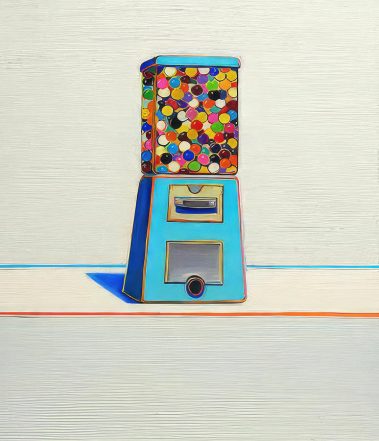

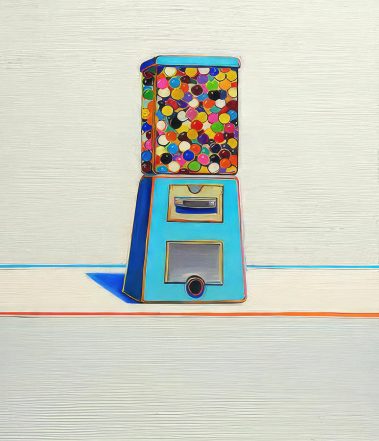

Gumball Machine, by Wayne Thiebaud

By Nick Moss

How do you paint the fire while being consumed by the flames? What possibilities exist for artistic practice to resist commodification and model alternative forms of resistance, at a time when the market appears to be the only real means by which artists can survive and support themselves?

In the USA, artistic censorship via withdrawal of government funding is becoming routinised under Trump. In the UK , with the proscription of Palestine Action, and the proposed removal of the right to jury trial, free political speech is being proscribed, and the remaining democratic input of our class into the decisions that fundamentally affect our lives (whether or not we are guilty of a crime, according to a jury of our peers rather than a rich, white, male judicial elite) is being taken away.

Does the idea of the autonomy of art have any real, consequential meaning, when art survives on a mix of institutional support, state funding via ACE and as an investment vehicle for private capital/ rent extraction by commercial gallerists? In particular, how can figurative art assist a critical culture in responding to capitalism’s representations of itself, when those representations overwhelm us to such an extent that they surround us like air?

Three artists with current London exhibitions help us map out ways in which art can retain an oppositional practice without being reduced to the simply propagandistic. (I’ll argue at some other point that we should not discount the propagandistic function of art – capitalism has an ideological apparatus that propagandises for commodity production, exploitation and profit extraction being the ultimate end of history. We shouldn’t flinch therefore from using any medium available to us to argue for the alternative).

Kerry James Marshall: Black and Beautiful

Kerry James Marshall’s The Histories (Royal Academy until 18 January 2026) combines erudite exploitation of the history of figuration and mastery of technique with a resolute determination to place the lived experience of black communities at the forefront of his work. Marshall was born in Birmingham, Alabama in 1955, and began his artistic career at a time when postmodern irony and refusal of content was the norm.

Marshall turned his back on all of that. His work draws on the history of the Civil Rights movement, the iconography of black commercial magazine-based artwork, Kongo nkisi nkondi power figures and Voodoo veves. He also has the technical prowess of, and deep familiarity with, the work of painters such as Courbet, Picasso and Vermeer. This is a large-scale showcase of works from across his career and shows his paintings broadly addressing two themes – an idealised, utopian black community, and an oppressive, violent reality.

The utopian manifests itself in works such as his Garden Project series, which take as their theme the ‘Garden’ public housing projects which replaced slum housing in cities such as Chicago, and were then themselves then starved of funding. The Garden Project series imagines what they could have been-with gardeners in church-best clothes, bluebirds, pink flowers, Easter baskets. (Bluebirds fly across the scenes of many of Marshall’s paintings, even some of the bleakest, as if as a reminder that things could always be otherwise.)

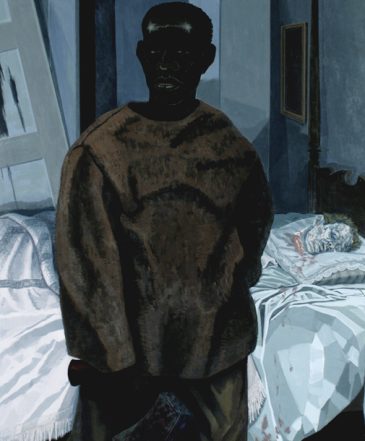

The other side of this though is that Marshall’s engagement with the reality of black history then hits you like a hammer between the eyes. His Black Painting, made using various shades of black pigment, slowly reveals itself to be (possibly) a scene seconds before Black Panther leader Fred Hampton was assassinated in his apartment by Chicago police in 1969.

I say “possibly” because other details don’t fit – Hampton’s bedside reading appears to be Angela Davies’s autobiography, which didn’t come into print until 1974. History – like the pigments overlaid in Black Painting – contains layers which cut across and overlay each other. It has to be worked at – it is elusive, hard to get a fix on, evidence needs to be properly assembled.

Other works here adopt a similar approach. His Middle Passage paintings show history as fragments or wrecks, Africans trading other Africans to slavers; a large picture of a Black cop looking like the stereotypical cop from Electra Glide In Blue, almost homoerotic in his masculinity as he sits on the front of a police cruiser, staring forcefully ahead. And we have to work out if this is a simple image of black pride, or the point where black power becomes a kind of fascism.

Marshall refuses to tell us. We have to map it out for ourselves. We cannot, though, just look, just soak it all up. The combination of choice of image and skillful application of technique means we have to actually react, be alive to the work. The most stunning, shocking, exhilarating work here is the painting of Nat Turner (above), in his master’s bedroom during the 1831 Southampton insurrection, holding an axe in one hand and his master ‘s severed head visible on the bed. Turner stares us down fiercely, and like Marshall’s art is entirely proud and comfortless. As Marshall states: “I am trying to establish a phenomenal presence that is unequivocally black and beautiful. It is my conviction that the most instrumental, insurgent painting for this moment must be of figures, and those figures must be black, unapologetically so.”

Kerry James Marshall has achieved a success that is entirely without compromise, by believing in figurative painting in an age that told us all this was passé; by believing in the political possibility of art when irony and pastiche were at the forefront. His art is affirmative, but also complex, and bracing.

Dana Schutz: vicious yet tender satire

At Thomas Dane Gallery, London, until 20 December 2025, is One Big Animal, a show of new works by Dana Schutz. Schutz takes the opposite approach to Marshall. She paints the world as an already absurd nightmare, populated by self-consuming grotesques. Schutz’s antecedents are Dali, Bosch and Philip Guston, painters who saw life as effectively a degraded burlesque, where one man-monster would whip another to no purpose or pleasure, and Klansmen would drive in cartoon cars round a small town deathscape. She also brings to mind Robert Crumb.

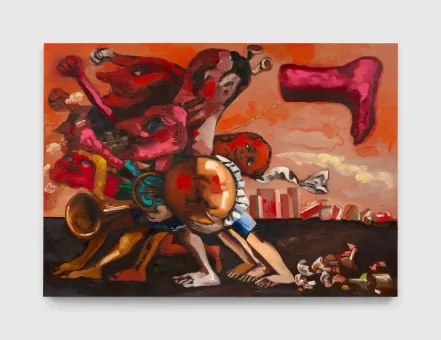

The particular images here though are all entirely the stuff of her own circus. A walking ship carries a Cyclops figure and a collection of giant heads, while stepping on a floor of mud and what may or may not be eggs, like a scene from Georges Bataille ‘s fantasia of the perverse. In The Rally (above), a mass of bodies and limbs collide, like a wheel, or the directionless, pointless tumble of a cat fight.

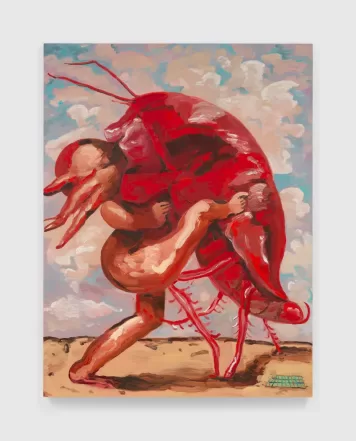

In The Kiss (above), a human figure fights with/embraces a red bug. The point is its ambiguity, I think. Let’s say the red bug is Capital (a version of what Rolling Stone writer Matt Taibbi in 2010 said of Goldman Sachs, but intended to apply to capitalism per se: “a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.“)

In The Kiss, the human figure is both fighting and embracing, and doesn’t know which is which, and will succumb either way. Schutz is an extraordinarily skilled artist – her use of colour to illuminate this tangle of obscenities is superb. More than that, though, she is a vicious, and yet also somehow tender satirist. This is the Hell we live in, the Hell where Pete Hegseth and Donald Trump fill American cities with troops and it eventually becomes the norm that people live as if they are under occupation, but think that the threat comes from outside, not from their own government.

Satire here, as in the plays of Alfred Jarry, means looking full on at reality and peeling away its illusion that it is the best of all possible worlds, spitting in its face, and saying the act of mockery and the end of illusion are the starting point for getting to somewhere else.

Wayne Thiebaud: exposing the trick of consumer capitalism

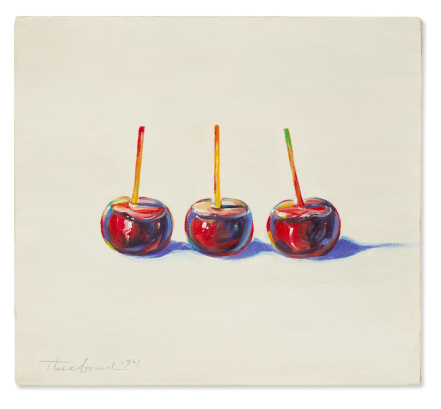

At the Courtauld Gallery until 18 January 2026, is American Still Life – paintings by Wayne Thiebaud of the quintessential modern Americana of cherry pies, gumball dispensers, cake slices, pinball machines, and hot dogs. Thiebaud, (1920-2021) was often grouped with the Pop Art movement because of a thematic overlap with their depictions of consumer capitalism. He, however, saw his work as rooted in the still life tradition of Manet, Cezanne and Bonnard, and saw the works of his contemporary, the Italian still life painter Giorgio Morandi, as a key inspiration.

What makes his work so fascinating though is the way his approach to his themes brings out something unique about the capitalist commodity-form . Andy Warhol’s screenprints of soup cans, dollar signs, flowers, Marilyn Monroe, drew out the nature of mass reproducibility of the commodity, and was an essential and truthful response to the 1950s as a decade of abundance.

Thiebaud does something entirely different. He brackets out everything from the scene except the commodity itself. There are no consumers – no one buys the key lime pie, the salami slice, the gumball. No one plays the pinball machine, or eats the ice cream or the toffee apple (above). The commodity thereby becomes decommodified, restored to a simple item of use-value, abstracted from the intended process of exchange. In doing so, Thiebaud thereby highlights the strangeness of the commodity-form, what he calls the “sweet promise” awaiting the “grimiest kind of copper money.”

In Thiebaud’s work, the process of exchange is forever delayed. If you look closely, the gumball machines have no release handles. But this then begs another question – and is the shadow waiting to fall across the stage – what happens to commodities like toffee apples, ice cream, cheese and salami when they have no consumers? Eventually they spoil, they melt. They have no use value as such. They are produced solely for exchange and separated from that process they endure a kind of beautiful death. This is the darkness that haunts Thiebaud’s still lives.

There is much else here to enjoy. Thiebaud’s brashness in taking yoyos, cake slices or pinball machines (and a Coke bottle instead of the milk jug that is the typical object of still life painting) as suitable subjects for close observation; the way he uses skills learned as a commercial art illustrator to bring consumer objects to life (“…white, gooey, shiny, sticky oil paint spread out on the top of a painted cake becomes frosting. It is playing with reality”); the gentle ribbing he gives Abstract Expressionism by turning the bottom couple of inches of many of his paintings to a pattern of stripes a la Barnett Newman as if to say “I can do that too”; the way he seeks to bring the “relationship between paint and subject matter …as close together as I can possibly get them” so as to expose “the trick of painting.”

All of this adds to the strength of what’s shown. But what really matters is that Thiebaud both celebrates the simple beauty of – and also exposes the trick at the heart of – consumer capitalism. And does so without telling us anything. Just by painting what’s there. And asking us to look, not just glance. Look. And think.