In this edition of Our Culture, Keith Flett examines how global capital shapes food and drink, from multinational brewers to fragile supply chains under climate pressure. The article is followed by some questions from series editor Alan McGuire, where Keith explores what a left response could look like in practice.

The global brewer Heineken’s latest results showed a decline in sales in the US due to what it called “trade uncertainty”, otherwise known as Trump. But all was not lost. Sales rose in Africa and the Middle East, and Heineken simply hiked prices to compensate. The company also reported a 50 percent increase in UK sales of its Spanish lager Cruzcampo, which is in fact brewed in Manchester.

In other words, global business has well-practised ways of maximising profits at the expense of both producers and consumers.

At the same time, Unilever is reported to be considering selling off its ice cream division, which includes Ben & Jerry’s and Wall’s, and, somewhat confusingly, Marmite as well.

In some countries, the operations of global giants like Heineken and Unilever have unionised workforces, and in certain jurisdictions they are subject to regulations over what goes into their products. It is reasonable to assume, however, that these factors are not what mostly keep CEOs awake at night.

Wider challenges do. Probably the biggest is the issue of raw supplies needed to keep these global businesses running. Here the aim is to pay producers, usually located far from Western European or US headquarters, as little as possible.

Climate change has intensified this pressure. Prices for raw materials such as coffee and cocoa have soared, while olive oil prices remain sky high. Whether it is beer or food, global business has ways of responding. This includes a raft of climate initiatives carefully laid out in annual reports. While box-ticking may help public image, protecting the bottom line requires more robust measures.

A key objective of the global producer is to maximise profits by sourcing the cheapest possible raw materials, while still ensuring the product sells and appears to be of acceptable quality. Enormous effort goes into quality control so that a beer or food product tastes the same wherever it is consumed.

So how can the apparently relentless advance of big food and big beer be challenged?

One answer lies in producer cooperatives, some of which already exist, uniting to secure fair prices for labour involved in producing coffee beans, hops, and other raw materials. These initiatives can limit the exploitative logic of global capital, but they are not enough on their own.

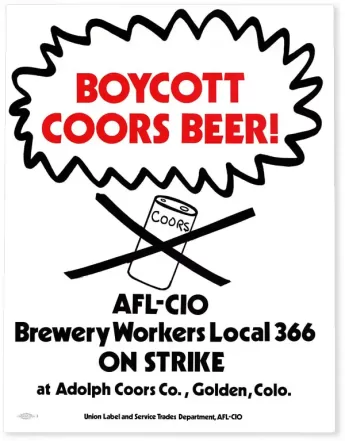

A broader political focus is needed, particularly through engagement with the global struggle around climate change. This means putting people before profit in ways that move beyond slogans. It requires movements that unite producers and consumers through political campaigns, boycotts of exploitative goods, and the active promotion of alternatives.

This work is very much still in progress.

AM: In what ways does capitalism stop working-class people from fully enjoying food and drink, and how does corporate pricing shape everyday experience?

KF: The ongoing cost of living crisis means many people cannot afford to eat and drink out. Beer from a supermarket is far cheaper than beer in a pub, even Wetherspoons except for cask beer. As a result, drinking at home rather than socially has become the norm for many.

The tax regime between supermarkets and pubs could be equalised, but so far no government has been willing to take on Tesco and Sainsbury’s.

AM: The Carlisle State Management model improved the experience of drinkers. Could something similar be reintroduced?

KF: In 2025 it would require a great deal of work. The 1945 Labour Government planned state pubs and a state brewery for the New Towns, but they lost office before this could be implemented. Even if it had happened, many people seeking local beer in 2025 would probably have disliked the result.

AM: Community-owned pubs seem like a strong alternative to profit-driven chains. How could government support them?

KF: CAMRA consistently argues for reduced business rates and taxation so independent pubs can operate at a normal profit. Without this, community ownership struggles to survive.

AM: What could a left-wing government realistically do to improve food and drink for ordinary people?

KF: Encouraging union membership and recognition for hospitality workers would be a significant step forward, something the Employment Relations Bill at least gestures towards.

However, many of the dominant players in food and drink are global corporations. Meaningful regulation requires cooperation between unions and social movements across borders. This happens occasionally in some sectors, but rarely in hospitality.

AM: How would democratic planning, worker-run production, and public ownership change our relationship to food and drink?

KF: UK examples are small-scale. Abbeydale Brewery in Sheffield is employee-owned. That said, the experience of the 1974 to 1979 Labour Government suggests worker cooperatives can struggle, particularly when the economics do not stack up.

AM: Capital operates globally. How can the left build an effective international strategy?

KF: One of the most effective current tactics is boycotts. This includes beers produced by companies with poor employee relations, such as BrewDog, Omnipollo, and Founders in the US, as well as breweries that trade with Israel, although this information is often difficult to obtain.

The general point is that an ounce of action is worth a ton of theory. This week, Unite members at the Guinness brewery in Belfast, which produces Guinness Zero, are taking action that is likely to lead to Christmas shortages. Publicity, let alone solidarity, has been minimal.

Starting where something is already happening and building from there matters. Plans for doing things differently are important, but moving beyond ideas is the real challenge.

One positive example is the Scottish brewer Brewgooder, which has produced a solidarity beer with a Palestinian craft brewery. It is currently on sale in Co-op stores across the UK, with proceeds going to medical aid. Just as importantly, it is actually a decent beer

Read the rest of the editions from the Our Culture series:

Culture as Class Struggle: An Interview with Jenny Farrell

Our Culture: RIP British Working-Class Cinema (1935 – 2025) by Brett Gregory

Our Culture: The Uncomfortable Truth About Public Libraries

Our Culture: Breaking through the Class ceiling with bread and roses

Our Culture: Games and Class Struggle – with Scott Alsworth

Our Culture: Prize-winning Poetry Only Please! with Andy Croft