An audience at Basma Theatre, now in Gaza

By Hossam Almadhoun

Culture is not a luxury but a form of resistance. – Edward Said

I was not an actor from a young age, nor did I ever imagine that this would be my path.

I had been arrested by the Israeli Occupation Forces in 1992 for writing slogans against the occupation on the walls of Gaza City. The prison was not an ordinary one with rooms and cells, it was an open yard surrounded by barbed wire and watchtowers on all sides, each tower occupied by a soldier pointing his weapon at the detainees inside.

In this yard, there were twelve tents, each designed to hold 25 people. However, it was often the case that more than 35 detainees were forced to find space for themselves inside a single tent. We slept on wooden beds raised about ten centimetres off the ground, with thin foam mattresses about five centimetres thick. The prison was located in the Negev desert. The ground was hard and muddy, turning into small pools of wet mud when it rained.

It was in this place, in these harsh conditions, that I first encountered the theatre. A group of prisoners decided to stage a play about the killing of seven Palestinian workers by an Israeli soldier. The soldier had stopped them in one of the cities under the pretext of inspection, ordered them to stand facing a wall, and then opened fire, killing them all.

The director of the play announced the start of rehearsals and asked for volunteers. In prison, time is the one thing you have in abundance, and you need to find something to fill it with. I volunteered to participate. The actors had already been selected, so I joined the support team.

We made the ropes for the stage curtain out of woollen winter sweaters. Black blankets were used as a backdrop, on which a wall from one of Gaza’s refugee camps was drawn using toothpaste. One of the prisoners was an oud player. A plastic container was provided, and another prisoner who was a sculptor carved a piece of wood from one of the beds to make part of the musical instrument. The oud strings were smuggled in by the musician’s family during one of the visits.

We arranged the beds in one of the tents to form a stage and used blankets as curtains. I don’t remember the details of the performance itself, but I clearly remember the passion and dedication of a group of detainees striving to produce a theatrical performance for their fellow prisoners.

That was the beginning. I was released at the end of 1992, determined to pursue theatre and dedicate myself to the art of performance.

Theatre as a weapon in the cultural struggle

Nowhere is the political power of theatre more evident than in Palestine, where art itself is an act of resistance.

Since the early twentieth century, Palestinian theatre has intertwined with the nation’s political and social struggles. As the battle for land and identity intensified, artists recognised that theatre could serve as a cultural weapon, no less vital than political struggle. Their works reflect daily life under occupation: a play staged in a besieged village or a refugee camp is not just a cultural event, it is a declaration that life defies occupation.

Across the Arab world, theatre has long been a space for political ventilation and dissent. In Syria, Saadallah Wannous described theatre as ‘a celebration of life and a confrontation with reality.’ In Egypt, Yusuf Idris and Tawfiq al-Hakim explored the tension between freedom and authority. In Palestine, Ghassan Kanafani and others used the stage to embody a people’s struggle for liberation.

Theatre for Everybody

In 1997 I became the Co-Artistic Director of Theatre for Everybody, which produced work around the Gaza Strip. Sometimes we performed at the Al Mishal Cultural Centre which was destroyed by the Israelis in 2018, so we then launched a program of events and workshops to continue to fund for its rebuild. There was a new funding initiative which launched in September 2023.

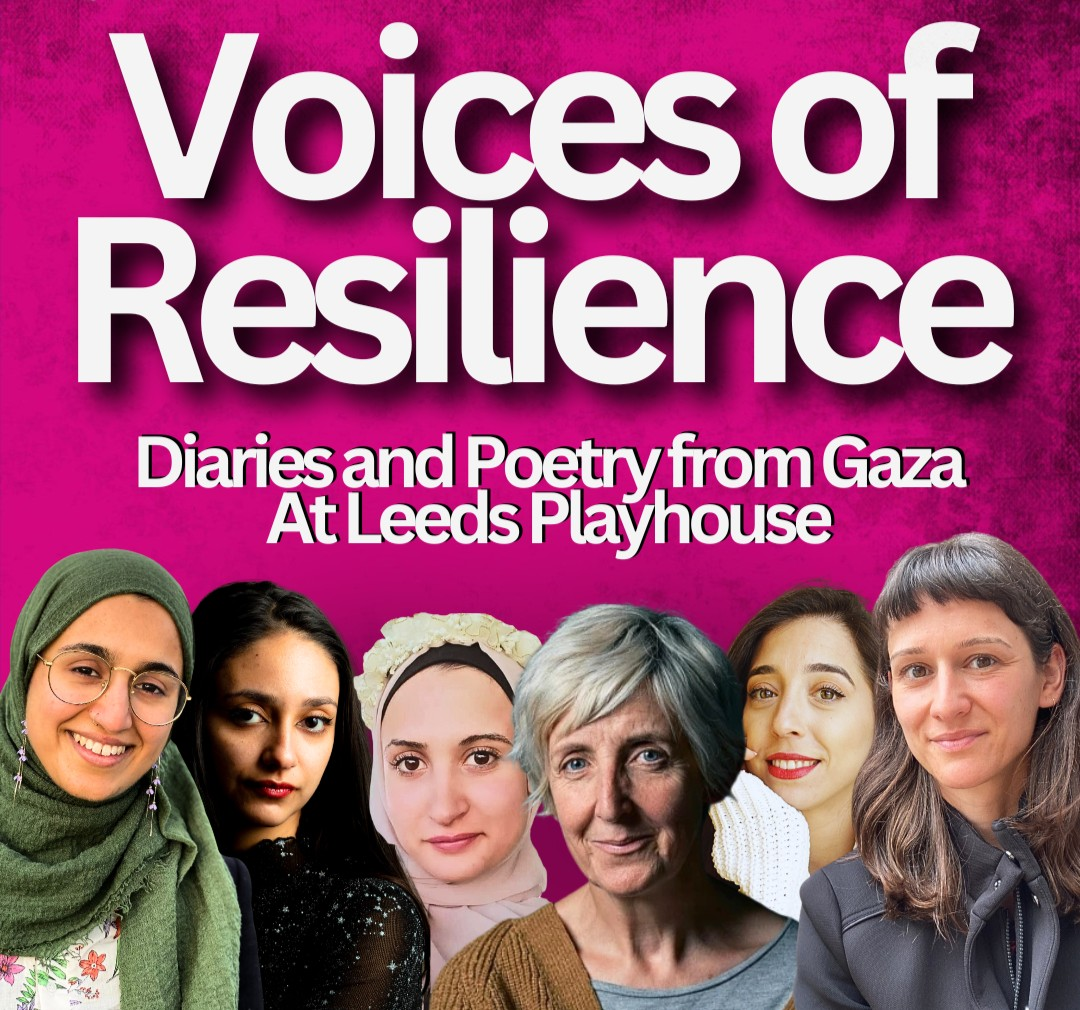

Basma Theatre, now in Gaza

From Gaza, Theatre for Everybody brought the Palestinian story to audiences across Europe through plays such as The Checkpoint, Blue Gold, and Welcome to Hell. These are plays that talked about the water rights of Palestinians and how Israel denies us access to our resources. They are plays about the blockade and its impact on people’s daily lives, plays reflecting the horror, pain and humiliation of living under occupation.

The occupation, recognising the power of art, treats theatre as a threat. Performances have been raided, actors arrested, and plays banned. For the occupier, the free word is dangerous; awareness can be more powerful than weaponry.

Yet artists persist, turning repression into creative momentum. Theatres such as The Freedom Theatre in Jenin, Al-Kasaba in Ramallah and Jerusalem, Yes Theatre in Hebron, the Palestine National Theatre in Jerusalem, and Ashtar in Ramallah and Gaza, along with independent troupes like Al-Bayader, Masafat, Basma and Fekra, have all carried art beyond performance. They have built an educational, cultural, and political project that links art, resistance, and learning.

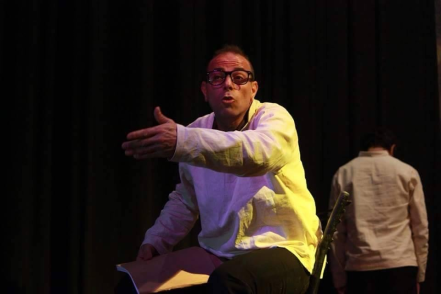

Hossam Almadhoun, Co-Artistic Director of Theatre for Everybody

It was not easy for us, especially after 2007 when Hamas took over control of Gaza, and theatre and art in general became restricted by new rules and regulations. Theatre groups were required to provide a copy of their text to the Ministry of Culture for approval; the Ministry must attend the last general rehearsal and give performance approval; then a letter to the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities should be sent asking for performance approval; then a call must be made to the tourism police to arrange a meeting where a document was signed stating that we would commit to the approved text and to the separation of men and women in the theatre hall.

All this did not stop us. We always found a way to present what we wanted to show and what we wanted to say. In 2015, immediately after the 2014 war on Gaza, Theatre for Everybody created a production of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, with a clear message that we didn’t want wars, we didn’t want violence. The play was very well received but the authorities didn’t like it much.

With huge waves of young men trying to emigrate to Europe, where many disappeared, dying at sea or murdered by smuggling gangs in the forests of Eastern Europe, we decided to produce the play The Emigrants, to warn of the dangers and to show the reality of emigration. Again, the local authorities did not approve of the play, particularly a scene where the characters were drinking alcohol. Again we persisted, put the play on, people loved it and great debates were had after each show.

As is true in many places in the world, making theatre in Gaza is not a source of secure income. I work as a child protection officer and all my theatre colleagues have other jobs. Yet we never stopped making theatre, rehearsing in the evenings, in small rooms, basements, classrooms, no production managers, no support teams, the actors and directors doing everything, and with great patience, dedication and love. Without this there would be no theatre and no political power of theatre.

Theatre in the ruins of Gaza

Amid destruction, siege, and war, theatre becomes both sanctuary and protest which rebuilds the human spirit. With formal venues destroyed, artists transform ruins, streets and tents into open stages, spaces of dignity and hope, even in the darkest hours. Each performance, whether between collapsed walls or beneath the canvas of a refugee tent, is an act of defiance, proof that creativity endures even in devastation. They remind the world that art is not a luxury, it is survival itself.

Today I live in Egypt, in exile. I have been here for a year and a half, following six months under the genocide in Gaza. I cannot make any theatre. Instead, I keep in contact with my friends and colleagues inside Gaza and they have not stopped. They use their skills, the power of theatre and art to engage people, mainly children, in drama providing education, psychosocial support and building resilience. And they and my testimonies have continued despite everything to reach wide audiences in Europe, with the commitment and compassion of a group of friends.

White Kite Collective in the UK is among these friends. They are a group of artists and culture workers that formed in urgent response to the ongoing Palestinian genocide. Since November 2023 they have shared the work of Gazan artists, writers and poets, bearing witness and galvanising audiences to action through testimony, literature and collective.

On November 8th 2025, exactly two years from their conception, White Kite Collective will present the 24th edition of Stand With Palestinians: Messages From Gaza at Theatre Royal, Stratford East. The theme of this event with be We Hunger. We Love. We Thirst: Land/Hunger/Resistance and will include some of my recent testimonies.

This work helps keep the Palestinian story alive in the face of attempts at erasure and distortion and turns the audience from mere spectators into witnesses and partners in the act of resistance.

White Kite at the Bush Theatre with Luca Kamleh Chapman, Emma D’Arcy, Motaz Malhees and Margaret Owen