In this edition of Our Culture, we turn to the prison system, one of the most hidden yet culturally rich spaces in Britain. Often seen only as sites of punishment and exclusion, prisons also generate powerful creative work, from poetry and rap to sculpture, painting, and model-making, produced under conditions of isolation, deprivation, and control. Poet, former prisoner, and regular Culture Matters contributor Nick Moss argues that culture behind bars is not art for art’s sake but a form of resistance, a way of reclaiming humanity within institutions designed to strip it away. Later, in conversation with Our Culture series editor Alan McGuire, Moss explores creativity as self-definition, the contradictions of rehabilitation, and the class and educational structures that mean prison is often where working-class people first encounter their creative selves.

Most people who’ve not been banged up will probably be surprised to know that prisons are thriving centres of culture. Prisoners make models in extraordinary detail from matches and sculpt fantastic creations from soap. Prison arts classes will uncover cons who can produce beautiful pencil sketches of friends they’ve made on the wing, or spice-aided abstractions in fantastic colours. A friend of mine produced elaborate glassware while doing a long sentence for Irish “terror” offences. Another made pottery which incorporated various anarchist texts in the design.

The Koestler Prize exhibition is annually full of artwork produced by prisoners from probably every jail in the UK. Prisoners also write plays and act in drama workshops. I wasn’t the only poet on my wing. If you read Inside Times you’ll find that prisoners produce a monthly printed newspaper, and that it features a hell of a lot of prisoner poetry.

Poetry is a way of inventing concepts that help us make sense of the experience of jail. It means that many people who wouldn’t have considered themselves likely to ever write poetry, suddenly experiment with words to capture, consider and communicate their experience of imprisonment. The jails of the UK host or have held some of our most gifted rappers. Mazza L20 became known first of all through sending out jail freestyles that were then posted up on YouTube. Wesavelli has done the same.

Because of the life they’ve lived inside and out, both men bring a deep hurt and rage to their bars, and a level of rhyme skill that comes from having fuck all else to do but practice and keep getting better and better. Other jail freestyles worth seeking out are from Big S, X3, Lemz, BZ, and J1. All of these are full of real pain and incredible wordplay.

The development of artistic practices in jail is a direct form of resistance to the attempt of the prison system to dehumanise prisoners. Prison dehumanises by default even where it does not do so by design. In that sense, the direct, often physical, oppression of the high security estate is merely transposed to a different mode in the Cat D estate-the administration of human beings as numbers remains the same.

Culture and creativity are means of resistance. I remember hearing about a high-profile prisoner from Manchester who was fucked over by some money-hungry screws who sold a story to the tabloids about him being allowed to paint a picture for his kid in an arts class. This con’s offence was non-sexual but still grim – but the prison system was determined that he would be allowed no humanity even while purporting to offer rehabilitation. All he would be allowed to be was the worst that he’d ever been. The fact he could be more than that offended not only the screws who sold his story, but the system designed to keep him as he was.

And here’s the big question – if cons can create fantastic art, great music, study for doctorates while in jail – what kind of education does capitalism offer to working-class kids if we discover our potential only in trying to define ourselves against prison-manufactured alienation? Prisons are the warehouses we are dumped in after the education system has already failed us.

AM: You describe prison creativity as a form of resistance against dehumanisation. Do you think this creativity changes the way prisoners see themselves, or is it more about showing the outside world that they can do something else?

NM: I think it definitely changes the way prisoners see themselves. One of the things I think is particularly important is that right up until we are sentenced and driven away – and often afterwards with press reports, family expectations, offending behaviour requirements etc, we lose all control of the narrative about who we are and how we came to be where we are.

Finding a creative voice allows us to challenge that narrative, a) by doing something no one (usually including ourselves) ever thought we were capable of and b) constructing our own narrative about who we are and how we ended up where we are. You’d anticipate that there’d be some degree of self-romanticisation in this and that can be true initially, but the thing is, you know yourself if you’re bullshitting or capping, and that is a bit of a futile exercise given where you are. If you take Mazza L20 as an example – he honed his craft in jail and is now making a major name for himself outside, and he’s able to deal with all the pressure of that because he’s already looked hard at who he is and has defined himself through working through a fairly brutal self-examination that’s sketched out in his lyrics:

I grew up in the system

Your granddad, your nan and your uncles, I missed ‘em

But prison breaks bonds and makes the ones you love distant

And now relationships are different

Your mother kept it real for me, she always sent pics in

It wasn’t easy, could’ve broke like a victim

I got shot and had a couple operations in Whiston

Wise men can play a fool, I’m just tryna give you wisdom

Started rapping in a cell, tryna blow like a piston

They always tried to break me down, I always showed resistance

Prison officers used to tell me, “Stop resisting”

But I guess what I’m tryna say is always be persistent

Practice makes perfect so you’ve gotta be consistent

(Mazza L20 –Letter to my Son)

I think at the core of working-class artistic practice, in jail or outside, is developing a different kind of subjectivity to that which is the norm in capitalist society. I think part of becoming a class-for-ourselves is becoming individual subjects — for ourselves in a way that sees us having potential beyond the boundaries and wants that are the limit points of life under capitalism. Prison is somewhere that creativity can be honed as resistance simply because we are told that we are capable of nothing and fit only for being banged up 23 hours a day.

AM: The cultural examples you give (poetry, rap and matchstick models) are part of prison world that most people never see. How do you think these cultural acts could be better connected to society beyond the prison?

NM: It’s not easy to answer that. I think it would be good for the left to engage with issues around prisoner solidarity more generally and to encourage prisoners to contribute letters, articles, poems etc. Inside Times is a good place to start to get an idea of the issues that impact on prisoners and to work through what the left might offer by way of solidarity.

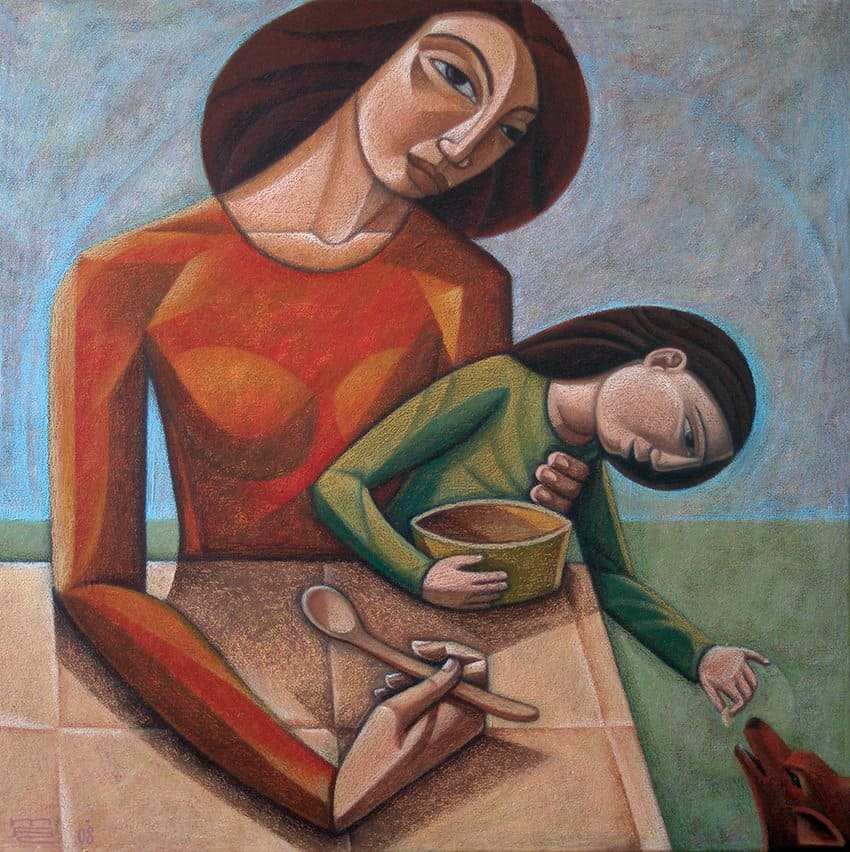

I also think that there’s a need to make an effort to look at the works highlighted by the Koestler Trust in their literature and exhibitions, and Prodigal Arts (which supports offenders and ex-offenders to exhibit and sell art) and draw attention to their work. I think that prison and post-prison rap is something worth seeking out (YouTube and Spotify) and critically engaging with. If someone is talking sexist bullshit but otherwise breaking down quite effectively how the systems of exploitation we’re caught up in actually work, then call them out on it! If artists are targeted, mobilise to support them. Fair play to Kneecap for sticking their necks out on Palestine — but you’ll see drill rappers threatened with recall for something said in a lyric and we need to be showing support to them too – especially where they’re trying to highlight how the police come down on their communities.

AM: You describe how the system tried to deny a prisoner the chance to paint for his child. What is the tension between rehabilitation and punishment in prisons today? And is it different to the wider public opinion?

NM: The Prison Rules 1999 at paragraph 3 state that “The purpose of the training and treatment of convicted prisoners shall be to encourage and assist them to lead a good and useful life.” This begs the obvious question – a “good and useful life” for who? The prisoner or society in general? What does a good and useful life actually mean? As it’s undefined, it can change from minister to minister, never mind government to government. What this means is that the contradiction between rehabilitation and punishment is one that runs through every aspect of prison life.

If you really wanted to give everyone a fresh start you’d provide wraparound care and support – fully-funded drug rehabilitation programmes, post-release housing, continuous educational development while inside. In reality, these are the kind of things that get cut first. In Belmarsh, the work available for prisoners when I was there, was either smashing up DVD cases or assembling prison breakfast packs. Really constructive work! Prison wages have this year gone up by £1. As Inside Times explain:

The last time prisoners saw a pay rise was in 2016. Since then, an eight-year pay freeze has seen their purchasing power decline, as prices of goods on weekly canteen sheets has risen with inflation. According to the Bank of England, someone on a typical prisoner wage of £15 per week in 2016 should have seen the sum grow to £20.15 per week by 2024, just to stand still. By that measure, a typical prisoner has suffered a real-terms pay cut of 20 per cent in eight years, even taking the £1 rise into account. (Inside Times 3 February 2025.)

Moreover, the Incentives and Earned Privileges Scheme which determines the kind of daily regime prisoners are held under – whether they’re allowed a TV, how much time they get out of cells etc is designed to encourage uncritical conformity and punish resistance. I don’t believe prison is intended to have a rehabilitative purpose. It’s simply a smokescreen. This isn’t to deny that there are people working in jails who genuinely want to make a difference – it’s a systemic issue.

If you wanted to address the issues that derail prisoners’ lives, you’d have to look honestly at the problems of class, race and gender inequality that underpin all this – and prisons are not designed to do that. They’re simply warehouses for the poorest and most damaged in our society. There’s also, in relation to rehabilitation, the issue of what to do about those of us who are simply unrepentant, and it’s clear that the serious disruption and prevention order in the 2023 Public Order Act, and the serious violence reduction order in the Police Crime Sentencing and Courts Act 2022 were moves towards generalised control orders to proscribe specific anticipated forms of resistance, and that the Starmer government will only continue down this road.

We’re at some point, I’d guess, likely to see the resurrection of IPPs but in relation a) to political activities and b) to purported organised crime where there isn’t sufficient evidence to nail a multitude of people on a conspiracy charge. I note as well that there are elements of the left who are pushing for Starmer to make quick law and order policy gains as a way to head off Reform. This assumes that the majority of voters accept the Farage assertion that “Britain is lawless.” I think most peoples’ daily experience is in conflict with this, and we have a duty to not run with a convenient fiction instead of relying on facts.

I think as well that some on the left forget that most working class peoples’ views on law and order are contradictory and that it’s the contradictions that matter. Someone can be outraged when his tools get nicked from his van, but also have a mate who has been banged up unfairly, and have bad experiences with the police either at the football or via stop and search etc.

AM: You make a powerful statement at the end: why do so many people only discover their potential in prison, after the education system has failed them? What changes in education would prevent that downward cycle that many fall into? Or is it something beyond schools too?

NM: I think education as a resource has been consistently underfunded and turned towards instrumentalised learning for a future of either low-paid service work or work around AI and programming. I guess most teachers’ idealism dies in the face of oversized classes and a rigid curriculum that does little to encourage critical thought.

Capitalism doesn’t need critical thinkers. I think the experience of having a generation of working-class kids go to university in the 50s and 60s and the end result being 1968 and the years of revolt and rank and file action thereafter, probably taught it a lesson there.The US educationalist Henry Giroux once said:

Schools should be democratic public spheres. They should be places that educate people to be

informed, to learn how to govern rather than be governed, to take justice seriously, to spur the

radical imagination, to give them the tools that they need to be able to both relate to

themselves and others in the wider world. I mean, at the heart of any education that matters, is

a central question: How can you imagine a future much different than the present, and a future

that basically grounds itself in questions of economic, political and social justice? (Henry

Giroux-America on the Edge 2006)

If you think of how far we are from that, then you can see what the problem is.

Read the rest of the editions from the Our Culture series:

Culture as Class Struggle: An Interview with Jenny Farrell

Our Culture: RIP British Working-Class Cinema (1935 – 2025) by Brett Gregory

Our Culture: The Uncomfortable Truth About Public Libraries

Our Culture: Breaking through the Class ceiling with bread and roses

Our Culture: Games and Class Struggle – with Scott Alsworth

Our Culture: Prize-winning Poetry Only Please! with Andy Croft