Vienna City Hall Christmas Market

By Dennis Broe

Vienna has been voted the world’s most livable city for a long time, and although it still maintains that tradition, linked to its socialist and social democratic past, the Viennese ship of state, at its high season of Christmas in 2025, is sturdy but springing leaks.

The tourist overflow, which has plagued European cities such as Barcelona and Venice—reaching its decadent peak in that city last summer when Amazon’s Jeff Bezos bought the city for a week—has now hit Vienna. Ships dock on the Danube alongside the city centre and the tourists come streaming out, the tours so prominent that, just like the overbeaten path in Venice from the Realto to San Marco, manoeuvring in the zentrum, the centre of the city, becomes a matter of sidestepping the omnipresent tour guides and their crowds.

The other reality underlying the ever more gorgeous Christmas lights, especially those in front of the Christkindmarkt, the Christmas Market at the city hall and the Schonbrunn Palace is, as everywhere else in Europe, the rapidly deteriorating economy. This year Austria, known for its neutrality, instead took sides in the Ukrainian conflict and stopped buying Russian oil and gas, replacing it with American fracked gas at four times the price.

The city still has the best transport system in Europe, including a 16-minute cheap train, with wifi, that whisks visitors from the airport to the centre, an efficient and easy to manoeuvre with a subway system as well as trams above ground, which offer magnificent views of the city.

Vienna is not quite a global city like Paris and London, but it becomes more popular every year and besides the cruises, it is the destination point for visitors from all the countries to its East, harking back to its place in the Hapsburg Austro-Hungarian empire.

The city has been traditionally critical of the American presence, celebrating as its Independence Day the date in 1955 when American troops left, but celebrating this not as independence but as ‘Neutrality Day’, in line that same year with the Bandung Conference of non-aligned Global South nations, also asserting their attempt to maintain a path outside, or maybe alongside, U.S. global hegemony. This moment is commemorated in the House of Austrian History Museum which tracks the nation’s development from the end of World War I.

Gary Cooper’s pig-ish American vs. Audrey’s cello-playing young French woman

The Metro, the city’s cinema repertory, featured as part of an Audrey Hepburn retrospective Billy Wilder’s 1957 Love in the Afternoon, which took a satirical look at the American-European relationship in the 1950s. Hepburn, a twenty-something Parisian cello player, attempts to humanize Gary Cooper’s much older, crass businessman/philanderer, interested only in making money and bedding women, and it is an uphill battle – one that reminds us of our own seducer/scam artist-in-chief and his minions, as the Epstein files remain a redacted mess.

In Epstein-related cinema, the Metro also boasted a program of Arthur Schnitzler adaptations, including an Austrian and American version of Schnitzler’s Dream Story, yes, a psychologically complex laying out of male anxiety at the inability to dominate women but also, particularly in Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, a laying bare of naked power relations as the Viennese male elite have their way with women from the street in just a slightly more ‘sophisticated’ version of Epstein Island.

Perhaps the strangest manifestation of the shifting economic winds, as in neighboring Germany even Volkswagen closes its plants for lack of cheap energy, were the conflicting emotions in the Staatsoper’s Fidelio, Beethoven’s only opera written in the wake of the French Revolution as the changes wrought by that moment are sweeping Europe.

By far the strongest part of the opera is the music, not only in the first and second act overtures, but also in an extended moment before the raising of the curtain for a chorus coda celebrating, in Victor Hugo Les Misérables-mode, the return of justice engineered by the wife of a prisoner in a Spanish dungeon.

This is Beethoven in soaring Ode to Joy (the European anthem) and Ninth Symphony mode. The music is extraordinary in its announcement and celebration of the crumbling of the ancien regime and the establishment of a more equal system, given astounding voicing here in the conducting of the Cleveland Symphony’s Franz Welser-Most and the full-throated emotion of the Vienna Philharmonic.

Unfortunately, this spirit of European communalism is every day in the process of being betrayed, as the old continent abandons its social welfare state in favuor of becoming simply a war machine, bent on its own self-destruction by leaders utterly out of touch with the needs of their people.

Austria is ruled by a right-wing conservative coalition, but the city of Vienna in its exhibitions, continues to question the nation’s links to a troubling past. The Welt (or World or Ethnography) Museum’s Colonialism on the Windowsill is a distillation of how the flora and natural resources of Latin America, Asia and Africa were first ‘discovered’, and then how these natural healing properties were ‘refined’ for global consumption and commodification by Western drug companies.

Prominent among the plants on display is the Spider Plant, with its green flowing leaves or tentacles, in Africa known for its healing powers, especially for pregnant women and babies and much admired by Goethe.

One of the grandest museums in the city is the Dom Museum, which houses the collection of the Saint Stephen’s Cathedral and stages fascinating exhibits. This year is Alles in Arbeit, translated by the curators with the too-arty title ‘Works in Progress’, but which might better be translated ‘Always at Work’, since it recounts several centuries of labour history in painting and graphic works.

The Merchant of Venice is a modern photo comment on Shakespeare’s play with an African posed selling handbags, a way of these modern merchants creating a livelihood in a city hostile to their presence. A section of the exhibit focuses on women’s work: in a factory in the 1902 The Feather Makers; in the forlorn gaze of a weary female worker with eyes lowered by Kathe Kollwitz; and in the juxtaposition of a poster from a worker’s collective with the slogan ‘A Woman’s Work Is Never Done’ linking domestic to factory labor to a 16th Century Madonna and Child with a weaver in the background, emphasizing Mary’s unpaid labor.

Finally, there is John Heartfield’s Finest Products of Capitalism, 1932, with a tired husband working himself to the bone to buy the elaborate dress and veil his wife, transfixed on a platform next to him, wears, both victims of an unending consumerist nightmare.

The exhibit at the Architecture Museum, Abundance Not Capital, focuses on the Indian architect Anupama Kundoo who, though mastering the imposing European modernist work of a Corbusier or Rem Koolhaus, chooses instead in her country to build sustainable low-to- the-ground structures which showcase native materials including clay and terracotta and which are designed to cultivate a more contemplative, less frantic, pace of living.

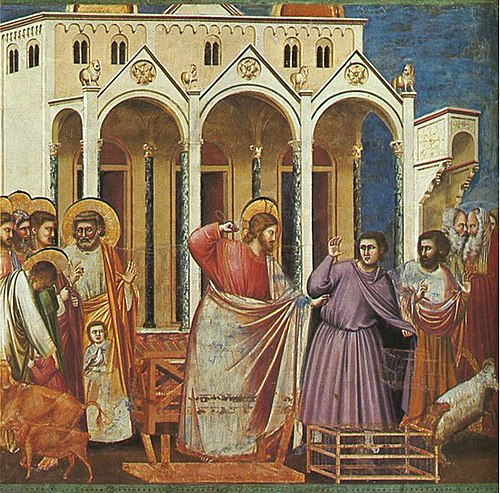

Two exhibits explored turn of the last century trends in art. The first, the Albertina’s Gothic Modern, is a stunning look at how artists, in a period where European colonialism was dividing the world and leading to a grand conflagration, embraced the pestilence and warfare of the late medieval work of Durer and others to represent their own era.

The stars here are Kathe Kollwitz (again) in Death and the Woman, emphasizing the frail hands and face of an old woman’s mangled body; Edward Munch’s depiction of a man hobbled with depression in Melancholy as well as his expressionist town with tortured buildings leaning on each other for comfort in Lubeck and Otto Dix whose Skull (War) with worms crawling out of the openings of a gaping head signal Dix’s disgust with the killing fields of the First World War.

Skull (War) by Otto Dix

Less successful was the Leopold’s Occultism with some striking and comprehensive images of the fetishizing of the spiritual and the spirt world in turn of the 20th century art. A chart tracked where this fetish led, culminating in, on the one hand, vegetarian and alternate lifestyles but, on the other, in abstraction (Kadinsky) and fascism, a la Hitler’s fascination with the same currents. The exhibit though failed to illustrate either of these directions and would have been much better following them to their (logical?) conclusion.

The Freud Museum’s Documents of Injustice traced the systematic looting of not only Freud but the material possessions of his family and extended family by the Nazis. He and his brother had to buy their way to freedom, abandoning most of their accumulated wealth and having to leave their three sisters, all dying either just before being shipped to or in the concentration camps.

The exhibit makes us aware that though they were genocidal murderers, the Nazis were also petty thieves whose system was designed to confiscate every bit of loot they could get their hands on. The Nazi state administration in Austria, at one point, had to order random looting of the Jewish population halted because too much money was being stolen by private individuals and instead that money was needed to systematically sustain the war machine of the Nazi state.

More injustice was revealed by the Jewish Museum and this regarding Vienna’s first musical family, the Strausses, in Johan Strauss—Classified Top Secret. Behind a black veil, accentuating the hidden quality of its revelation, lies the record book of the marriage of Johann Strauss’ great-grandfather, where he is listed as Jewish, a fact buried and concealed by the Nazis.

Pull on that string and the whole Aryan supremacy racket unravels as the writer of The Blue Danube and Tales From the Vienna Woods has not the ‘racial purity’ the Nazis were at pains to protect. A Hollywood film, The Last Waltz (1938),playing at the Metro, mythologized the creation of the two pieces as part of an affair the composer had with a tempestuous actress, a part right out of the oeuvre of Marlene Dietrich, though here played stunningly by Milija Korjus, with La Dietrich’s most famous director Joseph Von Sternberg working (uncredited) on the film.

Finally, and perhaps most prescient, was the Burg Theatre’s production of the English playwright Carol Churchill’s 2004 Copies, about a young man who is ‘cloned’—remember that word?—and tries to find out who he is by quizzing his father.

We are living in an age where, because of AI, there are nothing but copies, to the point where the word clone is now retired with no longer the frisson it once had because we encounter ‘clones’ everywhere we turn.

Next to be retired in this age is the word ‘authenticity’, a key concern in Churchill’s play. The young man’s anxiety achingly staged at the Burg, the preeminent theater in the German speaking world, is a snapshot of a bygone era before the AI ‘miracle’ where a single copy induced anxiety, rather than today’s world where what is left of the dynamism of the U.S. economy is built on releasing as many copies as possible into a world which, far from clamouring for them, remains skeptical at best of their efficiency and utility.