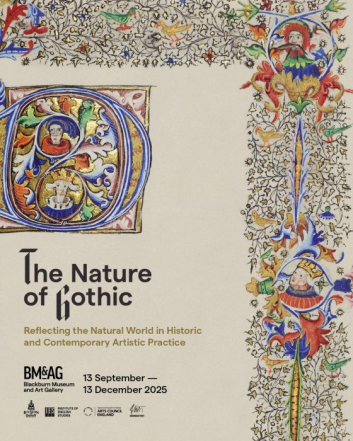

At Blackburn Museum and Art Gallery until 13th December

By Peter Shukie

Blackburn Museum’s The Nature of Gothic offers up treasures of heritage: William Morris’s wallpapers, Rossetti’s goddess, medieval manuscripts from the Hart Collection, and a white deerskin book that once belonged to Henry VIII.

It is a celebration of Gothic revival and artistic splendour. Yet, from a working-class perspective, it also shows how beauty can be used to cover cracks, how some forms of knowledge are preserved for centuries while others are destroyed or forgotten, and how power chooses what lives and what dies in our cultural memory.

One object gleams brightest in the exhibition. It is not the oldest, nor the most precious or the most beautiful. It is a book bound in white deerskin, once owned by Henry VIII. It sits immaculate under glass, the centrepiece of royal knowledge, an emblem of endurance. But its survival tells a darker story. For Henry’s dissolution of the monasteries destroyed countless libraries. Books burned, manuscripts lost, traditions erased — all so that royal power could hold the pen of history. The paradox is stark: some texts survive because others are destroyed. Heritage is not neutral; it is curated by fire.

And this echoes more widely. For every illuminated manuscript that has survived, how many local chronicles were reduced to ash? For every king’s book, how many parish songs, folk tales, or herbal recipes were obliterated? Knowledge that was lived, participatory, handed down around fires or workshops or allotments — swept aside to make space for royal books on display.

In the north west, Lancashire, in Blackburn itself, this tension is especially vivid. The museum itself was founded in the nineteenth century, built on traditions of Victorian collecting that prized the exotic, the rare, the monumental. Yet it stands in a town forged by mills, by strikes, by waves of migration and revolt. Around these streets, knowledge was not ornamental but insurgent: union pamphlets, chapel songs, stories in dialect, whole traditions that spoke to survival and resistance. To walk from the gallery of deerskin books into the town outside is to feel the split between what heritage preserves and what it erases.

We inherit not just what was preserved but also the violence of what was lost. The deerskin book is both treasure and gravestone.

Astarte Syriaca by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Rossetti’s Astarte Syriaca hangs nearby, monumental and mute. She appears a goddess, yet her face is Jane Morris, daughter of an Oxford stableman, later wife to William Morris. Her working-class origins vanish beneath the paint. She is made eternal, but silent. Like emperors who seized Egyptian obelisks to proclaim their dominion, Rossetti seizes a woman’s likeness and transforms it into symbol. The goddess endures. The living woman’s voice does not.

The erasure of working-class women

What does it mean when working-class women become immortalised only as muses? Jane Morris, like so many others, is celebrated for her face, not her voice. Her labour, her wit, her anger, her sense of life — all erased, while her body becomes the eternal property of art. This is a pattern that echoes through time: workers appear as raw material, as backdrop, as inspiration, but rarely as authors. Their contribution is absorbed into the symbolic economy of culture, while their living selves remain unheard.

And so we circle the room to manuscripts filled with vines and grotesques in their borders, admired for their marginalia. But the margins are not freedom; they are containment. The centre of the page — scripture, law, command — is protected. Invention is relegated to the edges. This maps too neatly onto class. Working-class lives appear in cultural margins, used as colour or comedy, but the centre is always reserved for authority. We are visible as decoration, but absent as authors.

The exhibition takes its title from John Ruskin, who praised the crooked mark of Gothic stonework as a sign of human freedom. His words have rung down the decades as if they promised salvation. But Ruskin’s sermon was for elites. He admired the irregular mark, not the hunger of the mason who made it. He aestheticised poverty but offered no sustenance. Gothic became symbol, not solidarity.

Empathy without redistribution

That echo continues today. At the recent Ruskin College panel during the Labour Party conference in Liverpool — a discussion explicitly about education, class and inequality — the same pattern replayed. Ruskin’s name carried more weight in the room than any working-class speaker. The panel was dominated by Oxbridge graduates, many rehearsing their “rise” from working-class beginnings. The focus was on personal ascent, not collective change. It was empathy without redistribution, heritage without challenge. And once again, the working class were objects of reflection, rarely subjects of the conversation. Ruskin remains central in spaces of power; the living, breathing responses of working-class people remain peripheral.

Strawberry Thief by William Morris (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

And then comes Morris’s Strawberry Thief. It is celebrated as “truth to nature,” but this is not nature — it is gardening, horticulture at its most benign. The cheeky intrusion of avian life into the cultivated landscape of middle England, a small rebellion safely absorbed into pattern. The design shows a bird stealing fruit, but only in the confines of repeat and symmetry. It is the idea of nature after it has been pruned and shaped, nature made ornamental.

This contrast is sharpest when set against the lived environments of the North West. For working people, the landscape was slagheaps, factory smoke, allotments clinging to the edges of mills. To see “nature” preserved in Morris’s wallpaper is to see a pastoral fantasy tailored for those who could afford to live with it. For others, nature was survival, cultivation by necessity, hands in soil to grow rhubarb in backyards, not birds stealing strawberries in a designer’s repeat. Yet the wallpaper, like so much of the Gothic revival, masked these divides. It offered moral beauty as spectacle, while the conditions of inequality were left untouched behind the papered wall.

Art as participation, not representation

All these acts — the book in its case, the woman made goddess, the margins of manuscripts, the wallpapered wall — are acts of representation. What they lack is participation. Knowledge is not only what survives in vitrines or behind velvet ropes. It is also what communities do, make, share and live. In January, the same gallery will host Blackburn’s Art Open, filling its walls with work by local people: paintings, photographs, sculptures, collages. These works are not meant to be heritage objects. They are meant to live, to spark conversation, to exist as part of a community. Here, art is not a sermon. It is a practice. Not preservation, but participation.

This is the contradiction revealed by The Nature of Gothic. Books survive because others were burned. Goddesses are created by silencing the living. Margins reveal boundaries rather than freedom. Wallpaper decorates inequality. Ruskin still preaches, but offers little bread. Yet the cracks remain visible, if you choose to see them.

That is the knowledge that survives. And it survives not because power allows it, but because people insist on making it live. Exhibitions like The Nature of Gothic are valuable, not only for the treasures they preserve but for the questions they provoke. They remind us that knowledge has always been contested, that what is displayed is often what survived the fire — and that survival can be as much about erasure as about endurance.

It is tempting to treat this as history, to imagine that the marginalisation of voices belonged to the past. But it can, does and is happening now, whenever power speaks for people instead of listening to them, whenever working-class lives are represented but not present. To recognise this is to accept responsibility: each of us has a role in ensuring voices are not sidelined, that the cracks are not papered over, that culture is not reduced to wallpaper.

Especially now, in times of division and turmoil, we cannot afford silence. A working-class Gothic insists on presence. It demands that all voices be heard — not as echoes, not as margins, but as the living centre of culture.