By Jenny Farrell

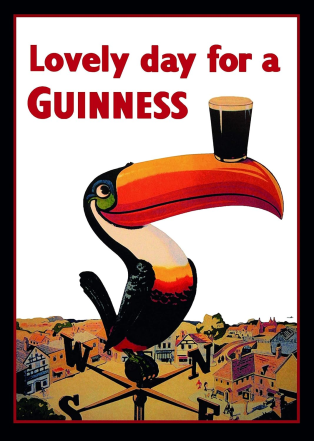

Fun fact: Guinness, the quintessential Irish drink, exported around the world, originated in the working-class pubs of early eighteenth-century London. Known as porter, this dark beer was invented as an affordable, nutritious, and consistent alternative to the custom-mixed blends patrons often bought. Its name came from its immense popularity with London’s dockworkers and market porters. Brewed with charred malt and extra hops, porter was durable enough for long sea voyages, making it a perfect commodity for Britain’s naval empire.

When this popular London import reached Dublin, it was an instant success. Arthur Guinness, who had bought a disused brewery at St. James’s Gate in 1759, was not the first local porter brewer – Dubliners like James Farrell, guided by the London-trained brewer John Purser, were already producing it by the mid-1770s. Guinness adapted quickly, brewing porter from 1778, dropping ales by 1799, and from the 1820s, his successors were marketing stronger versions as “stout porter” and later simply “stout.” At any rate, by 1779 Arthur had secured the lucrative Dublin Castle contract, ensuring his brewery’s growth. Guinness’s real legacy was copying porter on a large scale.

Born 300 years go, Arthur Guinness (1725-1803) was a man of indigenous Irish roots whose family had converted to Protestantism. Though not part of the privileged elite, he belonged to a striving middle class that used education, strategic marriages, and commercial acumen to advance within British colonial society. He identified as a Protestant Irish patriot – supportive of Catholic emancipation and loyal to Ireland – yet remained a pragmatic businessman who worked within the system to achieve success.

His life unfolded against the backdrop of the Penal Code, a comprehensive system of oppression designed to enforce the colonial control that subjected the Catholic majority to political powerlessness, economic strangulation, and social humiliation. Laws barred Catholics from voting, owning valuable property, receiving an education, or practicing their faith freely, reducing them to wretched serfdom. This crucible of oppression forged a resilient, underground Irish identity, with clandestine resistance groups, culture, and learning preserved in secret by hedge-schools and priests.

Guinness’s commercial ambitions were constrained by England’s ruthless colonial policy, which systematically dismantled Irish manufacture, trade, and industry through targeted legislation, such as the notorious Wool Act and others. Prosperous Irish exports like wool, cattle, and manufactured goods were deliberately stifled to eliminate competition, crippling the economy and enforcing subservience. A corrupt and unrepresentative Irish Parliament, controlled by a landed oligarchy and English patrons, served as a mere instrument for London’s will. The result was an economic structure designed to depress the vast majority of the population to bare subsistence, where tenants and labourers survived on a precarious diet of potatoes while producing food and raw materials for export. Famine was frequent. As Jonathan Swift’s savage irony highlighted, this system allowed landlords to “devour” the people, creating a nation perpetually on the brink of starvation.

Swift, a key figure of the Enlightenment, employed reason and satire to lampoon the colonial system as cannibalistic – most famously in A Modest Proposal (1729) – and outlined the imperative of an indigenous Irish economy in works like The Drapier’s Letters (pamphlets published between 1724-25, the most famous fourth letter: A Letter to the Whole People of Ireland). Writing under the pseudonym of a simple shopkeeper, he created a relatable national hero who galvanised public opinion against exploitative measures such as William Wood’s inferior copper coinage. Swift thereby contributed to forging a national Irish identity, appealing across class and sectarian lines to a “whole people of Ireland”, united against a common oppressor. In Gulliver’s Travels (1725), Swift even anticipates a successful revolution in Ireland. This is seventy years before the United Irishmen!

Both Swift and Guinness were part of the Protestant establishment, but their approaches diverged significantly. Swift acted as a critical conscience, railing against colonial rule. Guinness, by contrast, embodied the benevolent patriarch. His philanthropy – providing healthcare, supporting hospitals like the Meath, co-founding Ireland’s first Sunday School and in later generations offering pensions and housing – was both genuine in its care and pragmatic in its design. A healthy, loyal workforce was a productive one. While Swift shamed the elite for failing Ireland, Guinness offered a model of paternalistic care within the existing system, providing private solutions to public problems without challenging the underlying inequalities.

Guinness practiced patriotic pragmatism. He opposed the Penal Laws and supported freer trade and legislative independence for the Irish Parliament in the 1780s. As a member of the “Kildare Knot,” a provincial branch of the larger Order of the Friendly Brothers of St. Patrick, which adorned itself with green ribbons and Irish emblems, he identified firmly as Irish. Yet, he used networking, council membership, and influence within the system – reform, not revolution. He did not support the United Irishmen’s epic uprising in 1798; his vision was one of gradual electoral reform. He benefited from the very system that generated the grievances behind the rebellion, and his progressive ideals remained sentiments rather than catalysts for change.

Guinness’s philanthropic efforts were rooted in the Protestant ethos of “good works.” He made significant loans to charitable institutions, refused repayment, and served as unpaid treasurer of the Meath Hospital for decades. Subscribers to the hospital could send patients for treatment, a practice that benefited his workforce and foreshadowed the brewery’s later formal clinics. This approach combined charitable intent with enlightened self-interest, fostering goodwill and social respectability while addressing genuine need within the constraints of the time.

Arthur Guinness’s legacy is thus dual: he was a product of the colonial system whose actions alleviated some of its harshness, even as he ultimately upheld its structures.

Shock fact: from 1799 to 1939, Guinness was Ireland’s largest private employer. Today, however, the brand is owned by Diageo – a British multinational created in 1997 through the merger of Guinness plc and Grand Metropolitan. In the process, Guinness’s once-vaunted worker welfare – housing, healthcare, pensions – was phased out by the late 20th century. Diageo’s record since has been one of cost-cutting, brewery closures, and job losses. It even sat on the board of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), helping to shape corporate-friendly tax and liability laws, before quitting under public pressure in 2018. What was once a paternalistic brewery at the heart of Dublin is now an anti-working-class multinational that prioritises shareholders.