By Alan McGuire

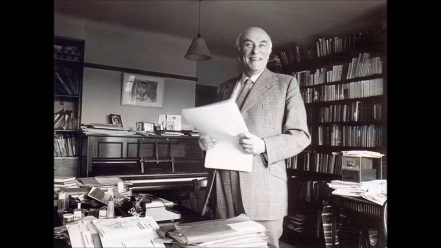

Ben Lunn is a composer and organiser whose work is rooted in working-class life. Born in Sunderland, his projects engage directly with themes of class, disability, and regional identity, making a space for voices often excluded from contemporary classical music.

Alongside his own compositions, Lunn is a passionate advocate for others, curating radical concert programmes and reviving the legacies of politically committed composers.

“His work extends the palette of sounds that can be brought into contemporary classical music, redefining both modern composition and concert-hall inclusion.” – Alan Morrison, Rhinegold.co.uk

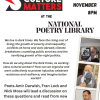

In this interview, we talk about his ongoing work around the communist composer Alan Bush, the political potential of music, and upcoming events that aim to reclaim the concert hall for the many.

AMcG: Why do you think Alan Bush has been marginalised by mainstream classical institutions, and do you see signs of that changing?

BL: There are a multitude of factors. Firstly many composers of Bush’s generation are not performed today as much as they were. This is particularly endemic for composers who rose to prominence in the 30-50s, though it has happened to many composers because in Britain there is not enough exploration of composers who fall into the awkward gap of ‘classics’ and ‘modern’. But for Bush in particular, his politics saw him blacklisted in his time – which officially ended thanks to the intervention of fellow composers like Ralph Vaughan Williams – however how true this was is very unclear. Similarly, because his anniversary has almost no recognition outside of the WMA, it is unlikely this trend will change.

How did Bush’s politics shape not just the themes of his music, but the way he composed and collaborated?

It is hard to say this concisely, however there were a few strands. Firstly, he was eager to make his music speak with a British voice. This meant drawing upon traditional idioms like British folk songs, or the harmonic language within them and reconstructing them in a new way. Another, in a more didactic manner, was in the choices of thematic materials for works, like using the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt to inspire his first opera Wat Tyler or the Guyanese fight against British colonialism in his third opera The Sugar Reapers. A third, and important element for the WMA, is the role of amateur music-making. This included creating works that could work in educational settings, but most importantly, they were rarely neutral. They were often a route into politics, or a route into music. The creation of the Left-Wing Song Book with Randall Swingler is one great example of this.

Which of Bush’s works do you feel best represents his legacy, and why?

Once again, a very hard one to say briefly but I’ll focus on a few favourites of mine:

Piano Concerto – Written in 1937, this incredible work is about an hour in length, and initially functions as a piano concerto but is interrupted by a chorus who make us consider what do we actually gain from art? – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9oq8Qs2FPwE (performed by Rolf Hind)

Lidice – The horrific actions the Nazis committed against the village of Lidice, wherein they destroyed everything and everyone within the village, horrified people across the globe. Composers responded to the horrors, including Martinu’s Memorial to Lidice. Alan Bush, working with his wife Nancy, wrote a truly moving choral work simply called Lidice portrays the people of Lidice as not victims, but people who died on their feet and for that the memory of the people of Lidice lives on. – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JgEXW2UogF0 (Londinium Chamber Choir)

Men of Blackmoor – This is my favourite of his four operas, partly because I am biased as it is a rare opera about the North-East of England. The opera shows the life and challenges of people in the imagined pit village of Blackmoor. I’d highly recommend the radio broadcast of the opera available on YouTube as it is a fascinating work. – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIlYo-W5VXQ&t=2129s&pp=ygUJQWxhbiBCdXNo

What were your priorities in curating the programme of events for Bush’s 125th anniversary?

Ultimately, as an organisation founded by Alan Bush, we in the WMA felt it was simply our duty to celebrate him and honour his legacy. So, we knew we had to do something. Building from this, we wanted to make something that attempts to show the breadth of Alan Bush – be it his incredible body of choral works, piano works, or his theoretical works. This combined with ideal partners to team up with helps us to celebrate as the fascinating individual without any baggage, but letting the music and ideas ring out.

What do you hope audiences — especially those unfamiliar with Bush — take away from these events?

My personal hope is these events will not only open up audiences to the wonderful music and ideas of Alan Bush, but also demonstrate that the ideas of Bush are not only relevant today, but composers and musicians can draw upon this approach themselves today, making it a living and breathing approach to art.

How has the mission of the Workers’ Music Association changed over the decades — or has it stayed fundamentally the same?

In our nearly 90 years of work, our mission has remained the same – bringing all music to the working class, and giving music a working-class voice. However, like many organisations of our nature, capacity is what has changed. With our celebrations this year, 2025 is our most animated year in a long time, and we are aiming to follow up next year for our 90th celebrations, which should hopefully rebuild our work and draw in more members so we can do bigger and bolder things!

What role does the WMA play in connecting today’s musicians with the radical cultural traditions of the past?

There is firstly an educational element. This has included us publishing articles discussing radical music traditions, or the role of music during periods of revolution. Similarly, connecting with radical cultural traditions have never been restricted to Britain or Europe. This included publishing songs from Vietnam during the Korean War, this included Ewan MacColl’s famous Ballad of Ho Chi Minh. Every point of revolution has been followed by a cultural upswing as artists and people use the arts to make sense of their hopes and the situation around them, and we have tried to continue celebrating this, alongside celebrating the wealth of musical history.

Do you see a resurgence of interest in politically engaged music among younger composers and audiences?

Yes, however it can be argued the political vision isn’t always as clear-cut as figures like Alan Bush. However, we’d be foolish to admonish people for this clarity, as ultimately it takes time to sharpen political points. Realistically we should be overjoyed, particularly at how music is filled with a wealth of rebellion and politics, mostly in response to the horrors in Gaza, and hopefully if artists can see the vision of composers like Alan Bush they can sharpen their political intent to move beyond to just reaction but into something even more aspirational.

How can people support or get involved with the WMA’s work going forward?

We depend on our members, are a democratic organisation, so if you believe music can be used for political good we want you to get stuck in! You can find out more about us at our website https://workersmusic.co.uk/ and we hope you can join us soon!