In this instalment of Our Culture, we explore the contradictions at the heart of one of the world’s most profitable and precarious creative industries: video games. Scott Alsworth, an award-winning developer and member of the IWGB Game Workers union, reflects on the current crisis facing game workers and the emerging class consciousness within the industry. From the “live service trap” to union busting at Rockstar, Alsworth lays bare the exploitative practices of global capital as they come about in the production of video games. In the follow up questions by Series Editor Alan McGuire, Alsworth digs deep into how socialism could begin to transform the industry.

The videogame industry in the UK, and indeed, all over the globe, is in a state of contradiction and transformation, as the internal logic of capital reconfigures its economic foundations, its means of production, and the very cultural superstructure it produces. Workforce automation through AI, the post-Covid slump in sales of interactive entertainment, autocratic management structures, reckless over-investment and consolidation, spiralling development costs, rising interest rates, high inflation, cuts to cultural spending, market saturation, the so-called “live service trap”, and the boom and bust dynamics of capitalism itself, have led to a perfect storm of immiseration for game workers everywhere. Studios are closing left, right, and centre. In the last 18 months alone, more than 1,300 skilled jobs have been lost nationally. Moreover, with these redundancies, staggering violations of UK labour laws are occurring, with millionaire tech-tycoons attempting to silence and intimidate whistleblowers. Non-Disclosure Agreements are being weaponised and trade unionists victimised, with scores unfairly dismissed from Rockstar in one fell swoop.

Currently, only a fraction of game workers consider themselves working-class. The reasons for this imbalance are as complex as they are long-standing. Aspiring developers from poorer backgrounds are held back by informal gatekeeping, cronyism, sexism, racism, ageism, high-level sinecures for friends and spouses, university tuition fees, the cost of specialist courses, and the prohibitive expenses of getting into gaming in the first place. Additionally, for those who make it into the business, toxicity and prejudices regularly await. The grotesqueries of Hollywood’s “casting couch” culture have made their way to the sector, as have cults of personality. That 31% of game workers have also admitted to depression and anxiety or both, isn’t at all surprising. Cases of burnout aren’t uncommon. This is predictably caused by long periods of “crunch”. That is to say, unpaid overtime. This can last for weeks, months, or even years. During particularly chaotic periods, game workers may be compelled to work without sleep. I can attest to this from experience, having once pushed through a 96 hour stint. However, it’s important to note the myriad problems blighting the industry aren’t solely “industrial”. There’s also a creative struggle going on. A “war of position”, which, even if it’s not generally recognised in Gramsci’s terms, is finding expression.

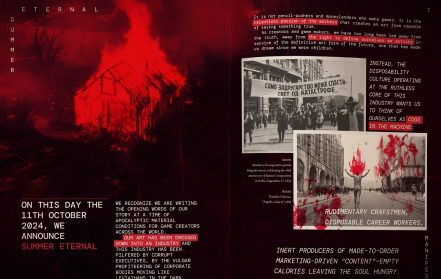

The apocalyptic conditions affecting game workers today are certainly garnering attention, but what’s less often observed is the quiet consolidation of a leftist, counter-hegemonic bloc. Individuals and groups of individuals are now coming together as conscientious artists and organic intellectuals to fix the world with a grievous eye. To disrupt capitalist realism and its tenets of anti-intellectualism, historical revisionism, fungibility, interpassivity, and depressive hedonia. To oppose the influence of “militainment” and outpace the tendencies of the far-right, who continue to use gaming circles for recruitment and the dissemination of extremist ideas. Behind the open letters and picket lines, the protests and days of action, there is another battle raging. One for the truth, integrity, and the social import of art itself.

AM: Can a new generation of game developers become the “organic intellectuals” of our time, using art and stories to challenge capitalist realism and the far right? Do we need to just push more progressive storylines or is there more to it than that?

SA: These are very salient questions, and both are central to any discussion on a Marxist tendency in videogame development. The “organic intellectual”, as defined by Antonio Gramsci, is well-situated to instigate revolutionary change in the culture industry, although they might not necessarily use art and stories. Methodology is rather less important than the lived experience and class consciousness of the organic intellectual themselves. It’s not enough for a videogame developer to be a Marxist in these terms. They must actively strive through videogame development to reshape society.

This is impossible for “traditional intellectuals”. They can never feel without feeling, or know without knowing. You can’t really think in life unless you’re participating in it. The responsibilities of the thinker are something we have to encounter first-hand, as a permanent persuader. Indeed, a dilemma we have today is that academics with no actual background in making games are educating students in game studies. Not only are the latter woefully unprepared for entry level positions on graduating, they are taught that videogames are just that, video games. This narrowing of the medium, as a kind of play-first, bourgeois formalism, is then perpetuated and compounded.

So, I mean, if we want to know whether a “new generation of game developers” can become the “organic intellectuals of our time”, we probably ought to ask ourselves: what informs that shift?

Interactive entertainment is an enormous echo chamber, promoting the status quo. And that is to be expected. As Marx put it: “The ideas of the ruling class in every epoch are the ruling ideas”. Yet we might question what the conditions are that lead us to see ourselves as active agents in the class struggle. Here, it makes sense to examine the ways in which capital races pell-mell to accumulate ever-greater profits through new and emergent technologies. In so doing, workers are inadvertently proletarianised — for example, through AI-driven job displacement — and empowered, especially by co-optable ecosystems and freeware.

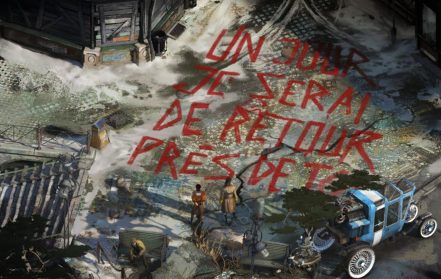

This is, perhaps, to lean a bit too much towards vulgar Marxism; let me add, I’m of the opinion art and stories are the sine qua non in counter-hegemonic potential. Readers aligned with Theodor Adorno and the Frankfurt School will have a different view, I assume. And that’s absolutely fine. There’s space for negative dialectics in the Marxist videogame, just the same as there is for socialist realism, or a Brechtian “epic ludology”. For my part, I’m with the Austrian poet and art theorist, Ernst Fischer. That is, I believe art should be social and that form follows content. The efficacy in this approach is self-evident in titles like Disco Elysium.

Regarding whether we need to “push for more than progressive storylines”, the answer is “yes, most assuredly”. A videogame studio is a lot like an orchestra. Narratology might be the entirety of the string section, and while it could carry a leitmotif on its own, or strike up antiphonies between, say, its violins and double basses, it would be a reductive limitation. There are many disciplines that come together in a videogame. It is the ambitious Gesamtkunstwerk, or “universal artwork”, once championed by Wagner. A true Marxist tendency in videogame development must inevitably pervade every part within the whole.

In other words, we need to interpret not only narrative design and game writing through a radical lens but art, gameplay, music, audio, voice over, cinematics, marketing — the list goes on.

AM: Gaming and unions are not normally seen in the news together but recently there have been reports about Rockstar and union busting. Could you tell us a bit about it and is this a common problem?

SA: The situation over at Rockstar is without a doubt the single most egregious attack on union activists in the history of the videogames industry. As a member of the IWGB Game Workers elected committee, liaising with those affected, it’s an especially emotive issue. Over 30 employees have been fired without warning, without the option of accompaniment, and without any evidence of wrongdoing. All because they chose to exercise their legal right to organise for fair pay, better conditions, and job security. We have members who are about to lose access to vital medical treatment afforded by their employment healthcare, as well as some who will soon have to leave the country because they were here on visas.

Meanwhile, Rockstar is telling the press that these workers were dismissed because they were leaking confidential information on a public forum. This is not correct. The forum was private and restricted to union organisers and Rockstar employees, who had just reached the threshold for union recognition. The company’s aim was union busting, through and through. To me, it almost feels like someone decided to take a page from Donald Trump’s playbook, testing UK labour law with a decisively ‘might is right’ business ontology. That’s speculation on my part, but still. Rockstar’s actions are a concern. Not because they’re a ‘common problem’ per se, but because they are at risk of becoming one. The danger is that this behaviour is accepted as the new normal. That we lose our capacity to be shocked. And with that, our ability to resist.

It’s probably worth mentioning here that Rockstar, a child studio of a US-based conglomerate, are also the primary beneficiary of the UK’s Video Game Tax Relief. To date, they’ve claimed over £433 million from this public subsidy, which was meant to encourage growth and equity across the nation’s game development scene. More galling is the fact that Rockstar’s next release, Grand Theft Auto VI, will likely see profits above £10 billion. This, then, is not some small indie outfit requiring financial assistance. This is a corporate behemoth which needs regulation, which needs to be held accountable by the state.

AM: With computer games so widespread, can you see them becoming even more mainstream than movies and TV? Obviously this would raise the stakes for the left today.

SA: Indeed. Although I would argue the stakes are already raised.

Economically, videogames significantly surpass film in the mainstream and are rapidly catching up to revenues generated by television. At the moment, the global games industry is worth something like $215 billion annually and set to increase to about $400 billion by 2030, with year-on-year growth outpacing all other sectors at around 5-10%. In comparison, box office sales peak at $40 billion and television has flatlined at $600 billion. For a little extra context, videogames are worth more than music, theatre, the visual arts, and cinema combined. Half the planet are playing videogames and the other half are likely to join them by the middle of the century. Clearly, we’re not where we were decades ago. The landscape is transforming fast and the left needs to get to grips with this new reality.

From a strictly “cultural” perspective, things are a bit more nuanced. Yet, we can’t deny videogames are making a splash. They’ve become a trans-platform phenomenon. There’s a steady stream of popular television shows and films and books, all based on digital play. You have Esports too, which are beginning to rival viewership for traditional sporting events. You might not like it but the way we interact with culture is changing. Governments and militaries are, of course, acutely aware of this. It’s why the UK’s armed forces are investing substantially in “militainment” and the fascist administration in the White House are sharing memes on social media of Donald Trump wearing armour from the hit first-person shooter, Halo.

A highly influential historian and ludologist once observed that “civilisation is played”. I’m not sure I completely agree, but it’s certainly evident that play permeates culture.

AM: How could a future left government change the videogame industry around public ownership, fair pay, and democratic control?

SA:To start with, I suppose you’d want to decommodify play and seek out non-commercial alternatives to existing for-profit models. There’s plenty of precedent for this. Take the early days of the BBC, for instance. I could easily imagine a generous state mandate for videogame development, ensuring educative, artful, experimental, and above all, social content. Such an enterprise might also be more inclusive. According to a recent survey, only 13% of game workers identify as working class. By ending corporate ownership and introducing free education, we’d have a chance to alter the industry from below.

With this, you’d have to establish some kind of virtual, democratically-controlled public infrastructure to replace digital storefronts like Steam, Epic Games, and various app stores. With government funding, the platform could do away with extractive fee structures. Presently, it costs $100, or approximately £79, to publish a game on Steam, and while that’s not a prohibitive sum, as a distributor, the company also takes a 30%t cut from developer proceeds, which can make a pretty big difference for smaller, leaner studios. I guess a related issue that requires attention is “discoverability”. Newly published videogames seldom get the visibility they deserve and are frequently missed by consumers. To get around that, you could put a stop to paid advertising and redesign recommendation algorithms, using a transparent metric to prioritise values beneficial to society. Other possibilities might involve regional videogame festivals, online “ludic libraries”, democratic curation, or thematic spotlights to showcase progressive subcategories.

As for “fair pay”, that demands a legal remedy. The IWGB Game Workers union have done a great job addressing this in their manifesto and, honestly, I’d advocate along similar lines: stamp out unpaid overtime, close the gender pay gap, and enshrine royalty rights in law.

When it comes to democratic oversight, I’m ambivalent. Controlling distribution is one thing, creative processes and methodology, quite another. That might seem exclusive, but I’ve seen art by committee and it rarely works. That’s not to say studios run as cooperatives are doomed to failure. Far from it. I only mean that they depend upon a special sort of in-house “chemistry”. You need a development team that’s magically in tune. For anyone interested, I would point towards a recent start-up, Summer Eternal. They’re currently pioneering a cooperative structure and are even offering shares to players. It’s an exciting initiative, to be sure, and a good reminder that we don’t have to wait for a left government to exercise cultural democracy.

AM: What concrete steps could unions, cooperatives, social movements, and political parties take now to build a fairer, more sustainable videogame industry?

SA: Obviously, unions are at the forefront of this struggle. Everything they do is a “concrete step” in the right direction. Building for a “fairer, more sustainable” future is, as you’d expect, their raison d’etre. Given this, it’s probably best to reframe the question slightly to focus on strategy. Labour organisations need to carefully map the sector through workers inquiry. We need testimonials, mass anonymous surveys, and reliable data on hierarchies of exploitation. To borrow again from Gramsci, if we relate this to a “war of position”, we have to have an understanding of our terrain. It’s no good fighting in the dark.

Likewise, we must also restore a strong sense of collective working-class identity — and that’s something cooperatives, social movements, and political parties can help with. The problems we’re facing are political and require a political solution. We can’t afford to slip into that “trade union conscious” Lenin writes of. Instead, we’ve got to educate ourselves and participate in class-for-itself not class-in-itself action.

Another measure these groups could take would be to reform the UK Video Game Council. This C-suite advisory panel, purportedly working in partnership with the government to support growth, innovation, and the international reach of British videogames, has no rank-and-file workers, no grassroots charities, no diversity associations, and no unions. Regional representation is similarly lacking, with members predominately hailing from companies located in London and the south. By protesting, petitioning, and raising public awareness, we could maybe persuade the Department for Media, Culture, and Sport to call for a reassembly of the board with a broader cross-section of industry voices.

In the end, we’ll need legislation to turn things around. Our unions can win us concessions, but the crisis we’re in is systemic and ultimately caused by capitalism. If we’re serious about protecting game workers from AI, wage theft, unemployment, mismanagement, résumé parsing, labour-intensive assessment tests, or any other number of grievances, we must win political power. Socialism has to be the endgame.

Be sure to read the other articles in the Our Culture Series:

Culture as Class Struggle: An Interview with Jenny Farrell

Our Culture: RIP British Working-Class Cinema (1935 – 2025) by Brett Gregory

Our Culture: The Uncomfortable Truth About Public Libraries

Our Culture: Breaking through the Class ceiling with bread and roses