Culture and barbarism: the work of Walter Benjamin

Culture Matters is pleased to present this short film by Professor Esther Leslie, Carl Joyce and Mike Quille. Professor Leslie's text is below.

Walter Benjamin was interested in the ways in which art, culture and politics flow together. He made a connection in a line he used a couple of times:

‘There is no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.’

This signals an insistence that all of our forms of culture are simultaneously politically, or socially, enmeshed, in the broadest sense. All cultural documents – artworks, films, novels, poems, statues – are produced within the prevailing barbaric circumstances of class-divided society. That something beautiful or awe-inspiring might be made by an artist relies on a social division of labour that denies most people any permission to be creative. The existence and persistence of culture confirms the validity of the production process that brought it into in being. Cultural documents of all kinds thus work to embellish the rule of those in power, justifying their elevation above the immiserated and disempowered.

The Colosseum is an example of real barbarism taking place in cultural form – for example, in gladiatorial battles, staged to underline the power of privileged families, or in the real executions of condemned people as the climax of stagings of myths. But there are more subtle ways in which culture hinges on barbarism. Cathedrals, full of artworks, carvings, opulence, do not glorify those who built them, but rather give consolation for ongoing suffering and the promise of something better to come.

There is no such solace apparent in the oil paintings of the wealthy, those who are ‘long to reign over us’, – the canvas simply covers over a world of immiseration experienced by those who are not expected to leave any traces of themselves to posterity.

The cities are littered with relics of individuals who are immortalised in granite or bronze and who gained from a barbaric system. Sometimes the wrong is righted, the barbarism inherent in the artefact exposed, the statue brought down, as when the late Victorian statue of Bristol-born merchant and transatlantic slave trader Edward Colston was toppled in 2020.

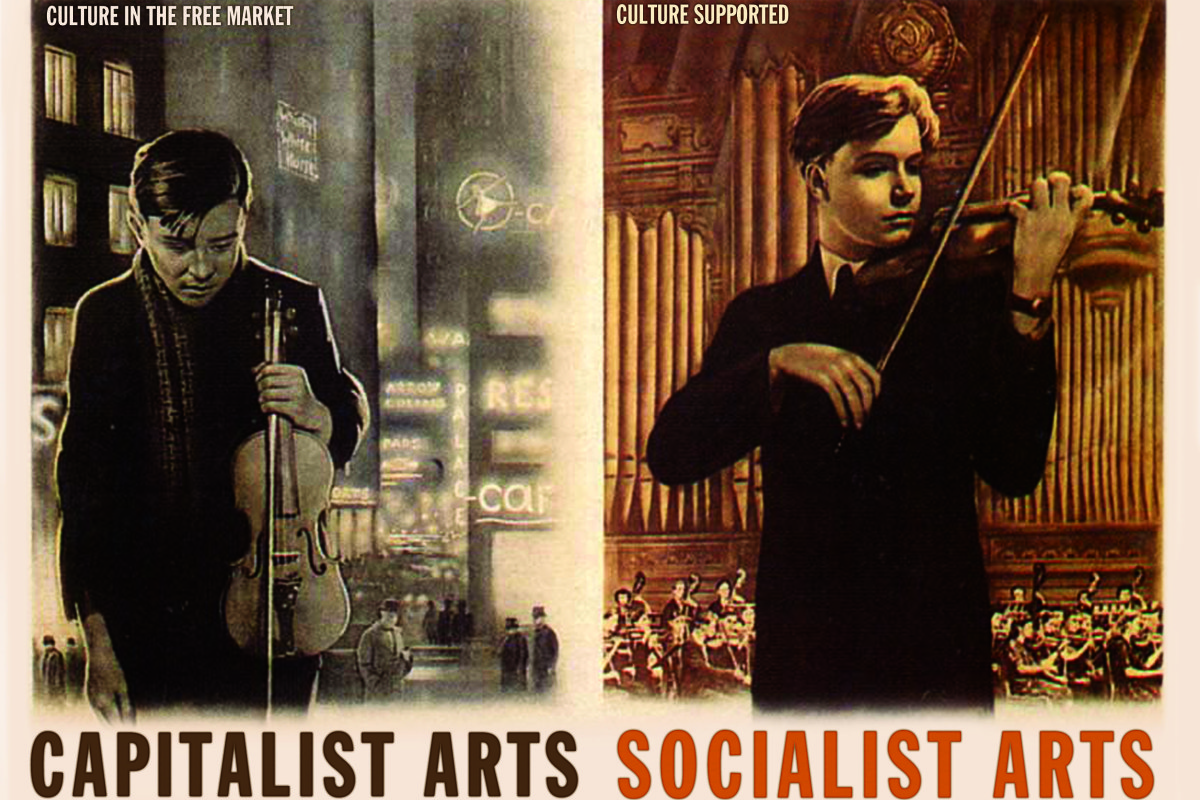

Art and Politics

Walter Benjamin lived through varying types of barbarism – coming of age in the years around the First World War, when experimental and avant garde art movements thrived, often alongside left wing and communist movements. He also lived through the years when the Nazis took power in Germany, fascism dominated various parts of Europe and a Second World War broke out. One of his interests was in how art and politics worked together across time. There is a line in his programmatic essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility’ from the mid-1930s:

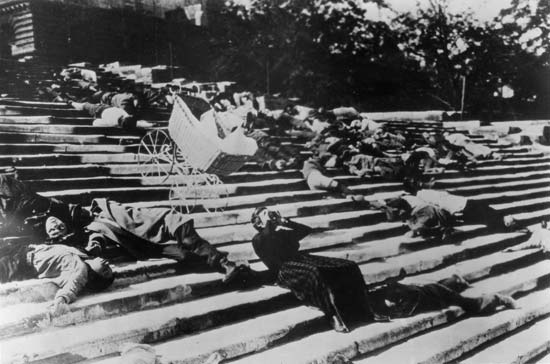

'Mankind, which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympian gods, now is one for itself. Its self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order. This is the situation of politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.'

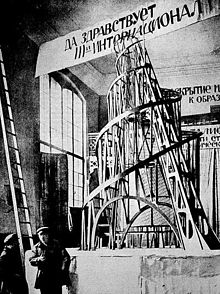

Here Benjamin observes that populations are encouraged to rush headlong into war and mass destruction. Fascism speaks of the glory of war – and some Futurists wrote poems to that effect. War is presented as a dramatic sensation, an intensified experience, like an artwork or a spectacle. Political rallies and parades, uniformed ranks of people arranged in ornamental fashion, blonde housewives with children, were enacted and broadcast using the latest medium of film and radio. They became cultural events. To counter this, Benjamin insists on regarding art as political, as intrinsically political and as a place where a progressive politics of liberation might be carried out. Art and culture might be used not to service the glorification of war or the deification of leaders, but rather as weapons wielded in social and political struggle.

But what kind of art.....?

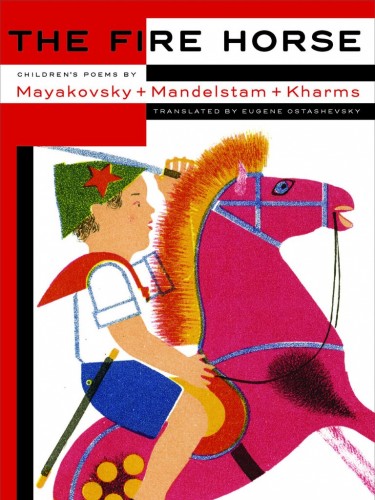

What art then? Benjamin argues that aesthetic choices, such as the choice to paint a picture or take a photograph, to make a collage or a poster, to write a poem in obscure and high-flown language or in the vernacular discourse of the street, the decision to work as an individual artist or as a collective of makers and producers, and so on: These are all political aspects of art.

Is an artist someone who sells work as a commodity – and what sort of a commodity is art? Benjamin’s interlocutors, Adorno and Horkheimer, wrote about something they called the culture industry. This described all cultural production first and foremost for money. Financial models, questions of access, the high price of art, the return on the value of investments, all this is part of the politics of art – and for Benjamin, the work of Brecht, John Heartfield or Eisenstein would be three methods of engaging with this field, in his time, under the conditions of his time, questioning in their various ways value, circulation, ideology, the purpose of art, distraction, propaganda, the relationship of image and world, beauty, horror, lies, violence, war, social relations.

And, furthermore, who is an artist? This too is a question with political aspects – who is allowed to be an artist when the roles the artist should perform have become highly politicised, as in the Great German Art Exhibition of 1937.

The 'brutal grasp' and 'destructive character' of art

'To the process of rescue belongs the firm, seemingly brutal grasp'

Benjamin wrote this line in the Arcades Project in 1931. Walter Benjamin’s aphorism advocates a sudden movement, getting the hands dirty in grasping or grabbing in order to rescue something – what? A better life? Humanity itself? Nature? Art? Benjamin is interested in salvage, in extracting from the jaws of doom, a better life, through a decisive and hard gesture – or at least a ‘seemingly brutal’ one. Sometimes, he argues, it is necessary to take decisive action – and not even to reflect on that too explicitly.

This idea of acting sharply and brusquely comes together with a figure that Benjamin invented: the ‘destructive character’. The ‘destructive character’ is a type without memory, opposed to repression in its political and psychic senses, who – causing havoc by cutting ways through, by liquidating situations – removes the traces which sentimentally bind us to the status quo. They do this in order to make possible modes of behaving or misbehaving, which are appropriate to the brutal conditions of the world and to their dramatic overthrow. The destructive character rejects past traces, has abolished ‘aura’ and with it sentimentality about things, including his own self.

The destructive character is the enemy of the comfort-seeking ‘etui-person’, who cossets everything in velveteen cases and plush, trying to individually make the hard edges of the world temporarily comfortable and for him or herself alone. In ‘The Destructive Character’, Benjamin writes about those who try to preserve the world – and art – as it is:

'Some people hand things down to posterity by making them untouchable and thus conserving them; others pass on situations, by making them practicable and thus liquidating them. The latter are called destructive.;

Benjamin is sometimes portrayed as a melancholic and fated individual who was unable to make his way in the world and prone to abstract theorizing. In actuality his writing about art was carried out in close conjunction with practice – including his own: for example he made many radio shows in the late 1920s and early 1930s – and he wrote fables and stories and poems.

He also worked with others who were questioning the ways in which art might contribute to social and political struggle, in the most revolutionary way, with implications for culture and social forms. For one, he was close to Bertolt Brecht, Marxist poet and playwright. Brecht praised a certain kind of vulgar thinking – forwarding the idea that truth is simple, graspable.

The new barbarism: shock and awe, work and war

Sometime between the spring and the autumn of 1933 Benjamin wrote a short reflection titled ‘Experience and Poverty’, which considered the new reality of world war in the twentieth century. Twentieth century warfare had unleashed a ‘new barbarism’ in which, observes Benjamin, a generation that went to school in horse-drawn trams stood exposed in a transformed landscape, caught in the crossfire of explosions and destructive torrents.

Benjamin’s was no lament for the old days, for those were unliveable for the property-less and the habits engendered by the cluttered and smothered interiors were unhealthy and uninspiring for the propertied. ‘Erase the traces!’ Benjamin proclaimed – a line he took from a poem by Brecht. Benjamin enthused about a ‘new, positive concept of barbarism’ and he championed the honest recorders of this newly devalued, technologised, impoverished experience: Paul Klee, Adolf Loos, and the utopians Paul Scheerbart and Mickey Mouse. In all of these the brutality and dynamism of contemporary existence, including its technologies, was used, abused, mocked and harnessed.

Property relations in Mickey Mouse cartoons: here we see it is possible for the first time to have one’s own arm, even one’s own body, stolen. Benjamin wrote about Mickey Mouse first in 1930. What fascinates him is the fact that Mickey Mouse can alienate from himself an arm or a leg, he can give up his body in order to serve the power structure operative within the cartoon. That fascinates Benjamin as an image of what we are required to do in order to survive or to live our bare lives. Experience, a sense of consistent development over time, wisdom and continuity, no longer is relevant in the modern world of shock and awe, factory work and war. These films disavow experience more radically than ever before. In such a world, it is not worthwhile to have experiences.

Benjamin has a very sober sense of what capitalism requires of the body, the whole thing about film and its shock aesthetic subjecting the human sensorium to a type of training – this is painful. Benjamin thinks that there is a potential there to understand how we inhabit the world with technologies that might, indeed, alienate parts of our body in order to become this partly human, partly technological, endlessly refungible and brutalised subject. Audiences flock to these films not primarily because they are artworks of the mechanical age of reproduction – that is just a condition of their existence. They flock to them because they recognise something in them that gels with their own existence:

So the explanation for the huge popularity of these films is not mechanization, their form; nor is it a misunderstanding. It is simply the fact that the public recognizes its own life in them.

History and change

The final piece of writing by Walter Benjamin, from 1940, was not published. It is a few sheets of paper thinking about history and change. Benjamin advocates a mode of thinking that could overpower the political situation. It is written at times in an elusive language and it is not a manual. It is an effort at the production of an attitude, one that is open to imagining the breaking open the continuum of history or arresting it, one that sets out from the positive aspects of shock, breaking through the picture of history – a warlike, explosive assault on the state of things, snatching an evanescent memory that flashes up at a moment of danger.

Benjamin’s strategy addressed the idea of the image or picture of history. These metaphors cannot be simply translated into practical action. Or rather they might import themselves only at specific, charmed revolutionary moments. As he put it in one of the theses in Selected Writings:

'The consciousness of exploding the continuum of history is peculiar to the revolutionary classes in the moment of their action. … in the July Revolution an incident took place which did justice to this consciousness. During the evening of the first skirmishes, it turned out that the clock-towers were shot at independently and simultaneously in several places in Paris.'

History is exploded as an act of ‘genuine’ progress, which does not move simply forwards. Revolutionary time is not clock time, but rather the time of the present, filled with the moment of acting, an acting which is then re-invoked as a conscious reflection on what brutal, disruptive act brought the new time into being. A new calendar, such as that inaugurated in the French Revolution, should mark the discontinuity that has been brought it into being in its naming, its re-divisions, its spaces of commemoration – unlike the Weimar republic, born of a compromised revolution in 1918 and 1919, and which is unable to acknowledge its own constitution as a break in time, a break in tradition – and so returns to old times, business-as-usual.

What Benjamin asserts in the essay ‘Experience and Poverty’ is the necessity to adopt brutal modes of thought and action not as a freely chosen strategy as such, but as a mimetic adaptation to the brutality that is the world and as a glimpse into what is needed to carry through a break, a revolution, a change in the state of things. Through a kind of doubling, the negation is negated.

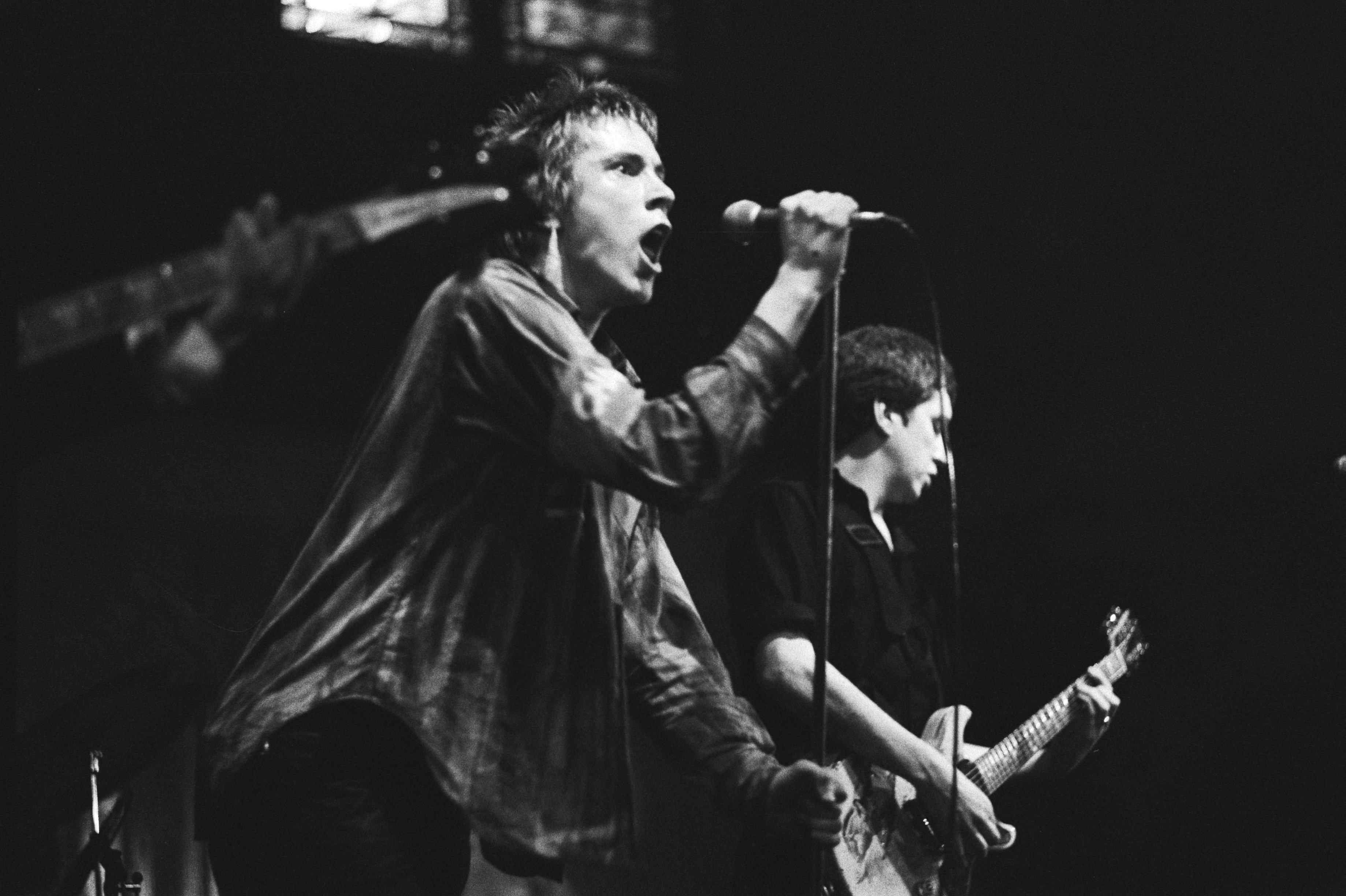

We can find this radical brutality in various and varied documents of culture: in artworks like Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’; in Eisenstein’s montage and editing techniques; in Brecht’s plays and poems; in the Situationist ‘detournement’ of comics; in the music of John Cage or in punk.

There is also brutality in thought: a breaking with thinking as it has been thought to date, an assault on common sense, in order to annul the thinking that justifies, by not drawing attention to, everyday brutality. Brutality in action: a brutal, critical one, in which time itself might be interrupted. The world itself might stop spinning – such is revolutionary political action. The world is brutal and critique might become action on and in the world and its symbols:

‘There is no document of culture which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.’

Sometimes the statues that glorify brutal systems and their agents are kicked over, revealing a connection between culture and the barbaric that exists usually obscured. Such radical acts direct art and politics – and life – towards other possibilities.

You can also hear Professor Leslie talk about Benjamin on Radio 4's In Our Time, here.