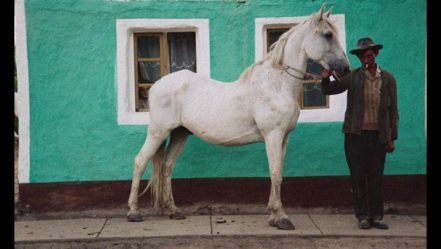

Photo credit: Marco Anelli

By Jack Clarke

Factory International looks like it was dropped from the sky by some intergalactic logistics company. A monument to the future built in the footprint of the past. From the outside, it’s all glass, angles, and ambition a symbol of the ‘new North’, shiny enough to make the council brochures proud. But beneath the steel and branding lies the same old questions around cultural democracy: who gets to decide what culture looks like, and who it’s for?

This is the building I somehow find myself in semi-regularly as part of Young Curators 24, a programme that exists to let an eclectic bunch of young artists, thinkers, and organisers have a say in what art gets pumped through Manchester’s newest cultural megastructure, a small but vital experiment in shared power. It’s a bit like being invited into the Ministry of Culture after the revolution and told to make yourself useful.

Somehow, me, a working-class bog creature from Salford, ended up inside, in a place where usually even the chairs are nailed down for fear I might nick them. Because that’s the quiet truth behind the arts: access is political. Culture might be for everyone in theory, but in practice, it’s often locked behind the same doors it claims to open. So when they do let us in, the ones who didn’t grow up fluent in gallery-speak or grant applications, it matters. It changes the air a bit.

On Sunday the 12th of October, they locked the whole place down like a fascist gulag. Scanners, snipers, security, metal detectors, and a ticket number that felt more like an inmate tag than an entry pass. All of us are waiting for Marina Abramović’s Balkan Erotic Epic, the artist’s latest four-hour fever dream about sex, power, grief and God. You could feel the energy in the queue: the art world veterans pretending they weren’t star-struck, balding men waiting to tell you about how great the Hacienda was, the students dressed like they were hoping to be discovered by Dazed, the odd Salford head just here for shits and giggles.

A brass band started up in the foyer, proper Balkan brass, not the fake wedding version you hear on Spotify, and Marina herself appeared. Small, fierce, glowing like she’d swallowed a torch. She gave a short speech about the work being born from her heart and guts and then said something that stuck with me: “This show could only happen in Manchester.” And you know what? Maybe she’s right.

We were herded, and I mean herded, through the corridors into the warehouse. The moment you step in, you’re hit with sensory overload: screens, mist, naked bodies, chants, crying, the smell of brass polish and sweat. There’s no traditional seating, no safe distance. You move through it or it moves through you.

The first thing you see is Tito’s funeral. You’re not eased into it, you’re dropped straight into history mid-wail. A propped-up figure of Josip Broz Tito, the communist leader who led Yugoslavia’s partisan resistance against the Nazis before ruling for thirty-five years, lies at one side, draped in the weight of his own mythology. Centre stage stands a singer, Svetlana Spajić, monumentally swathed in black taffeta, a towering felt headdress slicing through the dim light as she unleashes a four-hour lament that feels like it could raise the dead.

Photo credit: Marco Anelli

Around her, hired mourners beat their chests in rhythm, the narikače, professional grievers pulled from Balkan tradition, women who once got paid to cry the pain out loud. Death here doesn’t go quietly; it’s choreographed, it’s communal, it’s operatic. Cutting through the spectacle, a woman in a grey suit, Danica Abramović, Marina’s mother and former head of the Museum of Art and the Revolution, steps forward, lays a bouquet, and salutes the corpse of Tito with the mechanical grace of old authority. She vanishes back into the dark, like ideology itself retreating from the stage.

It’s a state funeral turned theatre, a lament turned loop, a whole nation mourning its contradictions while the rest of us stand there, unsure whether to clap, cry, or salute.

From there, without meaning to, I somehow stumbled straight into what can only be described as a full-scale pagan mating ritual between man and mud. One minute you’re wiping your eyes at Tito’s funeral, the next you’re watching a dozen blokes tenderly, and I mean tenderly, making love to the soil like they’ve just remembered where they came from, while opposite this women flash their vulvas at the sky to scare the gods into stopping the rain. It’s absurd and holy and weirdly moving. I thought about the farmers of Lancashire, muttering to the weather under their breath, and wondered if it’s really that different. In the Balkan mythos, the erotic isn’t pornographic, it’s survival. You fuck the ground so the crops grow. It’s labour, not leisure.

Photo credit: Marco Anelli

One that really stood out to me and was possibly my favourite part of this four-hour show was the Kafana complex, a full-blown Balkan pub built inside the venue, red lights, smoke, tables, songs, ghosts. This is where Marina’s mother loosens her collar and starts to dance, finally giving in to the desire she spent a lifetime repressing. The atmosphere shifts from mourning to mania. Men cry, women laugh, an opera singer belts out a lament that sounds like both orgasm and death. It’s the most fun human thing I’ve seen in a long time.

Photo credit: Marco Anelli

Watching it all unfold, I couldn’t help thinking about Yugoslavia’s Black Wave cinema of the ’60s and ’70s, filmmakers like Želimir Žilnik, Dušan Makavejev, and Karpo Godina. They made work that mocked authority and exposed the contradictions of socialism with dark humour and surrealism. These films were banned for being ‘anti-Yugoslav,’ but really, they were too honest. They weren’t afraid of dirt or absurdity; they celebrated life’s mess as a form of resistance. Balkan Erotic Epic feels like a continuation of that lineage. Abramović channels the same energy, the political through the physical, the personal through performance. Where the Black Wave used celluloid, she uses flesh. Both tore through ideology to find the human underneath.

Litany of Happy People. Courtesy of Karpo Godina.

That tension between devotion and destruction has always been her compass. Born under Tito’s rule, raised by two war-hero parents, a mother who enforced bedtime well into adulthood and a father who was rarely home, Marina learned early that love and discipline were the same thing, that control was both shield and shackle. So she made her own form of rebellion. Her early performances, cutting herself, burning herself, breathing until blackout, weren’t about shock, but survival. About discovering what’s left when you strip away everything but the will to endure.

Balkan Erotic Epic hits hard, because it’s autobiography reimagined as folklore. The partisan daughter becomes the witch-mother. Ideology becomes a myth. Eroticism becomes a kind of faith. Beneath the nudity and ritual, you feel the grief of a generation for lost countries, lost ideals, and the collective joy that once bound people together before everything fractured into private screens and personal brands.

Young Marina, Belgrade, 1951. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives.

Standing there in Manchester, I kept thinking about how that story doesn’t just belong to Yugoslavia. It belongs to us too. This city was built on collective labour, mills, unions, movements, and though its bones still hum with that energy, so much of it’s been flattened, polished, and sold back to us as ‘heritage.’ The old rituals of solidarity have been replaced by the new rituals of capitalism. We scroll instead of sing. We curate instead of connect. We build creative “districts” where communities used to live. Abramović’s work, in all its ecstatic chaos, feels like a warning, that if we forget what it means to feel together, we lose more than culture; we lose our humanity.

She said this show could only happen in Manchester, and maybe she’s right, but only the Manchester that still exists beneath the marketing gloss. The one that built its own culture out of derelict mills, payday loans, and sheer stubbornness. Because this city still knows what it means to turn grief into dance, to turn struggle into song. It’s got its own kafana energy, pint-glass hymns and warehouse communion, where everyone’s a bit broken but still finds a way to sing.

By the end of the four hours, I was wrecked and sweating cobs. tanding in that strange mixture of exhaustion and awe, I found myself wondering what my grandad would’ve made of all this, a man who worked every job under the sun, from scrapyards to factory floors, just to keep food on the table. He’d probably have called it daft at first, then gone quiet, like he always did when something hit a nerve he couldn’t name. Because beneath all the performance and philosophy, there’s something deeply human here, a reminder that desire, labour, and grief all come from the same place. That even when the world falls apart, we’re still reaching for touch, for connection, for meaning in the dirt.

Walking out, phones still locked away, there was this weird collective quiet, like everyone had just been through the same exorcism but didn’t know what to call it. Maybe that’s the point.

Marina Abramović doesn’t offer answers; she offers endurance. She makes you sit in the discomfort until it stops feeling like discomfort and starts feeling like truth.

Photo credit: Marco Anelli

If I had to sum it up, I’d say this:

Balkan Erotic Epic is what happens when grief finds its rhythm. When history refuses to die quietly. When the body becomes the last honest language left.

And in that sense, yeah, maybe it really could only happen here.