Our Culture is a new series from Culture Matters exploring the relationship between culture, class and capitalism through a Marxist lens. The series investigates how capitalism extracts value and integrity from all kinds of cultural activities and experiences, turning creativity into commodity, yet still leaving space for subversive and emancipatory potential.

Our Culture also seeks to imagine what cultural democracy might look like – how socialist principles of common ownership and management could be applied to all forms of culture by a future left government, through realistic policies and ideas for change.

If you’d like to contribute an article, poem, artwork or song to the Our Culture series, contact us at info@culturematters.org.uk.

CULTURE AND CLASS

by Jenny Farrell

“The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas, i.e. the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force.” – Karl Marx, The German Ideology

In this interview, Jenny Farrell discusses the meaning of culture as a field of class struggle, between the “first culture” of the ruling class and the “second culture” of the working class. Drawing on Marx, Lenin, and Gramsci, she argues that culture is never neutral – it either reinforces domination or becomes a tool of resistance. Alan McGuire then follows up with questions that deepen the conversation and set the pace for the series to come.

In any class society, culture is not a monolithic entity, but a field of struggle defined by a fundamental dialectic: the conflict between a “first culture” and a “second culture.”

The “first culture” is the culture of the ruling class. It is formulated “from above” and plays a dominant role, seeking to determine the entire cultural formation of society. It represents the ideas, values, and lifestyle of the exploiters, often functioning as an ideology that obscures class antagonisms.

In opposition arises the “second culture.” This is the cultural expression of the exploited and oppressed masses, formulated “from below.” It is not merely a subset of the national culture but a qualitatively different phenomenon. In a precise sense, it constitutes a form of human self-assertion and self-formation under conditions of oppression. It is a “culture of resistance,” through which the working class affirms its humanity, articulates its ideals and hopes, and develops its inherent potential. This process is core to a materialist understanding of culture: humanity’s active self-production by transforming both external nature and its own nature.

The second culture inevitably develops distinct ideological qualities born from the collective experience of suffering and resistance. These can be summarised as subversive, radical, anarchist, democratic, and socialist. Its most fundamental form is the labour movement itself, which evolves from rudimentary rebellion into organised economic and political struggle.

This framework is dialectical. The two cultures are not separate; they are actively connected and define themselves in opposition to one another. They are an essential component of the class struggle. As Lenin established, within every national culture, there are “two national cultures”: the dominant bourgeois culture and the emergent elements of a democratic and socialist culture created by the “toiling and exploited masses.”

Crucially, the second culture possesses a transnational, internationalist character. Because the life conditions of workers are fundamentally similar across nations with identical economic structures (capitalism), their cultural expressions of resistance share universal features. It constitutes the basis for an “international culture of democracy and the world working-class movement,” surpassing regional and national limitations. This point was vividly illustrated by James Connolly in Labour in Irish History, who traced a continuous thread of democratic and socialist ideology within Ireland’s anti-colonial and class struggles, declaring that “the same wretched cabins have been the holy shrines in which the traditions and the hopes of Ireland have been treasured and transmitted.”

Therefore, the task is not for the working class to emulate bourgeois culture. Instead, it must consciously develop its own cultural expressions — from art and literature to its forms of organisation — to understand the world and change it. To promote this authentic working-class culture is a radical act: it challenges the hegemony of the first culture and nurtures the consciousness through which a new world is built.

Alan McGuire: You describe culture as a struggle between the first culture and the second culture of ordinary people. How does that show up today?

Jenny Farrell: The dominant culture doesn’t just ignore working-class experience; it actively marginalises, misrepresents, and demands its alteration to fit hegemonic (middle-class) narratives and commercial logics. This isn’t about access to high culture; it’s about the power to define what counts as a legitimate, interesting, or marketable story.

When working-class life is depicted, it is often forced into one of two narrow, marketable genres. Either it becomes a voyeuristic spectacle of despair meant to make the comfortable audience feel pity or relief, or it’s reduced to an individual “trauma plot,” where problems are presented as personal psychological failings rather than systemic outcomes of class society. The structural critique is neutralised.

The establishment insistence that a university degree automatically makes someone “middle-class” is a key ideological tool. It severs the connection between education and class origin, effectively telling writers: “Your working-class experience is invalid because you became ‘educated.’ Your authentic voice is now this other, assimilated one.” This denies the existence of a working-class intelligentsia or organic intellectuals (as Gramsci called them) who can articulate their own class’s experience. It’s a way of silencing class consciousness by redefining the person.

Work as a site of drama and humanity is erased. The dominant, establishment culture, is often detached from manual or precarious labour, fundamentally pronounces the world of work – where most people spend their waking lives – to be boring. But from a Marxist perspective, work is a primary field of human expression, struggle, community, and – in class society – alienation. By erasing work, the culture industry erases a fundamental part of working-class humanity and replaces it with narratives centred on leisure, consumption, and personal relationships divorced from economic reality. A recent Hollywood example of this is The Banshees of Inisherin.

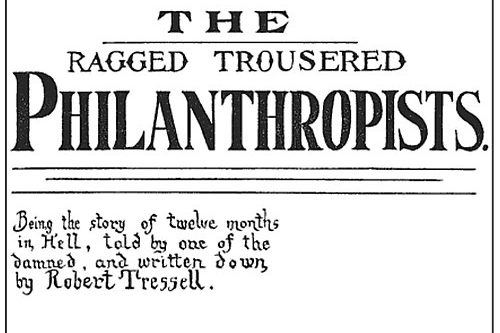

An outstanding example of the working-class expression of how work can express humanity, is Owen’s Moorish painting in The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropists. Interestingly, nobody I have met with, who has read this book has found this it boring – in fact, the opposite is true: they remember their own experiences of work and employers.

The cultural struggle shows up today as a system of gatekeeping (publishers, radio producers), narrative coercion (demanding changes to fit hegemonic tastes), categorical exclusion (deeming worklife boring), and ideological redefinition (you’re not really working-class). The goal of the dominant culture is not to engage with the “second culture” on its own terms, but to either ignore it, assimilate its artists by stripping them of their class identity, or commodify its stories into safe, apolitical products.

When working-class writers depict the realities of their lives, they are quite often silenced by these mainstream cultural powers. I have experienced this when trying to promote these three anthologies: The Children of the Nation, From the Plough to the Stars, and Land of the Ever Young. Two literary festivals, Cúirt in Galway, and the Dublin Book Festival, refused to include readings from the anthologies. Cúirt did not answer, despite repeated emails, and the Dublin Book Festival, after months of very intermittent communication, finally wrote to say they didn’t have the space. The Morning Star was, as ever, the exception that proves the rule, see here.

An example of a prizewinning working-class writer who has experienced such class prejudice, is Alan O’Brien. He submitted his radio play Snow Falls and So Do We (O’Brien, 2016) to RTE, based on the true event of Rachel Peavoy freezing to death in a Ballymun flat in January 2010. O’Brien won the P.J. O’Connor Award for Best New Radio Drama but encountered significant opposition from RTE when they were to broadcast his play. O’Brien was told his lines were crude and that the portrayal of the Gardaí was unacceptable. A significant and inappropriate change in the narrative was suggested whereby the main character, Joanne, rather than disliking the Garda known as “miniature hero”, actually fancies him, and wants him to take her out of this hellhole.

This smacked more of make-believe Hollywood that the reality of Ballymun. O’Brien’s statement that the people of Ballymun have a very different experience of the Irish Constabulary was sneered at. He rejected the changes to his script, explaining his reasons. But RTE made them anyway and many more, without further consultation. Most significantly, they changed the ending of a working-class woman dying as a result of social deprivation, metaphorically (and actually) freezing to death. Working-class tragedies are not allowed. The establishment will only accept its own interpretation, and rewrite history accordingly.

My own experience teaching Irish literature underscores what I have outlined here. My largely working-class students engaged well with the poetry of Rita Ann Higgins, because for the first time they felt poetry could be about their own life experience. I elaborate on this in all the introductions to the three anthologies of working people’s writing in contemporary Ireland referenced above: The Children of the Nation, From the Plough to the Stars, and Land of the Ever Young.

However, I don’t want to leave it at that, as this is only half the story. A crucial dimension of the cultural struggle involves recognising that throughout history, there have been artists of profound humanity operating within – or in tension with – the establishment and who created works that perceptively critique exploitation and class oppression. These artists were not necessarily representatives of the establishment at their time.

William Shakespeare is a prime example; his plays, though now enshrined as pillars of the cultural canon, contain powerful insights into the plight of working people, from the wisdom of the gravediggers in Hamlet to the cynical social commentary of the porter in Macbeth, or even the insights King Lear arrives at as he is driven out of the existing social system. While losing his mind as far as the system is concerned, he in fact finds true insight into inhumanity.

However, the cultural establishment systematically neutralises this radical potential by framing such scenes as mere comedy, emphasising formalist aesthetics, and de-historicising the works to sever their connection to social conflict. It is therefore the task of the working class, as the true heirs of this humanist legacy, to reclaim these works. By expropriating them from their sanitised, bourgeois interpretation, we reveal their critical core and integrate them into the broader project of the “second culture.”

This reclaimed art, born from a sensitivity to human misery, does not stand apart from the culture created by working people themselves; instead, it forms a vital part of a continuous tradition of resistance, connecting the historical struggle for dignity to the present-day fight for liberation. This is the dialectic of the question. But remember the artists now considered part of the establishment canon were not necessarily themselves part of the establishment when they lived. But even where they were – take Jonathan Swift for example – if they saw society and their times from the people’s perspective, their culture must be seen in tension and overlap with the “second culture” of the disempowered. And this is not normally part of the curriculum at schools or universities, or play a part in exam questions, for example.

AMcG: What could a Left government do to support grassroots culture, the ‘second culture’, in practice?

JF: To answer this, let’s look at how the socialist countries, in particular the German Democratic Republic , encouraged cultural engagement, participation and production among the entire population, especially the working class. The approach was multi-faceted, operating on several levels simultaneously including amateur participation, professional development, and mass engagement.

1. Supporting the amateur movement

- Workplace-Based Circles: Factories, farms, and large enterprises hosted regular, free workshops led by professional artists, writers, musicians, and actors.

- Community-Based Circles: Beyond the workplace, cultural centres and trade union clubs in every district offered a vast array of circles for everything from folk dancing and choir singing to photography, pottery, and creative writing.

- Showcasing Talent: The amateur movement was celebrated through competitions, festivals, and exhibitions, from local factory festivals to national events, showcasing the best amateur talent from across the country.

2. Building the infrastructure for mass engagement

The state built an infrastructure to make “high culture” accessible for all:

- State-subsidised access: Tickets for theatres, operas, concerts, and museums were very inexpensive, often work collectives subscribed to season tickets for group outings. This was a deliberate policy to break down the economic barriers to “high culture”. Every effort was made through education (schools), talks and introductions to facilitate understanding and appreciation.

- Workplace libraries: Almost every significant workplace had its own library, ensuring easy access to literature, both classical and contemporary socialist – these libraries often organised readings and talks.

3. Discovering and nurturing artistic talent in the working class

A key goal was to create a new intelligentsia of working-class origin:

- Talent Scouting: The amateur circles and festivals acted as a nationwide scouting network. Talented individuals were identified and encouraged to pursue professional training with state support.

- Worker artists: Professional artists were often formally assigned to work within a factory or agricultural brigade for a time. Their role was twofold: to inspire the workers with their art, and to encourage the artists to engage with the subject of industrial production.

4. Education and Youth Programs

The process started from childhood:

- Young pioneer centres: These were state-run centres for extracurricular activities. Children could pursue everything from ballet and painting to robotics and astronomy for free, ensuring early talent development regardless of parental inclination or income (there was no significant difference in incomes anyway).

- Music Schools: A widespread network of specialised music schools provided affordable, high-quality training from a young age.

The ambition was to create a society where cultural production was an integral part of life for every citizen. This meant public arts funding and widespread community engagement.

A future left-wing government can learn a tremendous amount from these historical examples, by adapting the underlying principles. The core lesson is to use state power to de-commodify culture, build infrastructure for participation, and actively shift cultural power from corporate to community control.

A contemporary left-wing government’s cultural policy should be founded on the principle of cultural democracy – shifting the core question from “How do we get people to consume more high art?” (profit, commodity) to “How do we equip and empower every citizen to truly understand art and also become a creative producer of their own artistic culture?” (owning, production). The job is to de-commodify cultural expression and support a “second culture” from the ground up.

A possible policy framework

- Create a National Culture Fund

- Community control: funds would be allocated to local authorities, community foundations, and cultural councils with significant representation from local artists, trade unions, and community groups – funds need to be transparent and project-tied.

- Grants for participation: The fund would explicitly prioritise projects that enable participation (e.g., “Create a community mural”, “Start a housing estate choir”, “Run a digital storytelling workshop for warehouse workers”) over projects for a specific community or workplace audience.

2. Develop a “Cultural Mission” in Public Services

- Culture in the NHS: Support artists-in-residence in hospitals and community health centres.

- Culture in the Education System: Establish a national network of after-school arts clubs, free at the point of use.

- Culture in the Welfare System: Job Centres could connect people with creative skills development programs, reframing creativity as a valuable life skill, not a distraction from jobseeking.

3. Establish a Network of Public Creative Spaces

- Repurpose Empty Spaces: Turn empty high street shops, neglected public buildings, and unused office space into local creative hubs. These would offer low-cost studio space, workshop facilities (3D printers, pottery kilns, recording studios etc.), and meeting rooms – low cost cinema clubs with film discussions after screening.

- Digital Infrastructure: Create a national, open-access digital platform for sharing and collaborating, a non-commercial alternative to corporate-owned social media for artists.

4. Reform Education to Nurture Creativity, and Critical Engagement

- Art as Critical Thinking: Reform the National Curriculum to treat art, music, and drama not just as skills but as tools for understanding society, history, and power (akin to the pre-performance talks).

4. Democratise existing cultural institutions

- Conditional Funding: Tie public funding for major national institutions (museums, theatres, galleries) to demonstrable action in diversifying their boards, programming working-class artists, and developing deep, participatory partnerships with communities beyond their traditional audiences.

- Worker-to-worker programmes: Create a national scheme that facilitates partnerships between trade unions and cultural institutions, enabling group bookings, behind-the-scenes tours, and tailored talks that connect the art to the lived experience of workers.

The radical outcome of this approach is not merely more art, but the development of collective confidence and critical consciousness. When working people are given the means to tell their own stories, they challenge the dominant narratives that their lives are insignificant. This cultural empowerment is the essential groundwork for political and economic transformation, making the promotion of working-class culture the most radical project of all.

AM: Why is it important for culture to connect with people in other countries? How could internationalism be practiced more in culture?

JF: The international dimension is not an optional add-on: it is fundamental for three core reasons, rooted in class-based analysis of capitalism, and imperialism.

It reveals the systemic nature of exploitation: The “first culture” (the culture of the ruling class) often focuses on the “individual” detached from the spheres of work and society. This is also how the work of past artists is interpreted, through the lens of individualism. By connecting with the cultural expressions of working people in other countries, a powerful truth emerges: the experiences of precarity, alienation, and struggle are not local or individual, uncontrollable failures but global features of capitalism. A factory worker in Dublin, a delivery van driver in Berlin, and a garment worker in Bangladesh, though living vastly different lives, are all shaped by the same economic logic. Their stories, when shared, prove that the problem is the system itself, not a particular “tragic flaw” or the“fate” of a nationality or ethnic group.

It strengthens the “second culture” and builds solidarity: International connection transforms a local struggle into a global one. It provides moral support, strategic inspiration, and a sense of shared purpose. Learning about a successful tenants’ campaign in Barcelona or a creative strike tactic used by South Korean workers becomes a tool for everyone. This practice of solidarity is the crucial for a movement that seeks universal emancipation, not just a better deal within one country.

It is a direct antidote to capitalist globalisation: The ruling class is profoundly internationalist in its own interests. The cultural arm of this is a hegemonic, homogenised, consumerist “global culture” (Hollywood blockbusters, fast fashion, etc.) that erases local specificity and resistance. By building people-to-people, bottom-up international cultural connections, the working class creates a different kind of globalisation: one based on shared humanity, solidarity, and the richness of diverse experiences, rather than on exploitation and commodification.

International cultural connection is one effective way through with the working class learns that it is a global class with a common enemy and a common interest. This is already happening when working people read, watch, listen to cultural products from around the world that express their understanding of the world – e.g. Paul Robeson, Pablo Picasso, Käthe Kollwitz, Almudena Grandes etc.

How internationalism can be practiced more in culture

Such internationalism can easily be promoted in the cultural centres, reading group, workplace libraries etc, etc. Other ways to further and practice cultural internationalism:

- Create digital platforms for exchange: Build and fund non-commercial, cooperative digital spaces designed for international collaboration. For example:

- Community choirs can share recordings and sheet music, theatre groups can share scripts of plays about work, and photographers can collaborate on themed projects. etc.

- Virtual artist residencies where creators from different countries work on joint projects exploring common themes like migration, climate justice, or the future of work.

2. Reorient cultural institutions: Nationally funded museums, galleries, and theatres must practice internationalism from below. This means:

- Curating exhibitions and seasons not on “World Art” but on themes like “Portraits of Labour” or “Stories of Eviction: From Dublin to Detroit to Delhi.” I went to see the 2025 Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer Award exhibition in the National Portrait Gallery, and found that there was very little artworks showing people at work – most focused on ‘individuals and personal experience’. The proportion of themes should have been the other way around.

- Establishing permanent partnerships between community arts centres in different countries instead of just between large, prestigious institutions.

3. Integrate internationalism into grassroots projects: The local creative hubs and workshops we discussed should have an international component baked in:

- A writing circle in a Welsh mining town could have a dedicated project to exchange letters (or emails/videos) with a similar circle in a former mining region in Spain.

- A community history project in Liverpool documenting the city’s labour history could actively seek connections with a parallel project in Hamburg or Gdansk, port cities with shared experiences.

4. Support cultural exchange as a form of solidarity: Fund trade unions and community groups to facilitate real-world exchanges:

- Instead of just sending delegates to formal meetings, support artists and cultural activists to travel and share skills, strategies, and stories with their counterparts in other countries. A muralist from Belfast could work with a community in Colombia; a playwright from London could workshop a new piece with actors in Johannesburg.

The ultimate goal is to create connections that exist outside of the market and the state-sponsored nationalism of the “first culture”. And so, cultural practice can become a direct form of political education and organisation, furthering the solidarity needed to heighten the understanding of common humanity and to confront the inhumanity of global capital.