emigrant in my homeland - and worse than a real one, because all the wolves are howling at me and behind me.” In this year before his death, he created masterpieces such as “Freezing old Woman” and “Laughing old Woman”, testimonies to his courage, his terror and his humour. Barlach died on 24 October 1938 and was buried in the town of his childhood, Ratzeburg.

Barlach's independent sculptural style is sparse, weighty, expressing both serenity and tension. His masterful woodcuts strongly influenced Käthe Kollwitz and Gerhard Marcks as well as sculptors of younger generations.

Barlach's lithograph “Mass Grave” of 1915 was not deemed safe for printing until much later, in a very small edition. His lithograph “From a Modern Dance of Death” depicts the murderous grimace of war. His 1919 large-format woodcuts express social degradation as a direct result of the dehumanisation caused by war. They include “Death of a child”, “Robbers of the Cross and Coffin”, “Good Samaritans”. These works moved Käthe Kollwitz so deeply that she tried her hand at woodcutting, creating her famous memorial sheet for Karl Liebknecht.

In January 1952, Brecht recorded his “Notes on the Barlach Exhibition” at the German Academy of Arts.

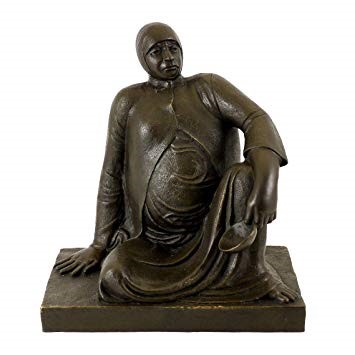

Brecht wrote about “Russian Beggar Woman with a Bowl” (1906): “A powerful person with hard confidence, from whom no thanks for alms may be expected. She seems immune to the hypocritical assertions of a corrupt society that one can achieve something by diligence and making oneself useful.”

In “The Melon Cutter” (Bronze, 1907), Brecht praises “a work which created an eater from the people with great sensual power. He has seated himself exactly as it is best suited for this very activity, and he does not lose himself in his work.”

Brecht liked this wood carving of “Three singing women” (1911) “because the combination of power and singing is pleasant to me.”

Song is represented differently in this sculpture “The Singing Man” (Bronze, 1928). Brecht finds this man “bold, in a free posture, clearly working on his singing. He sings alone, but apparently has an audience. Barlach's humour desires him to be a little vain, but no more than is compatible with the practice of art.”

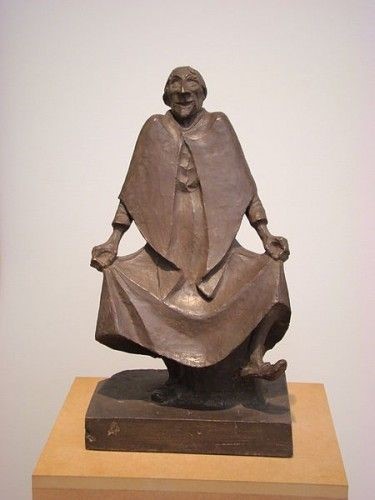

In “Dancing old Woman” (Tinted Plaster, 1920) Brecht praises the “humour, which is extremely rare in German sculpture. The grandeur with which the old woman lifts her skirt to dare another little dance! Her gaze is directed upwards: she delves in her memory for the right step.”

The Kiss groups 1 and 2 (bronze, 1921) are “of great interest” to Brecht “because the sculptor ... achieved a greater intimacy by roughening the material, i.e. by actually coarsening it. The work is a pleasing departure from the sweet, genderless Cupid and Psyche figurines in the drawing rooms of the petty bourgeoisie.”

The year they were made is particularly significant for the sculptures from 1933 onwards. There is “The Book Reader” (Bronze, 1936). A man sits bent over, holding a book in his heavy hands. Brecht said: “He reads with curiosity, confidently, critically. He is clearly looking for solutions to urgent problems in the book. . . I like “The Book Reader” better than Rodin's famous “Thinker”, which only shows the difficulty of thinking. Barlach's sculpture is more realistic, more concrete, not symbolic.”

“Freezing old woman” (Teak, 1937) interests Brecht because this crouching “maid or small farming woman, so visibly physically and mentally abandoned by society” could not “protect her hands from the cold”. Brecht continues, “It is as if her job is to freeze, and she shows no anger. But the sculptor shows anger, far more anger than pity”.

In his commentary on “Seated old Woman” (Bronze, 1933) Brecht refers to how “masterfully the clothing is designed”. “One tiny detail makes it completely realistic: the woollen scarf... The old woman sits upright, she is thinking. ... I can imagine a worker nudging Barlach’s old woman with his elbow: Take power! You have everything that you need.”

From 1937 comes “Laughing old Woman” (wood). Brecht enjoys its irresistible cheerfulness and points out that this was the year in which Barlach's works were banned from German museums as degenerate. “Her laughter is like singing, it has loosened the entire body, making it almost look young.”

All these sculptures point in a realistic way to the essential humanity in people and express Barlach's love of people, his deep and compassionate humanism. Brecht concludes, “Barlach writes: 'It is probably the case that the artist knows more than he can say. But perhaps it is so that Barlach can say more than he knows.”

Waiting for Godot

Jenny Farrell discusses Beckett's Waiting for Godot and its message to us today

Great Carthage waged three wars. It was still powerful after the first, habitable still after the second. Gone without trace after the third. - Brecht, 1951 (transl. JF)

Samuel Beckett died thirty years ago, on 22 December 1989. He received the Nobel Prize for literature, 50 years ago, in 1969. Arguably, Beckett’s most famous play is Waiting for Godot. Typically, when presenting this play today, its comic content is emphasised, as is its ‘absurdist’ label, suggesting that life is meaningless.

Beckett had moved permanently to France in the late 1920s. After the outbreak of WWII, Beckett remained in Paris, where he joined the Resistance following the Nazi invasion of France. He only barely escaped the Gestapo on a number of occasions, and after members of Beckett's underground resistance group were arrested, he was forced to flee to the unoccupied zone in the South of France, where he continued to support the Resistance.

From 1947 on, Beckett wrote primarily in French. Waiting for Godot, written in 1948, is no exception. The Second World War was just over, and this is a supremely important factor in understanding the play, and one that is rarely recognised.

Although this is not specifically stated, Beckett’s play effectively presents the audience with a post-nuclear-war scene. The stage is practically empty except for a country road and a bare tree. In this landscape, two characters, Vladimir (Didi) and Estragon (Gogo), just about exist. These two men struggle to perform the most elementary actions like taking off a shoe. They sleep rough and are regularly beaten up by gangs at night. This is so commonplace that they barely comment on it. The human experience is reduced to simply staying alive and performing, with effort, the simplest actions. Homo sapiens, it seems, has all but been stripped of the ‘sapiens’ part. The characters even find it difficult to stand upright.

In 1948, after World War II and the nuclear carnage of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, people have almost come to the end of their humanity and any positive human experience. The tree of life is almost barren; in this play, it becomes a possible prop on which to hang oneself.

Traditionally, plays begin with an exposition leading to action, or indeed in the middle of an action. In Waiting for Godot, there is no prospect for action. The first utterance of the play is “Nothing to be done.” The entire play presents us with the two main characters, Didi and Gogo doing nothing and waiting in vain. They have replaced the protagonists of the past – those who struggle against adversity, injustice or attempt to create a meaningful life. Narratives that were once useful to endorse human goodness have all been stripped of their meaning, including a clearly vain hope for God(ot) to arrive. In fact, waiting for God(ot) prevents any movement out of this state.

Past certainties are undermined; theatre as we know it has come to an end. The idea of human perfectibility is finished. The parables of the Bible too are useless. Didi and Gogo hardly remember them. When a boy appears to tell them that Godot is not coming today, Estragon refers to himself as Adam. Humankind has become what Shakespeare’s King Lear refers to when he speaks of the most destitute: a “poor, bare, forked animal”.

Our two protagonists are not defined in class terms. They seem to be vagrants. However, they are not completely alone in the world. Not only do we hear of random violence against them, at two points in the play, once in each act, Pozzo passes through with a slave (Lucky) whom he has tied to a rope and treats like an animal. Pozzo is a nod to the existence of a ‘master’ class, one who has money and still holds slaves. Lucky seems like a version of Prospero’s Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, the indigenous native of the island, kept ignorant and enslaved by Prospero. In the one, all but incomprehensible, statement made by Lucky, he says: “Given the existence . . .of a personal God ... outside (of) time . . . who . . . loves us dearly . . . and suffers . . .with those who . . . are plunged in torment . . . it is established beyond all doubt . . . that man . . . for reasons unknown . . . (has left) labours abandoned left unfinished . . . abandoned unfinished . . .” In other words, God/ man has left labours unfinished.

When Pozzo sees Gogo and Didi, he comments: “You are human beings none the less. … Of the same species as myself. … Made in God’s image!” Any aspiration to godlike form and intellect has been annulled, or perhaps the reverse applies: God is this.

When Pozzo and Lucky appear again in Act II, Pozzo has gone blind and Lucky mute. This is a downward spiral in human development. Thinking is an effort. On one occasion, Didi and Gogo contemplate suicide by hanging from the bare tree (of life?). One reason, they do not do this is that one of them may remain alive and therefore alone. That is a fate worse than death. “I remain in the dark.” This gives some hope. Two characters are after all a small community and they do help each other survive.

Apart from this dependency on another human being, there is another example of common humanity. When Pozzo asks Gogo and Didi for help to get to his feet, they respond to this (after asking for money) “it is not everyday that we are needed.” This profound statement acknowledges that Pozzo’s call for help is addressed to “all of mankind,” and “at this place, at this moment of time, all mankind is us, whether we like it or not.” Ironically, all four men end up on the ground and their cries for help go unheeded. Standing upright has become impossible. Purposeful labour and action no longer define us.

Beckett’s play is of immediate relevance to the world today. Like Brecht, he warns of the ultimate destruction of humanity. However, Beckett leaves us with a sense of that all is not lost. His characters still help each other at times of need, they still have that humanity. The tree bears a few leaves at the end of the play, it is not dead. Yet that hope is tenuous. Will the characters be strong enough to move on? Beckett does not give his audience much hope. There is no progress in the play. All we can do is take this message to heart and change the world.

From the dystopian chaos of the free market to the solidarity of co-operative communism: the Maddaddam trilogy

Jenny Farrell discusses Margaret Atwood’s Maddaddam trilogy

Margaret Atwood, who turns 80 in November 2019, has written several novels that explore dystopian situations or circumstances where people are subjected to control and violence. Arguably, the most famous of these is The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). However, what distinguishes Atwood’s work is that people resist such coercion, not just in individual acts but most successfully as part of a secret group or illicit organization. This might be considered a leitmotif of her work. We encounter such resistance not only in The Handmaid’s Tale, but also elsewhere, for example in the deeply disturbing The Heart Goes Last (2015), or in her contemporary take on Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Hag-Seed (2016).

Oscar Wilde, in The Soul of Man Under Socialism, had this to say about hopes for a positive future:

A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail. Progress is the realisation of Utopias.

Utopia, according to Wilde, is the hope of a better possible life, one where humanity will feel at home. Thinking about what will define such an ideal, and that progress towards it, occupied writers from Thomas More to William Morris. With the Industrial Revolution and the appearance of more hidden forces at work in society at the beginning of the 19th century, the arts increasingly reflected the experience of horror, the experience of extreme violence over people and nature. The old, visible powers of feudal society (God, king, law) enter into an alliance with the invisible powers of capital, and everyday life becomes a world in which the ghostly terror of an anonymous, dominating and oppressive power is omnipresent, and which can break out at any time. Examples of such horror are the work of E.T.A. Hoffmann, Goya’s Caprichos and Desastres de la Guerra, and Schubert’s Winterreise. Towards the end of the 19th century, further manifestations are Stoker’s Dracula and Munch’s The Scream.

These visions of horror become the dystopias of the 20th and 21st centuries, many leaving little hope for liberation. Continuing wars with their displacement of people, the ever increasing anonymity of domination and accompanying loss of control, as well as environmental disaster are all valid factors feeding into this pessimism.

Margaret Atwood’s Maddaddam trilogy imagines an all but post-human world. She explores a world where the free market has led to global anarchy. A technocracy of enormous corporations has destroyed national governments, communities, the ecosystem and almost extinguished life on the planet. Apart from a very few humans, there are left genetically engineered animals such as pigoons, wolvogs and rakunks, and artificially created creatures called Crakers, produced by Crake in his top-secret Paradice project.

Oryx and Crake is the first of the trilogy, Year of the Flood the second, and Maddaddam concludes it. Oryx and Crake sets the scene. The time is in the future, however, the elements making up this future have their recognizable roots in our present. The world is divided into the haves and have-nots. The haves are the corporations, and their employees live in corporation compounds. They are given better lifestyles than the working-class pleebland inhabitants. The raison d’être of the companies is to produce, in competition with others, products promising eternal youth, vitality, sexual prowess and the promise of resulting happiness: AnooYoo, HelthWyzer, OrganInc and RejoovenEsense. OrganInc created pigoons to grow organs for transplant. AnooYou "preys on the phobias and voids the bank accounts of the anxious and the gullible." HelthWyzer manufactures pills for profit, not for health, indeed health is one of their last considerations. In the race for profits, they introduce viruses into their ‘health’ products, to which they can then develop and sell antidotes. Wars over markets are commonplace.

The compounds are policed by private Corporation Security, CorpSeCorps, who control their populations’ movements, by violence and murder, if they deem it necessary. Opposition is not tolerated. A hierarchy exists between the corporations, some being rather less successful and thereby poorer than others. The wealthiest ones still provide real food to their workers; the less successful ones seem to be sliding into the artificial food and conditions that are imposed on the outside world. This setting is the profit-making class, with its more or less bribed employees.

The outside world is called Pleebland (plebeian land, desolate neighbourhoods, where the poor live). The pleeblands still contain cities like "New New York" and San Francisco and hold some attraction for the corporation employees as, while dangerous and diseased, places of entertainment and ‘time out’. Permission and passes are required to go there. This is where the poor live, those at whom the sale of products is aimed.

The story is told from the point of view of Snowman from the novel’s current time, with flashbacks to his past when he was still Jimmy. His best friend at the time, Glenn, is referred to as Crake, a name he picked as a character in an online game the two played called Extinctathon, controlled by the enigmatic Maddaddam.

Both characters have parents who have disappeared. Crake’s father died in a car accident when Crake was very young. Crake believes his father was eliminated for objecting to the practice of introducing disease into the population in order to profit from then selling the remedy. Jimmy’s mother, whom the reader gets to know better, runs away from the compound and protests against their practices. Such defection is dangerous and she knows she needs to disappear without a trace. The corporation tries to locate her, follow her surreptitious messages to Jimmy and interrogate him occasionally regarding her whereabouts. It is likely, although not certain, that Jimmy and Crake witness her execution online.

These two people are not the only examples of resistance to corporate rule. During the coffee war, there is mention of "Union dockworkers in Australia, where they still had unions, refused to unload Happicuppa cargoes". While Crake’s father’s protest is an individual one, these dockworkers act in unison, and they are supported: "in the United States, A Boston Coffee Party sprang up." Jimmy’s mother, too, has clearly joined opposition groups. When Jimmy hears from her or sees her online, she is always part of broader movements.

Crake’s highly valued academic science and maths skills ensure his speedy progression in corporation hierarchy. Jimmy’s verbal skills land him in advertising. Eventually, Crake brings him to the most powerful RejoovenEsense corporation, in which he is a very senior operator. Jimmy’s job here is to run the ad campaign for BlyssPluss, a product to increase sexual performance, protect against STDs, extend youth and function as male and female birth control to reduce global population. Secretly, Crake works on the creation of humanoids, the Children of Crake. These are ‘grown’ in an artificial dome.

Jimmy and Crake both love Oryx, whom they first see in a child pornography film. She is Asian by birth and was sold, as was common practice in her village, to a white man. Her odyssey brings her to North America and Crake later hires her to be a teacher for his Crackers: to explain simple concepts and communicate with them. She also markets BlyssPluss around the world.

When the catastrophe strikes, both Crake and Oryx die violently, and Jimmy takes the Children of Crake to a safe place by the sea. Just how safe this place is, is debatable, as the environment is badly damaged and they need to seek food and other essentials for survival. The children of Crake have been programmed to live on plants only.

This first volume of the trilogy ends as first the Children of Crake, later Snowman, encounter other human survivors. Perhaps playing on a set of fossilized early human footprints discovered on the shore of Langebaan Lagood, South Africa, in 1995, Snowman traces the whereabouts of the humans by following their imprints on the beach. He finds "Two men, one brown, one white, a tea-coloured woman". He is uncertain as to what to expect, knowing his own species, and considers different scenarios of how to relate to them. In the end, he leaves them without making himself known and returns to the Children of Crake, who he knows are naïve, friendly, peaceful, and care for him.

While Oryx and Crake (2003) is set in the Compounds, the second volume in the trilogy, The Year of the Flood (2009), is set contemporaneously in the violent and disease-ridden pleeblands. This is where the novel’s central female characters live, Toby and Ren, relating the stories of their lives and individual survival of Crake’s pandemic. The narrative shift from compound to pleebland is echoed in that from individual narrator to two narrators, from male to female, from isolation to group.

The two women had been members of a religious sect (albeit themselves not terribly religious), the pacifist and ecological God’s Gardeners, who had predicted the apocalyptic Waterless Flood brought about by environmental destruction. As they see it, Crake’s pandemic is this flood. God’s Gardeners is a dropout group, which is not idealized by Atwood, but shown with its own weaknesses. A disagreement over tactics, causes Zeb to leave the pacifist Gardeners and engage in active bioterrorist opposition to the Corporations’ security police. As the narrative draws towards the present, surviving Gardeners are forced into hiding and are hounded by dehumanised criminals (“painballers”), who murder and kidnap.

Echoing the ending of Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood concludes as the main characters find other survivors, including Jimmy, and the two painballers, along with their kidnap victim. They do not kill their criminal captives, but tie them up and feed them. The closing paragraph announces the arrival of Crake’s Children approaching them: “many people singing. Now we can see the flickering of their torches, winding towards us through the darkness of the trees.”

The final book in the trilogy, Maddaddam (2013), is written from the perspective of Zeb and Toby, who were both introduced in The Year of the Flood. Their stories are told in the wake of the same biological disaster. They eventually meet up with Jimmy (Oryx and Crake) and other survivors. Together with the Crakers, they start remaking civilisation, but are still troubled by criminals. Some humans mate with the Crakers, but eventually die out. The end part of the story is told by the human-like the new race. They are peace-loving and environmentally aware.

Atwood’s outlook is cautiously, if thinly, optimistic for the survival of life on the planet. Despite an impending, profit-driven environmental catastrophe, wars, and cynical disregard for human beings, it is the ordinary human beings who have the greatest potential for survival. Very few do survive, but they realise that continued existence can only be achieved in solidarity with one another, not in competition, rivalry, exclusion, and individualism. While the danger is by no means defeated, a return to the awareness our tribal ancestors had of community, the state that Marx and Engels called primitive communism, is essential. And perhaps humankind will only live on in a new, more co-operative version of itself.