A Few More Sunrises Yet Before It Ends – Selected Poems by Martin Hayes (Broken Sleep Books, 2025), 359pp

By Alan Morrison

A Few More Sunrises Yet Before It Ends comprises selections from five of Martin Hayes’ previous poetry collections: When We Were Almost Like Men (2015), The Things Our Hands Once Stood For (2016), Roar! (2018), Ox (2021), Underneath (2021), and Machine Poems (2024). Most of those volumes are of considerable size in themselves so Hayes and Broken Sleep Books’ editor Aaron Kent have clearly done some extensive sifting of material to get this Selected down to the 359pp page mark.

For anyone familiar with the oeuvre of American blue-collar poet Fred Voss (1952-2025), his rangy-lined free verse depictions of manual factory work have served as something of a template for the unpunctuated expansions of Hayes’ poems, almost all of which are based around his place of work, a courier firm in London. But while Hayes might be seen as the UK’s answer to Voss (he too shares a tendency for long Whitmanesque poem titles), he has through the course of several volumes stamped his own signature on the underrepresented poetry of employment.

One key difference to Voss is that Hayes depicts his experiences in the courier industry where he works as a computer-clamped ‘controller’, more white-collar than blue-collar work, though arguably much more precarious. As Andy Croft notes in his Foreword, the corporate sweatshop of Phoenix Express is a computerised contemporary replacement for the exploitative painting-and-decorating firm Rushton & Co. in Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists (1914).

In Ox, the poem ‘Ox and the Great Big Identity Trick’ echoes the key Marxian concept of ‘The Great Money Trick’ as presented by the Tressell’s main protagonist, socialist sign writer Frank Owen, who fruitlessly tries to awaken a class consciousness among his complacent, tabloid-sated workmates. Thematically there are also echoes of Jack London’s semi-autobiographical blue-collar Bildunsgroman, Martin Eden (1909).

Croft touches on other similarly-placed poets in his Foreword: ‘In the first half of the twentieth-century a number of self-taught working-class poets emerged from the urban proletariat to write about their part in the productive labour-force – notably Joe Corrie (the Fife coalfield), Ethel Holdsworth (Lancashire cotton-mills), Julius Lipton (East-end sweatshops) and Fred Boden (the Derbyshire coalfield).’ But this proletarian tradition in literature stretches back to the 18th and 19th centuries much of which mushroomed from the Chartist movement.

Hayes’ job title of ‘controller’ is ironic given the poet’s sense of employee powerlessness, as he puts it in ‘In Between Controlling Jobs’:

in between controlling jobs

we sit dumb-open-mouthed

staring into the carpet

for hours

we look Hell in its eyes

trying to find a position for the uselessness we feel

that we have become

and then the moment we get employed again

we begin to feel our blood

Phoenix Express employees are the daily prey of their very controlling supervisors:

the telephonists come in with dead faces and tired eyes

saying yes to everything their supervisor says

just so they can get rid of her

and get back down to working out how much a month they can afford

to spend on Janey from accounts

Littlewoods catalogue.

‘Dead Faces and Tired Eyes’.

Exploitative and negligent, these supervisors only seem to supervise but do little else:

and no supervisor has ever thought

of actually replacing the faulty keypad

because that is not in the rationale

of the company

it is also no good for any of us controllers

to suggest it

because that would just be considered

make believe

and single you out

as a troublemaker

(‘How To Be Get Singled Out As A Troublemaker’)

Then there is the monitoring made by ‘programmers’, as detailed in ‘Trying To Paint The Sistine Chapel Over Again’: ‘all the while writing down notes in their little Moleskine books/ that will apparently help them/ hone their monster’. Further into this poem, Hayes launches into a lyrical tangent as to how the supervisors didn’t understand the complexity of ‘this controlling lark’ as if they had they wouldn’t have ‘signed off on a new automated allocating system/ that goes live next week…

which won’t be able to paint the Sistine Chapel over again

which won’t be able to leap like a Nureyev

which won’t be able to carve marble like a Rodin

and which won’t be able to see the unseen

or think the unthinkable

quite like us human controllers can

This is a powerful comment on human imagination and creativity which cannot be substituted by technology or AI. Yet in spite of their strictly monitored and controlled working environment, there’s a sense of overall aimlessness: ‘someone somewhere at Phoenix Express/ must know why and what they are doing/ even if we don’t’ (‘Futility’).

This constant surveillance in the workplace reminds me in some ways of the Public Control Department in Wilfred Greatorex’s dystopian drama series 1990 (1977-8), although that is ostensibly set in a near-future ‘socialist’ dystopia—Phoenix Express is the product of our hyper-capitalist society, where corporations do much of the monitoring, so more a Huxleyan than Orwellian dystopia.

There is a sense of class tension in many of the poems, particularly in the sardonically titled ‘The Importance of Law and Medicine’, which describes dilettante interns drawn from upper-middle-class backgrounds: ‘many of the sons of these great men/ leave by the end of their first week/ and go off to “do” India or “do” Thailand’. Episodes such as these bring to mind early twentieth century scenarios of stratified clerkdom as depicted in novels like J.B. Priestley’s Angel Pavement (1929) or sociological studies such as David Lockwood’s The Blackcoated Worker: A Study in Class Consciousness (1958). It’s as if the brief pool of social democracy and post war consensus between 1945 and 1979 never happened.

A particularly powerful poem is the short and despairing ‘Terror Street’:

…why must we sit in armchairs

sipping at dead wine in half-dead dark?

why must we walk through parks looking up at the sky

feeling nothing?

…why must we believe in protecting our jobs

when the sea

doesn’t believe in anything?

‘Last Rites’ depicts a 53 year old employee ‘laid off’ due to his age and possibly flagging performance, gifted a ‘collection’ in a ‘manila envelope’ along with ‘the hurt and utter uselessness/ they try to block out’. The Hemmingwayesque-titled ‘The Sun Didn’t Rise Today’ poignantly addresses a colleague’s suicide and closes another colleague’s apothegm on the subject:

Ronnie

commenting later that,

“some men

are just far more capable

of doing almost anything

than other men

I guess”

There is something of Hemmingway’s ‘iceberg’ sensibility to Hayes’s poetry: a sense of much more beneath the surface which isn’t actually said. This also fits with the masculine character of Hayes’ work, or at least, societal notions about masculinity as synonymous with emotional inhibition. Hayes’ verse is also very visceral, with anatomical images frequently featuring, particularly ‘blood’ and ‘teeth’. Hayes physicalises employment as something sinuously oppressive, full of muscle: ‘the the company that these hands work for/ try continually to devise ways to detach these hands from the rest of him’ (‘These Hands Have Made Sandcastles Too’).

‘We Help These Corporations Exist As Our 83-Year-Old Mothers Remain In Pain’, which could have been a song title by The Smiths, or The Housemartins for that matter, is similarly visceral in its anguish: ‘we help these corporations exist/ as we work through toothache/ work through hangovers/ pumping away at our keypads’.

These poems from Hayes’ second collection show a more figurative poetic sensibility coming into play which makes the polemics all the more effective:

they are under interrogation our fingertips

are on the run they are

scratching at the earth

trying to make the tunnel big enough

so that everything else behind them can follow

our fingertips are the pickaxes of their Gulags

their owners sit in rows

tapping away at their keypads

these owners who haven’t owned these fingertip

for years

for centuries

made to feel guilty that their fingertips are alive

made to feel ugly that their fingertips are unique

when they should all just be mucking in

part of their collective

with this company’s heart as their heart

with this company’s blood in their blood

our fingertips who have no other way to exist

other than this way of theirs

who never get to share in its profit

but who always seem to get to share

in its losses

(‘Our Fingertips’).

These moments of more figurative language give pausing points of lyrical grace amid the mundane and grittier detail—and they often come as crescendos at the close of poems: ‘filled with other men all seeking the same type of peace that eagles gliding/ through the immense sky feel’ (‘Peace’). In Roar!, there’s a poem titled ‘Lifting Off Like Eagles Into The Sky’ to describe the elation of Friday afternoons: ‘as Stevie sat back with a big Cheshire-cat grin on his face/ rubbing his hands together in anticipation so fast that smoke rose up from the palms of his hands’. It ends on a perennial epithet for employment: ‘some men/ will just never understand/ what a Friday afternoon means/ to other men’. In ‘That Uncontrollable Pit of Debt’ there is the line: ‘you can feel the anticipation/ in your guts/ the warmness kindling’.

Amidst the dehumanising environs of the courier trade Hayes never misses the moments of black humour:

the mechanics outdid even themselves

on their latest beano down to Southend

with Scott not even making it there

detained at Loughton services

for pissing in a rubber plant next to the Cashino one armed bandits

This poem, ‘Beano’, closes on the ironic trope: ‘nothing though/ that a day out at the seaside/ couldn’t put right’. ‘The Employed Poor’ makes its point in an almost concrete poetic descent on the page, rather like an iceberg (Hemmingway again) beneath the surface, or a crevasse:

one unplanned bill away from

tipping point one illness

away from seeing the

whole edifice of

their lives come

tumbling down

with no one

around to

help put

any of it

back

together

again

It’s something rather ironic but no doubt deliberate that, as with the verse of Fred Voss, Hayes’ often sparely written and unadorned poems have lyrical and declamatory Withmanesque titles. But there are often declamatory passages within the poems themselves, as in ‘Stitching This Universe Together’:

don’t we need these jobs

so that we can stand in front of mirrors

and look at ourselves

without feeling worthless

or disconnected

like a CEO must

like a President or a Prime Minister must

like the head of an HR department must

don’t we need these jobs

in the same way that Martin Luther King needed his dream

in the same way that Rosa Parks needed to stay on that bus

in the same way that the Wilding needed equality

‘The Men I Work With’ is an impassioned paean for Hayes’ fellow employees and the pastimes that keep them sane inbetween punishing shifts:

a man I work with

cries every time it gets too busy

throws his head back onto his fat neck

and stares up into the ceiling

all the while muttering under his breath

how thankful he is that he still has a job

and hasn’t been allowed to die yet

a man I work with

goes home every night to make Airfix models

only to hang them from his ceiling

or spread them out across his bedsit floor

reenacting the battle of Midway

or the siege of Leningrad

talking all day about historical wonders

what men and women have been capable of before

a man I work with

gets so drunk in the nights after his shifts have finished

that when he comes in for work the next morning

he looks as small as a little death rattle

rattling away at his keypad

with eyes that shine through his pain

and a smile on his face

that has no right to exist

the men I work with

haven’t written any great books

that everyone talks about

they haven’t painted any great pictures

or composed a symphony

that can bring a tear to the eye

but they have worked for years doing 11-hour shifts in a dead-end job

The ‘system doesn’t seem to want to help’ ‘The Telephonist Who Works More Than 36-Hours A Week’:

preferring instead

to let her tilt even more

until she finally takes on so much water

she will go under

and sink to the bottom of the harbour

along with the rest of the wrecks

There is always the health and sanity-checker of ‘Calling in Sick’:

nothing surprises me or shocks me anymore

apart from the truth

which I have found through my years of experience

to be absolutely fucking nowhere near

what comes out of a courier’s mouth

cynicism and disbelief were rife in a supervisor’s mind

at the best of times

but when it came to illnesses

and reasons for days off sick

that’s when they really could show

how much humanity

they had been able to lose.

Hayes admonishes one of the supervisors in ‘Supervisor Glynn’: ‘when you think about all of that flesh and blood/ and all of those smiles and souls/ he took apart over the years inside that control room/ just because he was allowed/ to feel that he could’. ‘The Blood and Smiles Yet To Be Delivered Into This World’ closes on a poignant meditation:

where we pick up bottles of wine after they have gone to bed

and sit at a window wondering about the industries of men

and the blood and smiles that are still yet to be delivered into this world

whether or not they will be the ones

to write that song or poem

that will change everything

Hayes often swipes at much of the middle-class complacency of the contemporary poetry scene, as in ‘Roar!’ where he notes while his supervisors are ‘screaming and shouting at us/ that we were ‘idiots’/ and ‘morons’/ poets are writing about the shadows tulips cast in distilling light’, or:

poets are writing about the smell of their dead father’s tweed jackets

and studying what type of poem they should write

if they want that editor

to put them in their magazine

…

poets are writing gutless poems

about irrelevant subjects

using fake words

…

the trouble is

it often doesn’t mean anything

because none of their lives

are ever falling apart

quite enough to make their poems

ROAR! ROAR! ROAR!

One wonders whether this Roar! is also an allusion to Shelley’s ‘Rise like lions after slumber/ In unvanquishable number’ from The Mask of Anarchy. There then follows another poem even more pointedly aimed at complacent contemporary poets, with its title taken from a line in the previous poem: ‘As The Poets Write About The Smell Of Their Dead Fathers’ Tweed Jackets’:

a crust of dry bread has become the dream of millions

running water and one bar of electric heat

amenities out of reach for a quarter of the globe

as CEOs stand in their kitchens

warming their feet on underground heated slate tiles while peeling an avocado

slate

ripped from the earth by people whose hands have to squeeze the last drop

of milk from a dead breast

wring a sleeping bag dry

so they can sleep at night without freezing their guts

people who have jobs but still have to queue in food banks just to feed their

families

as their Prime Ministers and Presidents talk about nuclear wars

destroy

…

just because their God lost an election

and had His fingertips replaced on the trigger of a gun

…

closed all of their factories

people who once worked in industries long ago shut by progress

who once used their hands to rivet together ships haul a piece of steel out of

a blast furnace replace

…

as the poets write about the smell of their dead fathers’ tweed jackets

are Forwarded £5,000 for a poem about the opening of a wardrobe

have enough time on their hands

to stand in front of mirrors

contemplating whether they exist or not

and books about wizards and bondage

sell millions

‘Fuck Off Darlings’ is a rebarbative twos-up to the poetry prize scene.

Roar! is chockfull with impassioned pleas: ‘This Job Has Us In Its Mouth and Is Shaking Us About In Its Teeth’:

on offer like a can of Coke

on offer like greasy chains

for us to slip our wrists into

…

the entire Universe up there

on our side

with the sea and the stars in our eyes

and that unbeatable laughter rising up out of our throats

to prove it

And a euphoric expression of escape at the end of ‘Friday Afternoons’:

that we can see for the first time

why the apple fell onto Newton’s lap

Mark Anthony’s face

while he was making love to Cleopatra

feel the fingers of Beethoven

moving over those keys

until it all comes so perfectly together

the moment we put our foot outside that door

and walk up that road

feeling like Beowulfs

out looking for our Grendells

In ‘How To Disappoint Almost Everybody’ Hayes evokes the crushing sense of occupational underachievement: ‘we didn’t need the supervisor’s disgust or hate to know that we weren’t making music/ we knew that sat in those big controllers’ chairs we were in the crosshairs of a sniper’. He next addresses the sense of a wife’s disappointment in him in ‘Some Nights We Get It With Both Barrels’ by imagining her thoughts: ‘‘Why did I have to get with a man/ who has no life-plan,/ who has no schemes/ or big ideas,/ who just works and works and works/ making money/ for other people?’’.

One poem says everything about employment by Phoenix Express in its Tressellian title alone: ‘In Between Stockholm Street and Syndrome Way’. In ‘The Ground in Dirt’ Hayes empathises with the daily chores of the office’s cleaners:

the cleaner pulls out polystyrene cups, discarded sweets, used tissues,

crumpled up crisp packets, pen lids, Gunster sausage roll wrappers

and bits of cucumber and tomato that have fallen

from the sandwiches the controllers eat

and then foot-soled into the carpet.

In ‘Getting Buzzed By the CEO’ we’re almost in the territory of Reginald Perrin being summoned in to his overbearing boss C.J.’s office:

and then I suddenly realised

that this office

with all its leather

and mahogany

and chrome

and cool air

was actually

a gigantic trap

In the wonderfully titled ‘Like A Sniper Wrapped Up In Wine’ Hayes conveys:

you have to sit here patiently some nights

and not worry about Donald Trump

the troubles in Syria

or the colour of a poppy

…

you have to stay patient

like a tiger in a forest

moving a leaf aside with its nose

like a spider

shooting silk out of its arse

like a bluntnose shark

who feeds on a decaying sperm whale

then won’t eat again for another year

…

you have to sit here patiently some nights

like a sniper wrapped up in wine

levelling your crosshairs at something

sometimes the words and meanings come into sight

sometimes

they don’t

Ox could be described as a kind of composite working-class reimagining of Ted Hughes’ Crow merged with George Orwell’s Animal Farm. Here Hayes has chosen to theme an entire collection within one metonymic framework, and it’s particularly effective for his purposes. The eponymous Ox is a personified synecdoche presumably deriving from the idiom ‘strong as an ox’ which alludes to the strength of the employed animal for pulling ploughs. Hence the Ox is the exploited worker, the put-upon employee. The opening poem ‘Ox’s Descent’ sets the tone: ‘when Ox got strapped into his first plough/ it was like a revelation/ only with mud and hunger and fear’. In ‘Ox and The Bottom Line Is All That Counts Method’ we get a consummate metaphor for employment:

so he begins working out how many days off each ox has

due to coughing

or lungworm

or cryptosporidium

cross-referencing the results

against which oxen eat more hay

or which oxen demand more of his attention

to look after

trying to separate one ox from another ox

to see if he can justify

its slaughter

‘Ox and the Struggle Against the Single File Entry Method’ demonstrates the punitive nature of employment, especially the type which circumnavigates basic rights to sick pay:

there is nothing wrong with you

you are faking it

you are full of shit

and you will not eat tonight

then he twisted a black mark into Ox’s forehead

with his thumb

and Farmer stayed true to his word

withholding Ox’s food

so that Ox remained hungry

letting out moos

deep and low

and this goes on

not only for oxen

but for nurses and fireman and fruit pickers

‘Ox and the Great Big Identity Trick’ echoes both Tressellian and Orwellian satires in its comment on de-unionised labour and thwarted collectivism:

every animal on the farm

wants what they want

as Farmer sits in the safety of his farmhouse

laughing away at his luck

as not only does God obviously love him

but it seems that all the animals

have fallen for The Great Big Identity Trick

become so wrapped up in themselves

that they’ll never get together now

to burn his farmhouse down

‘Ox and Those Voices’ is a psychological play on repressed anti-capitalist sentiment and resentment:

so for the rest of his existence

Ox ate his food

and pulled his plough around

to a looped soundtrack screaming out inside his head…

KILL THE FARMER!

KILL THE FARMER!

‘Ox Begins To Give Up’ appears to depict working-class complacency in terms of the perception that things can’t be changed:

wedged up against a bale of hay

smoking a cheap cigar

laughing

no one can threaten me anymore

I am slave of oxen

I am prisoner of the field

I am victim of all I survey

The cigar being a perennial motif for capitalists (so much so that cigar-smoking Labour prime minister Harold Wilson smoked a pipe in public), it seems Ox is falling into the trap of starting to think he has some kind of control over his circumstances. But no so, as the rest of the poem reveals:

Ox took a deep drag on his cigar

puffed a cloud of smoke into the air

and said

listen mate, we are oxen

always have always will be

oxen make things happen

for Farmer only

so there’s no need to worry

no need to get anxious

you just gotta give in

we work and eat when we’re allowed

and then we don’t

so relax brother

put your dreams away

and make the most of it

there’s nothin’ you can do about nothin’

‘Ox Confronting Technology’ reflects the constant threat of further mechanisation and redundancy: ‘when the tractors were unveiled/ the oxen knew that their time was up’…

no one knows these fields like we do

we have trodden and heaved your ploughs

over every square-inch of these field

for years

we are the best and most equipped

for the job

Farmer had to agree

they had indeed trodden and heaved his ploughs

over every square-inch of his field

and no one knew them like they did

all that was left to do

was to see if they could drive the tractors

obviously this didn’t go so well

even though they knew which way to steer them

they had trouble getting themselves up on the seats

and their hooves couldn’t grip the steering wheels

and when the tractor’s engines roared into life

they thought the end of the world was coming

…

needless to say

they didn’t get the job

and now they lay in their leaky barns

nursing headaches

ashamed

and redundant

For me, one of the most effective figurative poems is ‘Ox In Hunger Wonders About His Colleague Mole’:

the starter

a torn-out tongue

tender with years of grubby language

softening up its muscle

next

the Earth’s platter

spread with the scorched heads of its occupants, mouths agape

stuck in charred-black laughter

from the high temperatures of a sudden cooking

loosened teeth

to be sucked clean of their leftover gum-flesh

hanging on to their upturned roots

as an ache inherits the mouth of all those that are left

the wine

blood upon blood

deep as the dark of Moles’ eyes

after culling

then later

dessert

the cream of the white fat opened at Orgreave, beautifully rendered

beaten soft and silky to drip

like victory down their iron throats

‘Ox In Forced Retirement’ again tackles work as a punishing affliction: ‘Farmer is an evil monster/ who hides behind his/ thwacking stick’.

Inescapably the exploited employee ends up propping up their psyche through addictions, whether over the counter sedative medications or drink, as in ‘OX ON ALCOHOL’:

we don’t need that bloody Farmer

to feed us

keep this leaky barn over our heads

who does he think he is

putting these paltry amounts of food

in front of us?

are we supposed to be thankful

for his meagre wage packets!?

he’s the one who should be thankful!

…

and because this seemed

like the greatest idea ever at the time

it wasn’t long before all the oxen

were gathered at Farmer’s door

under a moon that illuminated the whole courtyard

bone white

Afterwards comes ‘Ox With A Hangover After the Crime’ with a chilling repercussion: ‘take that/ you ungrateful ox/ it’s the abattoir for you boy!’ Another of the most effective figurative poems is ‘Ox at the Gates of Heaven’ because of its focus on imagery:

and then there was the single file entry method

funnelling the herd in

to reduce the levels of stress

the white rubber wellington boots

flecked with blood

protecting the feet of a Vasily Blokhin

the silver hooks of a Torquemada

to upturn the world on its head

the white ceramic guttering of a Pol Pot’s throat

accelerating the rivers of blood

into the stomach of the Earth

the burnt out Fiat smoking in the abandoned skull

of a Mussolini

the black bud of poison squeezed from the festering anus

of a Thatcher

…

the empty testes

of a Trump

the lullabies

of a Marine Le Pen

then God’s final judgment

a bolt through the head for all

and a barcode slapped on your flan

to get you out of the gates of this Hell

In ‘Ox and Cow Under Moonlight’ Hayes employs a dialogic form. ‘A Night in the Leaky Barn’ includes the wistful trope: ‘until morning/ when the strapping into their ploughs/ diverted their hunger away/ from each other’. ‘Ox Witnesses Yet Another Birthing’ is one of the shortest poems in Ox, but packs in much profundity in its lyrical scoop:

hot blood has already knitted the words of its poem

warming up not only its mother but other planets also

there is a depth to this deeper than known soil

it sits somewhere in darkness wearing darkness

we are resigned unknowing how it all works

no blueprints survive

we must go blind into its waters every time

As does ‘Ox Gets a Visit from Social Services’ in its closing two lines: ‘they were prisoners of their own song/ Hunger it was called’. There’s a wistful aphorism in ‘Little Ox’: ‘I used to believe in something/ once’. ‘Ox Tries to Sleep’ deals with the despairing employee’s suicidal ideation and has echoes of a similar episode for Tressell’s Frank Owen in The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists:

and this sensation

that there was a cliff-edge near by

that would solve all of his problems

…

there was no choice though

Ox had to face the black

if he was going to sleep

so Ox took in a deep breath

and closed his eyes again

the black descended almost immediately

the fear and panic rose

but he held on grinding his teeth

until he found that cliff-edge –

or it found him?

it’s hard to say exactly how it happens –

and fell off its edge

and as Ox was falling

he suddenly realised that this blackness

the fears inside him

that was him

that was what

he was made of

The equally despairing ‘Ox Dealing with The Light’ ends on a sublime note:

which all helps go to prove

when you see an ox

momentarily pause in a field

swishing his head from side to side

like in a great struggle to set something free

there’s no need to worry

about the revolution starting anytime soon

because all it is

is Ox pretending again

that he’s got something going on up there

when really there is only blackness and fog

and the pain from all of this light

‘Ox and the Song of the Strong’ closes this powerful collection on an almost defiant note:

he knew he had strength though

that he could pull all of the stars back into place

push all of the oak trees back into the sky

lift all of the oxen up off their knees

he knew

that his blood was thick with stamina

that it was made up of all the blood that had ever been before

and would ever come again

and this is what enabled Ox to sing

because after everything had been and gone

it was only blood and strength

and the songs

that would remain of him

Moving into Underneath, ‘Why Not a Job’ is a dialectical materialist plea but which oddly—perhaps ironically?—suggests that our gods should be our jobs:

why not a job

to dedicate your life to

why does it always have to be

a man who died on a cross

or who sat under a fig tree

or who was the last messenger

to bring the words of an invisible and unreachable God to us

rather than these Gods

they keep rattling their cages for

why can’t these jobs be our Gods

our way of earning a living

the religion

we would die for

rather than the colours on a flag

That last line has particular poignancy at this disturbing time of Far Right ‘flag graffiti’. ‘5 Am Early-Shift Tube Ride In’ is another impassioned plea on behalf of fellow exploited workers:

who are these men

speechless now as worms

bright as flamingo

emptied out into luminous orange suits

SKANSKA – KIER GROUP – GALLIFORD –

BALFOUR BEATTY – MACE –

marked plumage of high-vis vests

marching out onto the salt-flat

‘The Night Worker’ is a visceral piece which skirts the subject of self-harm:

slowly the ghosts rise out of his mind dripping wet with mischief

crawling down the inside of his back

duelling in amongst the turrets of his vertebrae

swinging on the nerve-ends of his sciatica

playing out their deep and lonely dramas

that he has become the battlefield and protagonist of

tick tock

slowly the clock goes

carving each second of his shift into his own forearm

until the first cutting-torch-flame of the sun cuts a crack in the black

‘Kneeling’, as its pithy title suggests, is about the supplication of the exploited employee. ‘Lucky Charms’ is a touching poem that provides an office survey of the various mini-mascots collected around each employee’s computer space, the kind of shrine-like superstitious self-comforting that one sometimes sees in taxis with crosses, crucifixes or rosaries dangling from the rear view mirror. There’s one particular poignant detail Hayes notes of one of his colleague’s: ‘and Lucas/ hangs a picture of a man starving in a potato field on his headphones’ hook/ as his’—this could possibly be a reproduction of one of van Gogh’s earlier pictures from his ‘peasant characters’ period.

In ‘All of This Blood Going On and On’ we find Hayes in more figurative mode and with an unexpected swerve towards a spiritual faith:

I used to think that God doesn’t exist

that it was a thing made of stone

set in old mouths

that grew in graveyards

over plumb trees

and dreams

I used to think that all of the people who believed in it

were ignorant

gargoyles

who wanted to fill their hearts

with even more dust

because they were too frightened

by what running blood does

To Hayes, God exists in small acts of creativity: ‘in Chantelle’s hands who makes origami dragons and cats in between/ the calls she takes’. But God also exists in those who rely on chemical means for their small euphoria :

in Marcus the van controller

who comes in every day pumped up like a gladiator on coke

ready to make everything happen

with the magic of his tongue the agility of his mind

and the speed of his fingertips it lives

even in Merve

sat hungover in his chair

(Note the very effective g-alliteration in that passage: ‘gladiator’, ‘magic’, ‘tongue’, agility’ ‘fingertips’, ‘hungover’). ‘Foxconn Suicide Watch’ depicts a fellow worker who is so overworked that she is covertly monitored by the poet and colleagues for her own safety:

as Judith crosses her legs

and holds on to her wees

not wanting to get a black mark

pressed into her forehead

…

not wanting

to not be able to put a bowl of pasta in front of her child’s mouth

or be able to buy a plant

that she can water and watch grow up into the sky

as the system blocks out the sun

drains her blood away

from the heart she’s learnt

has to be made to stay awake has to sometimes

be made to keep

on beating

even when all the rest of her is so tired

so fed up

that all it wants to do is stand up on a roof

and fall

face first

into eternal sleep

In ‘Feeling Like A Man Again’ one of Hayes’ colleagues is sacked for hitting supervisor ‘Glyn’ over the head with his computer keyboard: ‘as Maurice sat there for a moment letting it all sink in/ knowing that he’d finally felt that great big bird arrive…

squawking up into the sky

so that it came out of Maurice with him picking up that keyboard

and smashing it over supervisor Glyn’s head

slowly getting up afterwards

picking up his glasses case vape and asthma pump

before silently walking out of that control room

Although he has now lost his job, the experience feels perversely emancipating for ‘Maurice’ who finally escapes Phoenix Express ‘unemployed/ out into the sun’. In ‘Singing Like An Angel Again’ Hayes depicts another more contented colleague:

as Magic Mike disappeared back into the workshop

with his fingers and his heart

to sit on his dirty old chair

listening to rap on his headphones

not knowing or having a clue

about half as much

as he was keeping this world together

The ironically titled ‘The Souls Of Men’ shows how masochistic the capitalist work ethic is on the part of employees some of whom seem to lap up their exploitation:

it’s amazing the amount of men who keep coming

through the doors of this control room

wanting to drive these vans of ours

it is like there must be some kind of cauldron somewhere

where the souls of these men

are gently stirred until they are formed enough

to grab onto the tails of smoke rising up into the air

…

it’s how they hang on

to that feeling

that they mean something

that despite everything

they are at least going to try to find a way

that enables them to walk through the fire

with their heads up

before their souls finally give up trying

and head back to that reservoir

In ‘We Need Payslips’, the simple pieces of paper transubstantiate into other pieces of paper with which workers can pay bills and rent to keep themselves surviving whilst they have to rely on credit to actually be able to afford much of the product they contribute to producing—a perpetual cycle of exchanging token for token, symbol for symbol, in the ritualistic mock-mystical travesty that is capitalism:

we work to make it turn into food

to make it turn into heat and electricity that keeps our families warm and

happy we work

for the council tax the rent the laughter and song

we work like Standing Bear worked we all work

for the hill in the mists at the back of our minds that we were brought up on

the land where we once ran free

The juxtaposition of exploited workers with the oppression of the Native American Indians is an interesting one. The title poem of Underneath draws its despairing conclusions: ‘God will not save us we are from Underneath/ His hands have been turned to shape a different valley/ silicon greenbacks and the wise selling us short before dumping us’. And this is a perennial state: ‘Underneath it has always been the same’.

The wonderfully titled ‘Cloud Workers’ focuses on the distinctly non-ergonomic aspects to utilitarian technology in terms of living spaces: ‘they have put two black boxes on the wall next to the intercom door of our flat’. Hayes drily comments: ‘the difference between death or a continuation of the pain/ Hansel and Gretel wouldn’t have needed all of those white pebbles/ if they’d had Google Maps’.

‘Brighton’ is a nostalgic poem in which Hayes takes a day trip to Brighton—the common respite destination of sea air taken by many a Londoner—where he reminisces on formative visits with his mother when he was child:

I remember my mum used to take me to sit on

near the old burnt down pier

when everything was younger

and pubs used to shut in the afternoon

…

the huts that used to house gypsies with boney hands

that used to spread out over crystal balls

telling you your future

But strangely the poet prefers the rusty decay of the almost vanished West Pier of the present, perhaps because in its neglect it is somehow more real:

but I like it better now

this charcoal black tongue sticking out into the sea

the twisted metals of the dance hall frame

pieces of iron fractured like an old woman’s teeth

the legs still sturdy

charred roots pinching their toes into the seabed

just about managing

to always keep it propped up

memories live under the sea she said

they twist and turn

stretching themselves out around our submerged architectures

like nightie-wearing ghosts

and sometimes the tide breaks them free

so that they rise for attention

The poem closes with a haunting image of the ‘ghosts of the girls and boys’ of more prosperous Brighton times still ‘out there/ at the end of our burnt down piers’, but this is positive in the sense that it places emphasis on the infinite revitalisations of memory and imagination. ‘Nothing Left To Dream About Anymore’ depicts the parlous prospects of the younger generations of today saddled with enormous university debts and then often offered either poorly paid employment or exploitative unpaid internships:

Edward made the decision

to give up his pursuit of a job in economics

that he’d spent 3-years getting a degree for

to come and work in our control room

as a right-hand man

because he couldn’t afford

to work for another 6-months with no pay

just to get a stamp and a tick on his CV

But Hayes notes that bosses’ prospects are entirely different:

but there is one man

in this building

who has realised his dream

who has a Bentley parked in the yard outside

to prove it

who sits in the boardroom upstairs

‘Where Are The Working Class Now’ seems to be an impassioned plea emphasizing how capitalism divides and rules and ultimately promotes racism and fascism by making white British workers resent cheap foreign workers (particularly those of colour) with the myth of them “coming here and taking our jobs”; it then imagines if all British workers were white rather than a multi-ethnic mix, which is where it seems to get a little muddled in message:

imagine if all of the workers in this city were white

imagine that

imagine

the Uber driving Somalian cabbie

white

the Filipino nanny

white

the Colombian cleaner

white

the Brazilian courier

white

imagine

that

imagine

the Nigerian traffic warden

white

the Afghan phone repair stall owner

white

the Indian corner shop owner

white

I am assuming the essential message here is how a collective working-class consciousness is forever muddied and forestalled by superficial dividing lines, mostly visible ones, cynically extrapolated for repressive and divisive purposes by right-wing newspapers and mainstream politicians, in short, the props of the exploitative capitalist class. The more effective and important part of this poem’s message however comes at its close:

imagine

if the colour of our blood

and the stench of our sweat

was more important

than the colour of our skin

who would

then

be able to split us

apart

see?

why

they did that?

Underneath ends on possibly its’ single most effective poem, ‘Friday Nights at the Typer’, again, because of its use of more figurative language to get its message across:

and inside

the rising and sinking of lungs

the stomach

a sea of beer and rose wine

the half-eaten corpse of an idea

bobbing about in the tide of a gin-coloured moon

a jubilation to a god

whose name now cannot be remembered

who stands back from the edge of the lips

under the dark sanctity of a tongue

bloated by the job

the mind

a lunatic thing

tiring of the ongoing experiments

made up now of the skin-cells of a clown

scooped from under the fingernails of its laughter

jokes

the camouflage of a shoulder-blade

continually wedged up against the sun

and over here

sat in the ear

the removed mouth of a mouse

squeaking away about the scarcity of cheese

the threat of the trap

the map in the claws of a fat cat

until finally

sleep suddenly comes

like the clunk of an irreparable fault in an engine

like the dark centre of a panther

This poem is a triumph of imagery and alliterative effect.

Finally, Hayes’ most recent collection, and the last ever to be published by Smokestack Books, Machine Poems. The short poem ‘The Worker Writer’ serves very much as an epithet for the poet:

what does he know

apart from the shrill bell of his alarm clock and the tube map

that gets him in to do their dirty work

there are no fields for him to saunter

or drag his limbs through their poetic mud

or regurgitate with crafted pen or plough

heaven’s true story

his is more a theft from the earth than a sharing –

when you’ve been used for so long

it’s not such a leap to become a user –

and no joy does he get from it either

other than paying the rent and showing

everyone

what he and his ilk are capable of

‘The Sophie Principle’ is a poignant depiction of an overworked colleague during the Covid pandemic:

Sophie knew what was what

she worked on our Track & Trace desk

monitoring the Major client’s jobs

letting them know when something was delayed

or was about to go seriously wrong

but whenever it got too busy

without anyone noticing her looking around for some help or support

her anxiety would kick in

and she had two big bottomless eyes

like something deep that knew the sea

and you could sense that she was softer than an octopus

only twice as wise

that she’d learned to grow three hearts

one for working one for living and one for her anxiety

while the others in there were shark-cold with their metals and steel

while she was all warm and flesh and caring

with the children still to come

It closes on the beautifully lyrical aphorism: ‘how much more beautiful and rich we are than the stars’. ‘Deshane Jackson’ is a similar poem-portrait which uses petrol as a metaphor for the fuel that powers exploited employees: ‘a bit of unleaded/ pumped into the insides of the machine/ can sometimes lessen the effects of rust/ felt in the throat and stomach of a veteran’.

Machine Poems is another titular synecdoche, the ‘Machine’ meaning the worker or employee, and here is a definite intermingling of the legacy of Fred Voss’s machine-operating factory poetry, particularly his collection Robots Have No Bones (Culture Matters, 2019). ‘The Unsaid’ produces the apothegm ‘10 words in 11 years/ which was more than enough/ for both of us to know/ almost everything’, which very much sums up how 90% of true human communication happens outside the limited parameters of speech. ‘The Flaw’ is nicely figurative:

you found the way in between the beauty of acorn to oak

…

but for the instinct I planted in your gene

that you cut free

dashed into the boiling sea

and replaced with your machines’ language

The wonderfully titled ‘Widening The Divide’ trips into a familiar Hayesian allegory:

the Inventor asked

who is it you worship?

the creatures replied

love money and rage

…

the Inventor knew then

that he hadn’t quite cracked it

that something else was needed

to help widen that divide

While ‘Watch Me Destroy All of That’ is a short monologue by this ‘Inventor’, who may be the God of Work, the Molloch of capitalism: ‘let them suffer/ let them come to me/ with their rent problems and their electricity bills and their damp/ on the bedroom walls of their children’. ‘The Inventor Creates A Device’ first seemed to me a kind of dialectical materialist take on the exploitative and repressive aspects of organised religion in capitalist societies; however, Hayes has since elucidated that the poem is about the invention of the internet and ubiquitous mobile phone as portals to a (to paraphrase him) ‘mind-colonising’ plethora of social media apps (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter etc.) and 24/7 news and associated ‘doomscrolling’, all of which Hayes figuratively characterises as a kind of new religion:

the Inventor thought

this is coming along nicely

they are putting bears in cages

writing songs about suicide

they have become ugly and ripe

all they need is a little bit more help

and I will be ‘this close’

to colonising them all

…

because even though it wasn’t real

like the old church

they came to his new church online

donating more money per month than they’d ever done

and their children suddenly fell quiet

turned in on themselves

peering into their filthy nests

rather than out

Again, this poem is more effective for its use of figurative language, its emphases on imagery: ‘like when Joan of Arc got burnt/ truth and lies became almost indistinguishable/ both a spear laced with venom thrown into a billion hearts at once’. ‘Isolation’ includes the aphorism ‘all pushing the same precarious anxiousness of existence’. ‘The Screams of the Supervisors’ is imaginative in its attempts to evoke the sounds of explosive supervisors with those of the animal kingdom:

then other times they are like the beatings of a silverback’s chest

…

sometimes they are like the bite of a hyena into the back of your neck

other times they are like the annoying whimpering of a chained-up dog

…

but mostly

they are like the coughing-up bark from some hideous animal

afflicted by a great disease

coming from somewhere far of

in the dense electronic wood

The ironically titled ‘Learning’ depicts the exhausted worker waking up for another day at the treadmill, described like an electrically prodded cow, or, indeed, ox: ‘feeling like a carcass electrocuted alive by the alarm clock’. But this titular ‘learning’ refers in part to a shadow-knowledge at how to get back at the capitalist system, and how to mentally escape from it:

to learn

to learn how to steal from those who need to be stolen from

Tesco’s Sainsbury’s TfL

Waitrose John Lewis British Gas

and for when it gets too unbearable

to learn how to sit in the dark drinking dark

Hayes makes a more than apposite juxtaposition:

where all of the supervisors think they are in charge of Rome

who will inspect your performance stats

like they used to inspect the teeth of slaves on a platform in the Campo de’ Fiori

to see if they were healthy enough to keep.

It comes full circle back to the livestock metaphor: ‘to learn how to use yourself/ you are a piece of meat/ you are a cow a sheep a bull a hooved thing’. The David Mercer-esque titled ‘What Resistance Remains’ is another aphorismic piece with pools of industrial lyricism: ‘you will sleep under the iron moon’. ‘Hope’ is an impassioned paean:

it wasn’t how much they were being underrepresented

…

it wasn’t the happiness of fools

it wasn’t the romanticism of poets

it wasn’t even the knowledge

that they were made up of blood and bone

…

no one could work out exactly what it was

but while it lasted

the machines could war over their elections and territories

as much as they wanted

The curse of employment in capitalist society is a Sisyphan one:

because all the creatures needed

was a little bit more of it

in a song in a poem in a kiss

and that would be enough

to keep them going until the next month

Machine Poems ends on ‘The Definition of What’s Not A Machine’, which answers its title in an apothegmic final three lines: ‘when there is an urge an urgency/ in the things that you do/ because you know that one day you will die’. Amid the casual language there are increasingly more figurative seams apparent as we travel forwards chronologically through Hayes’ collections: ‘his fingers began to dance over his keypad like dragonflies’ (‘More Magical and Beautiful Than Any Machine’); ‘spinning around while dragging deep down on their cigarettes/ before throwing back their heads/ and laughing that smoke out of their mouths’ (‘Our Serengetis’).

There are the more typically gritty observations: ‘spinning around while dragging deep down on their cigarettes/ before throwing back their heads/ and laughing that smoke out of their mouths’. And in ‘Work’ comes a crowning epitaph: ‘there is no respite from it// it is the only thing that pays the rent/ the food the electricity the toothpaste/ the plasters Bonjela codeine and wine’—opiums of employment. In these aphorismic flourishes there’s something of late Hackney Writers’ Workshop poets David Kessel (1947-2022) and Howard Mingham (1952-1984).

Hayes’ poetry fits the proletarian tradition in that it is almost entirely shaped by and concerned with the poet’s paid occupation; and, paradoxically, it is this despised daytime occupation that provides succour for his more authentic spare time occupation as poet, since it gives him his subject. In that sense Hayes is the direct baton-receiver of the recently departed Fred Voss, not only in methodology but also style: the often unpunctuated, rangy lines (and titles, try ‘riding home from work with the precariat on a packed Bakerloo line again’), and the use of ‘machine’ as both a leitmotif and a metonym for worker/employee.

There are some other contemporary poets who write about employment, one being Paul Tanner (Poems for Shop Workers, The Penniless Press), but they are exceptions. The candid content of Hayes’ work, particularly in Roar!, prompted his employer to threaten him with the sack, which is largely why Hayes began to use more symbolic imagery from the metonymic Ox onwards. Who says capitalism can’t sometimes feel threatened by poetry?

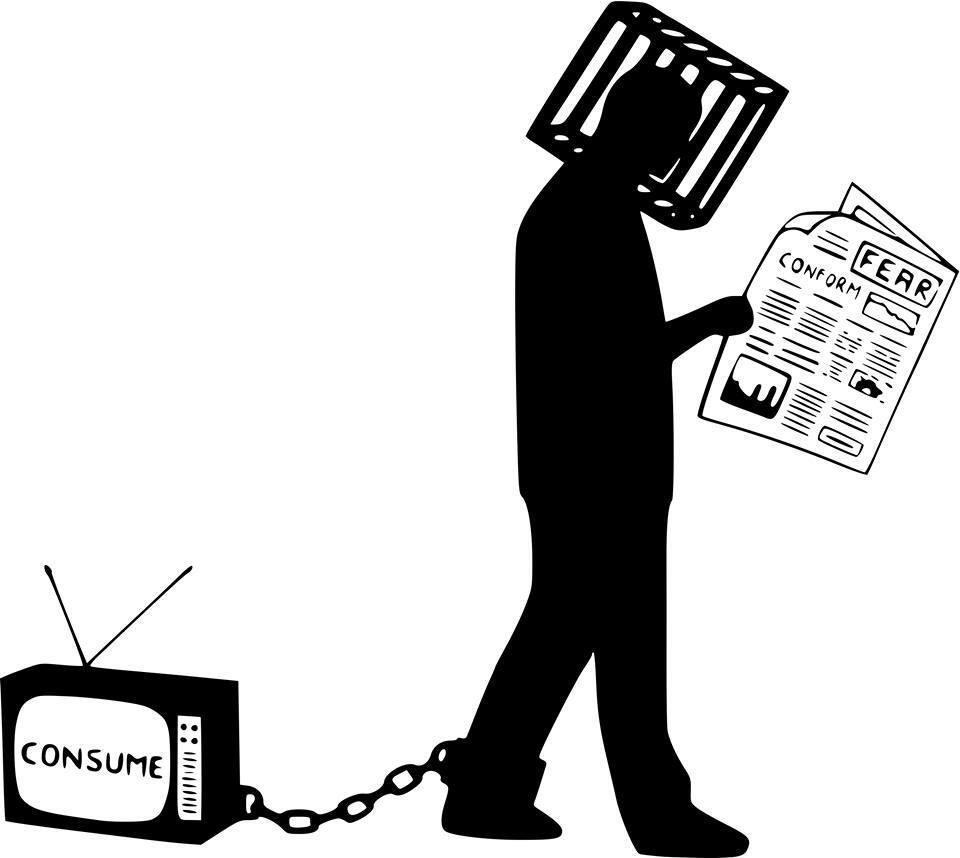

The poetry of Martin Hayes is more than the sum of its parts; it is one long, circuitous but ever-moving verse-testament to the defiance of the human spirit and imagination in the face of the remorseless exploitation of employment under capitalism. That so much impassioned and effusive self-expression can pour out from the pen of an underpaid and overworked employee for an exploitative private company resoundingly demonstrates how capitalism ultimately fails in its attempts to turn us into worker-consumers incapable of spontaneous creativity in what spare time we are permitted.

Some parts of this review were incorporated in an edited version/sampler published in the Morning Star on 9 September 2025 under the title ‘Poetry of work’