All images by Jack Clarke and Max Farrar

‘Cultural democracy isn’t just a buzzword. It’s a reckoning’ says Jack Clarke

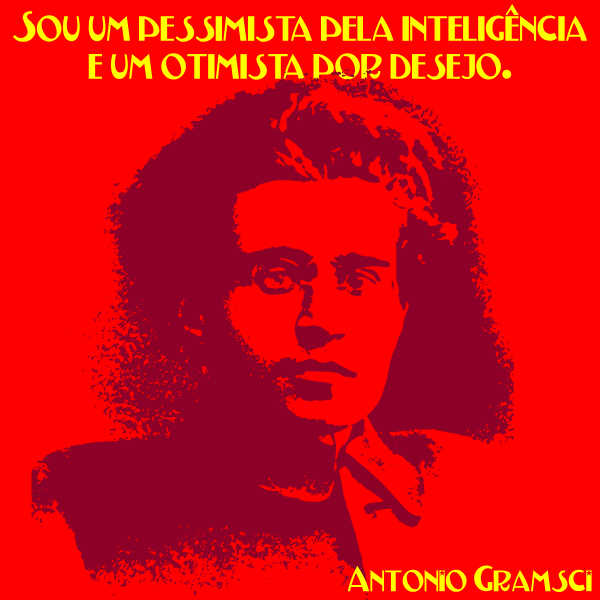

I’d barely been in the door five minutes before I clocked two uncles in flat caps arguing about the Miners’ Strike next to a girl in a Crocs-and-headphones combo, clutching a copy of Communism for Kids. Somewhere behind me, someone was deep in debate about Gramsci next to a tray of Aldi samosas. The room was buzzing. Not in the way polite art spaces hum with wine and nodding, but in that thick, living way, like something was being stirred, not served.

Welcome to the launch night of Keep The Flame Burning, the new exhibition at the Working Class Movement Library in Salford, a love letter, time capsule, and re-ignition of the radical socialist organisation Big Flame, told not by retired historians or distant curators, but by a rag-tag bunch of young working-class people, including me, who’d never even heard of half of this stuff a year ago.

Think of it like this: imagine if a Robosapien somehow became self-aware and started decoding Marxist texts. That was me last October, when I first stumbled across this project on Instagram, fresh off a three-day dopamine crash and halfway through a bag of Lidl own-brand tangy worms. The post was simple: “Big Flame archive project. Working-class young people. WCML.” I stared at it like it owed me money.

I grew up in Salford. I’ve lived here all my life. Uni, work, break-ups, breakdowns. And yet I’d never heard of the Working Class Movement Library, this beautiful, mad, overflowing archive of radical history sat literally on my doorstep, a few breaths away from where the buses break down and Greggs raises its prices every six months. How did that happen? Why didn’t anyone tell me?

Turns out, that’s the whole point.

The WCML is not just a building full of books and old leaflets. It’s a weapon disguised as a library. Built on the obsession and care of two working-class communists, Eddie Frow and Ruth Haines, who basically turned their house into a shrine for the entire history of struggle, it now lives in Jubilee House, a former nurses’ home. It looks like Hogwarts for trade unionists, stained glass windows, tall ceilings, and shelves that whisper things if you listen long enough.

When I joined the Big Flame archive project, which would eventually become Keep The Flame Burning, I didn’t know what I was walking into. Just that it said “working-class young people wanted,” and something in my chest answered back.

What followed was a year of slow, strange magic. Eleven of us, all from working-class backgrounds, meeting every fortnight, digging through pamphlets, clippings, letters and bulletins from Big Flame, a libertarian socialist group that emerged from Merseyside in the 70s. They weren’t your usual politburo lot. No Leninist cosplay, no group expulsions. Just ordinary people trying to figure out how to fight better, in workplaces, homes, streets, squats, schools, and the pages of their newspaper.

They believed in socialist feminism, anti-racism, community organising, rank-and-file workplace action, and crucially, no saviours, no vanguards, no self-important lads in beige turtlenecks acting like they’re the chosen ones.

It wasn’t perfect. But it was alive. And messy. And ours.

I used to think curation was something done to us, a middle-class job where someone with elbow patches picks which version of our past is respectable enough to put behind glass. But this? This was chaos and cheddar and long nights and sudden tears. This was us, sat around old newspapers, talking about grief and rent and Palestine and our mums. It was part study group, part therapy session, part full-body political resurrection.

We called ourselves The Little Flames, because nothing sounds more like a punk band made entirely of anxious socialists.

We didn’t just read the archive. We lived in it. We held it up to our own lives and watched the sparks fly. And slowly, something shifted. Our own memories, our nan’s photos, our cousin’s protest videos, the graffiti on the Lidl bins, started to feel like they belonged in there too.

Because here’s the truth no one tells you: we’re all curators. We’ve just been convinced that our stories don’t matter. That what we’ve survived isn’t worthy of a pamphlet or a plinth. That you need a degree and a grant and a Guardian review before you’re allowed to say, “This is important.”

Big Flame would’ve told you to fuck that. As Jason Lee, one of the Little Flames, put it:

Throughout our research there were clear parallels from organising then and now… It’s the struggle that endures as long as that flame still burns within us all.

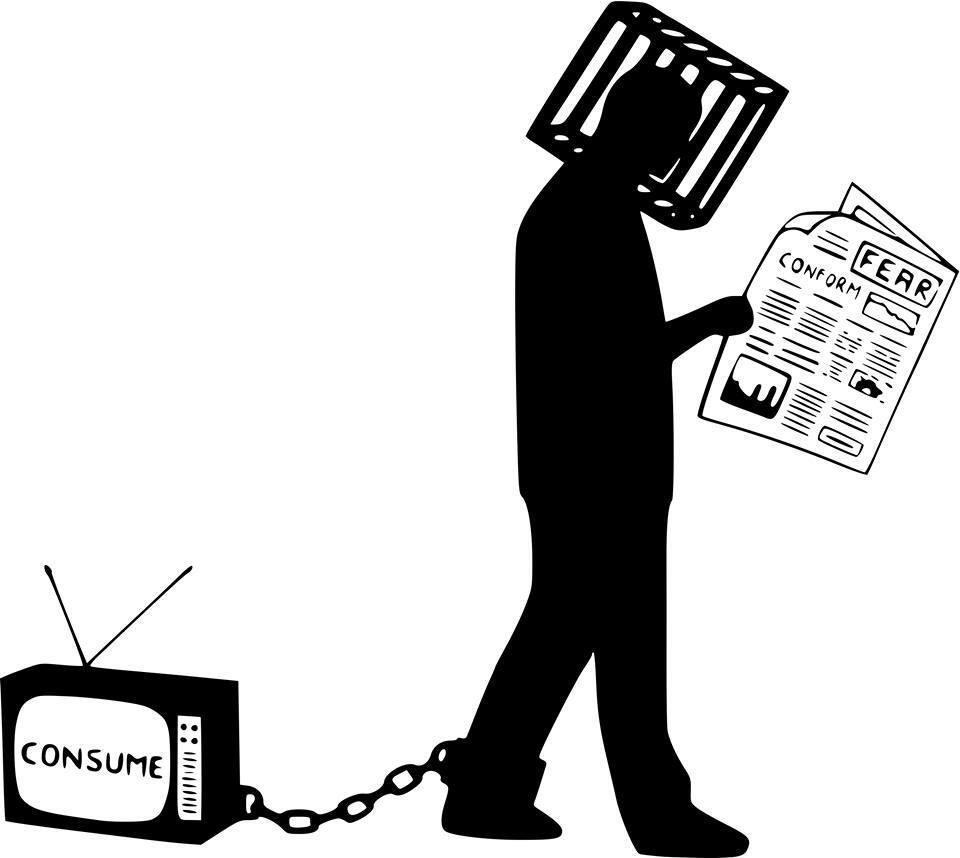

We don’t learn this stuff in school. We’re not meant to. Instead, we get the Top Gear version of British history, Churchill, Spitfires, and everything else whitewashed and weaponised. Meanwhile, Big Flame? They were out here translating Toni Negri, debating the politics of care work, and organising factory walkouts, all while housing each other in co-ops and raising hell at the docks.

They introduced Italian Operaismo to the UK, stuff that now influences activists at Notes From Below. They ran campaigns, newspapers, bookshops. They didn’t want to take power. They wanted to distribute it. And they did it while feeding each other, loving each other, disagreeing like mad but still turning up.

Their bulletins feel like WhatsApp group chats if the messages were about Marxist theory and someone’s bike getting nicked. They’re funny, sharp, chaotic, and painfully now.

Being young and politically awake in 2025 is a weird, relentless thing. You grow up knowing the world’s on fire, but being told to stay calm and sign a petition. You protest and get kettled. You tweet and get doxed. You get exhausted before you even begin.

But this exhibition, this project, reminded me that we’re not starting from scratch. We’re part of a lineage. We’ve always had more in common with each other than with the people telling us to behave.

The WCML is proof of that. A quiet, furious, generous place that keeps the receipts. And now, through Keep The Flame Burning, we’re adding to the pile.

It’s not a throwback. It’s a relay.

So yeah, maybe your uncle still thinks socialism means queueing for bread. Maybe your neighbour’s convinced Labour’s too “woke” to win. Maybe you’ve never stepped foot in a library since Year 9 isolation. I get it. But hear this: this is ours. This project is proof. Working-class people aren’t just subjects of history, we’re the authors, editors, printers and typesetters too.

Cultural democracy isn’t just a buzzword. It’s a reckoning. When you give people the tools to tell their own stories, the whole script changes. And what we’ve built with Keep The Flame Burning isn’t just an exhibition. It’s a declaration.

We are the memory keepers. The curators. The critics. The builders.

And we’re just getting started.