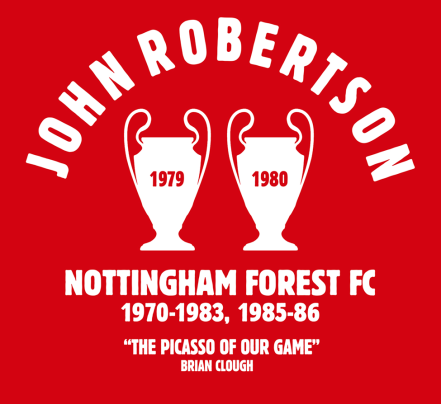

The Picasso of our game

By Mark Perryman

OK England’s relationship with European football didn’t exactly begin well, in1955, the first European Cup. Chelsea, the First Division champions, are banned from entering by the FA, as the competition is not considered as in the best interests of English football.

The competition itself is a knockout competition, two legs home and away, league champions only, no seeding. The classic FA Cup model before it too was bastardised, but that’s another sad tale to tell.

The first five years marked by dominance – Real Madrid win all five competitions 1955-1960. The birth of a popular, Europeanised, football culture. The 1960 Real Madrid v Eintracht Frankfurt final, Hampden Park, crowd of 127,671, 7-3, BBC televised it, across Europe an estimated 70 million watched the game (terrestrial, no satellite TV). The greatest football match ever? And expansion, 26 nations league champions entered, up from 16 in 1955.

And tragedy too. In 1958, the Munich air disaster, Manchester United ‘s plane crashes on the way back from playing Red Star Belgrade in the quarters. Liverpool – yes Liverpool – lend United players so they can complete their season. The following European Cup, in another act of footballing solidarity, United are invited by UEFA to enter. No such compassion from their own FA mind you, who quite extraordinarily refuse to allow United to do so.

Through the 1960s the competition continues to expand. The champions of Norway, Malta, Albania. Iceland all join the competition. In 1966 Yugoslavia’s Partizan reach the semis, the first team from Communist Eastern Europe to do.

In 1966-67, the champions of the Soviet Union enter for the first time. Celtic win against Dukla Prague from (East European Communist) Czechoslovakia in the semis having beaten Yugoslav (ditto) side Vojvodina in the quarters. In the final, they beat previous champions Inter. The first ‘British’ side to reach the final, and win. But this was of course an entirely Scottish victory, shaped by the sectarian divide – though famously the entire Celtic team was born and grew up in Glasgow. In the first 12 years of the competition there had been Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and now Scottish champions of Europe.

And in 1968 Man Utd, become the first English Champions, winning the trophy, after extra time. At Wembley, incredibly exactly ten years on from Munich.

United’s goal-scorers in the Final? Bobby Charlton (2), Brian Kidd and George Best. The core of the team was Bill Foulkes, David Sadler, John Aston, Nobby Stiles, Shay Brennan and Tony Dunne. As Eamon Dunphy puts it in his superb book on Matt Busby A Strange Kind of Glory: “all had graduated from Busby’s School of Excellence, the car park at Old Trafford.”

Today United’s support comes from all parts of the British Isles, not to mention the entire globe on a national and international scale that their latter-day rivals, Arsenal, Chelsea and Manchester City, and in recent years, more successful too, can only dream of is put down to a better marketing operation. But its origins lie not in the antics of marketing gurus, instead in the national outpouring of sympathy following 1958 and a nationwide celebration of recovery via victory in 1968 that all but the most embittered would join in.

I can still remember my cub scout Saturday morning football side the autumn after all turning up in red shirts, white collar and cuffs. Not ridiculously expensive bri-nylon replica shirts plastered with sponsors’ logos in those days, but young boys pestering our parents all summer long to find a top that would make us look like, if not play like, our heroes, in deepest Surrey!

But it wasn’t all good. By the 1970s a growing reputation for English hooliganism was crowned by Leeds fans, when in 1975 their club reached the European Cup Final, only the second English club to do so. They filled the stadium with a riot following defeat by Bayern Munich. Other countries had equally bad reputations for football hooliganism domestically – the difference was England exported it.

However happier news was to come. 1977, Liverpool beat Borussia Mönchengladbach in the Rome final. Foreign players? Joey Jones Wales, Steve Heighway – Republic of Ireland. English manager – Bob Paisley. The first of six consecutive wins by English league champions.

John Williams, Liverpool fan and author of the definitive social history of the club, described the post-match celebrations:

The extraordinary party in Rome after the 1977 final involved Reds supporters and the players together. These groups were still broadly drawn from the same stock, drank (and got drunk) in the same pubs, had pretty much similar lifestyles and diets, and footballers had not yet moved into the sort of wage brackets that later had them sealed off behind tinted-windowed cars the size of small, armoured trucks.

Liverpool won a second consecutive European Cup in 1978 and again in 1981. But in between was surely the greatest European Cup achievement of all.

1978-79 Brian Clough’s Nottingham Forest knock out holders Liverpool in the 1st round. Forest win the first of two consecutive European Cups, with three foreign players, all Scots, Kenny Burns, John McGovern, John Robertson, and two more Scots as unused subs plus Northern Ireland’s Martin O’Neill.

1979-80 Forest retain the European Cup – their unique record is that they have won the European Cup more times than the domestic league. Forest’s team in the final against Hamburg had three foreign players, all Scots, plus one sub, and an English manager.

And John Robertson, one of those Scots, was central to this incredible achievement. 243 consecutive games for Nottingham Forest, December 1976 to December 1980. In that amazing run he scored the winner for Forest in the 1978 League Cup Final; was key to the team winning the 1977-78 First Division; provided the cross that Trevor Francis put away to win the 1979 European Cup; and the winner to retain it in 1980.

Daniel Taylor, football writer and Nottingham Forest fan, sums up the magnitude of the achievement John was such a major part of, perfectly:

Forest’s rise to the top, lest it be forgotten, took place when only the champions of each country and holders could compete in the European Cup. There was no safety net of multiple group stages to guard against the occasional defeat here and there and the legacy, thirty-five years on, is that Nottingham had won the competition more times than London (now equalled), Paris, Berlin, Moscow and Rome – with a combined population of 30.4 million – altogether.

It took Manchester United, champions in 1968, another 31 to win the European Cup for a second time – Ferguson’s win in 1999 coming at his fifth attempt – and it was 2012 when Chelsea finally notched one up for London. Arsenal, Tottenham and all the others are still on the waiting list.

And what we have now is ‘The Champions League.’ In a feat of Newspeak that would do Orwell proud, UEFA has rewritten the entire history of the European Cup as The Champions League when until 1992-93 it wasn’t. A ‘champions’ league which isn’t any such thing. ‘Champions and Rich Runners-up League’ might not attract such rich sponsors, yet stands as an infinitely more accurate description.

On what possible basis can a club that has finished 4th, 5th or even 6th be described as a ‘champion’? Wealth, of course. The purpose of replacing the European Cup with a league format was absolutely explicit. To protect and multiply the wealth of what are what are already the wealthiest clubs and leagues.

A knockout competition, teams drawn randomly to play each other, no seeding, home and away legs, threatens all of this. Tough! It’s called sport.

And what this means is that John Robertson’s achievement, a player for a club outside the very wealthiest, of two European Cup Winner’s medals will almost certainly never be repeated. And that is the absolute antithesis of what a European Cup should be about.

John Robertson tribute T-shirt available from Philosophy Football