By Nick Moss

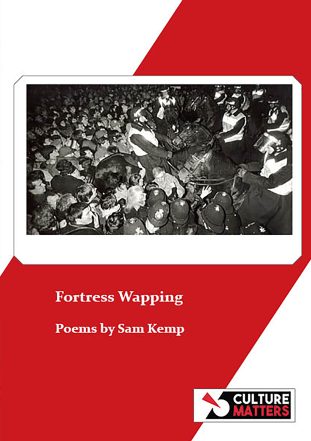

Fortress Wapping is the outcome of a research project by Sam Kemp, and his colleagues Dr Amil Mohanan and Izi Snowdon, into the 1986 News International strike, using material produced by printworkers and their supporters archived at the Marx Memorial Library, along with interviews with printworkers and trade union officials.

Kemp states that” Poetry may seem like an unlikely form in which to explore industrial relations, but any conflict is about narrative and language, the stories we tell ourselves and the stories which are told about us.” What makes the poems particularly alive to the challenge of telling the Wapping story is the use of cut-up (a la William Burroughs) as a poetic method. Some of the poetic material is chopped up, displaced and pasted on the right-facing pages, and the main poems themselves also have a sense of being re-ordered before being set down, so that no text appears settled and the narrative of the events is never simple, it’s always slightly out-of-reach. This works to prevent the poems being simply didactic and renders them numinous in a way which gives them a particular and quite striking beauty, given their subject matter.

The Miners’ Strike of 1984-85 was intended as a symbolic victory by Margaret Thatcher’s government over the best organised and most militant section of the labour movement, and a clear statement that all the machinery of violence available to the state would be deployed against labour to achieve Thatcher’s goals. The Wapping strike was intended by Rupert Murdoch and Thatcher as a first step into Capital’s new age, in that the dispute was about new developments in newspaper printing and production, but just as much about the state’s willingness to mobilise to support industry in dismissing whole workforces with impunity.

Murdoch intended to dismiss 90% of printers and move from hot metal printing to new, cheaper, print technology. The News International group of newspapers would move from Fleet Street to a new site in Wapping – an encampment of barbed wire and CCTV that became known as “Fortress Wapping.”

Over 5000 copytakers, compositors, linotype operators, machine room personnel, publishing room employees, clerical staff and journalists came out on strike on 24 January 1986. All were then sacked by Murdoch’s News International. The strike lasted for 54 weeks and resulted in 1262 arrests. As in the Miners’ Strike, the police in riot gear charged strikers and supporters, with riot shields and batons, and mounted police drove their horses into crowds of strikers.

Kemp’s poetry is intended to disorient, so that the reader has to make sense of a flood of information while still within the poems. Thus, from some of the cutups, “They speak in reptiles”, “Snatch squads catch my wife in an Act of Parliament”, “St Katherine’s Way squirms with the freezing weight of tabloids”, “Most lies are syrup and gravel in the lungs of powdered breath but the big ones pass in silence.”

This is important to Kemp’s political project – the News International strike was a precursor to the media-saturated environment of today – a multitude of channels from a variety of sources, all spewing out falsehoods and denouncing facts as fake news. Without Murdoch’s victory at Wapping there would probably have been no GB News and no pretence by a thousand and one far-right carpet-chewers at being independent journalists with their own YouTube channels.

The language of the poems therefore feels as if it necessarily mirrors the language deployed by the heralds of that new age, as it was portrayed in 1986. Thus “money builds on sound/and how the ghost of its wet timber/ slips sodden through every dockland.”

After the Wapping strike, Docklands became a codename for warehouse property development, and the glass and steel dick-waving of Canary Wharf, all secured ultimately through the “black-booted overflow/of police hours in the rotting docks/ bursting kaleidoscope at desktop/ and the glass clouds of tomorrow.”

Doreen Massey pointed out that what Marx called the annihilation of space by time is in fact a question not only of time-space compression but also of power geometry:

It is…about power in relation to the flows and the movement. Different social groups have distinct relationships to this anyway differentiated mobility; some people are more in charge of it than others; some initiate flows and movement, others don’t some are more on the receiving end of it than others; some are effectively imprisoned by it. (Doreen Massey, Space, Place and Gender, Polity Press 1994 p. 149.)

Conveying how this works is difficult. Showing the relations of power between workers and Capital, when Capital is globalized and digitalized and there is less immediate face-to-face interaction between wage labourer and individual capitalist in a clearly defined local workplace is challenging, because a relationship of exploitation is necessarily not something you can pin on a board like a moth. It is always a step ahead, always a creature of the shadows.

Kemp’s poetry at times here gets close to the essence of this: “Chase lorries to 1986 where new ground births/yokes and union badges and no time to think/and you trip on a brick which once smashed the sky/ while Concorde noses the clouds and looks/ to a slipstream above a silver narrowing of the money”, and particularly in the poems Tradecraft “(the voice of their storied sounding over the plains/ which today shines under your fingernails in a hum of light/ information and tabloid graphics; the throat of a guttural day”) and Trains Shine Through the Home. In charting the ways in which Capital now masquerades as magic (as a volatile, purportedly unpredictable and uncontrollable regression from Weber’s description of capitalism as rooted in rational accounting and calculation) Kemp does something with his poetry that is remarkable here.

The book is beautifully produced and illustrated, with both cut-ups and materials produced by striking printworkers and support groups during the strike. If I have a criticism, it’s that the poems for the most part do not capture the level of violence with which strikers were confronted, or the extent to which they responded with force in return. It’s there in Termination of Contract’s “caved in skull of a news van” and The Legal Observer’s “lorry doors lined with razor blades and diesel song” but the level of violence the state dished out was an attempt to intimidate the strikers and their supporters and it’s important to be clear that this did not go unchallenged. As an example, the Radical History Network article Memories of the Wapping Print Dispute includes the following recollections:

Police violence was not just exercised at the well-guarded picket at Fortress Wapping. They would sometimes raid nearby pubs and select out anyone who looked like a supporting picketer. These could be roughed up and/or then arrested on trumped up assault charges. They were, and probably still are, a feature of their actions. In retaliation, groups of us would wander round the back street hoping to find a police car or two. Once spotted these would be pelted with stones and small bricks until they made a hasty exit.

Saturday January 1987: this was a big demonstration / mass picket. Very large numbers turned up, including football supporters from West Ham, Millwall, Chelsea and Charlton. There was heavy stoning of police lines and severe restriction on their activity.

The politics of violence

Post-Brexit, and post-the prorogation of Parliament in 2019 and its reversal by the Supreme Court, the left has come to fetishize the rule of law. One of the reasons for the success of the far right in gaining an audience within working-class communities has been its explicit lawlessness. Some of the motivation for the 2024 race riots lay in communities joining in as a chance to have a go at the cops.

There is a simple logic to the far right’s politics of violence: it works. If you identify a hotel housing immigrants as a risk to a community or a drain on scarce resources, and then threaten to burn it down, and the next day refugees are bussed out, you have on your own terms succeeded. I think the left is missing a trick. Perhaps we’d be more welcome in communities where we’ve long lost any audience, if as well as waving banners saying, “Stand Up to Racism”, we had already mobilised to “Stand Up to Bailiffs”, “Stand Up Against Disconnections”, “Stand Up to Prevent Evictions.” Perhaps it’s not the method that’s wrong, but the target?

All of this is to say that the violence inflicted by Capital pummels working-class people day-in, day out. In Wapping this took the form of “the ancient charge/of horse and shield down the buzzing cobbles/ of neon-lit investment zones, parting for the press-baron’s tyres/ like the wheeze of law among a skyline of broken toes.”

The breaking of the Miners’ Strike and the News International strike gave us the world we live in now – a world of permanent insecurity, surveillance and self-commodification. It does not mean we have to live in it quietly. “…to be a force or to work a force/ needs numbers needs compulsion/ to slide the steel.” As Sam Kemp puts it, we “breathe steady debit and credit and debit and credit and debit and credit.”

Kemp’s extraordinary poetry shows us how the battle to break Fortress Wapping delivered up, out of our defeat, a capitalist “language throbbing with future”, “the barbed cameras parading/the fortress perimeter: fuck the others.” In the post-Wapping world “the red-necked cranes of the city whistle into cloud cover/ and sell the numb bones of the dead trades to one another.” Kemp shows us though also those moments when “East London ripples with banners which scatter the clouds into union coal dust.” Fortress Wapping reads at times like a history of a moment in the class struggle as written by J G Ballard. Its vital, twisting, language refuses to allow the weight of past defeats to foreclose the future. We can always resist. “Two officers dreamt a lump of concrete and woke up running from their own bloody noses.”

Kemp’s poems show us a way of looking at working-class history as a weapon, not a funeral procession. Imagine that the final episode of Succession ends with a mob crashing through the windows of the Roys’ Hamptons estate and lynching the fuckers. It’s easier to do so on the back of a reading of Fortress Wapping, with its refusal to surrender to the idea that our defeats are inevitable, and its attempt to reinvigorate the possible, to imagine things other than they are by grasping fully how we ended up here.

In Cash Kemp tells us there is “…a movement turning tight with the highway and towards the glowing river”, but “there is an independence of force in either direction.” Sam Kemp’s poems remind us that the direction of history (as force, through force) can always be changed.

Fortress Wapping by Sam Kemp, £12 inc. p. and p., is available as hard copy here and as an ebook here.