A Brief History of Sentimentality, Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-1-3994-21881-1, £20

Soft is both a hard and a slippery book to review. It is interesting, though, to observe Ferdinand Mount, third Baronet and old Etonian, writing learnedly and occasionally amusingly on such a theme. According to its blurb, Soft treats us to:

…the millennium-long history of emotion […], the shifting importance societies have placed on empathy for the misfortunes of others […and the…] corresponding sentimental revolution that has fuelled these great political turning points.

The author appears to have taken at least some of his ideas from C. S. Lewis’ The Allegory of Love (1936), particularly the following passage (which he quotes):

Real changes in human sentiment are very rare – there are perhaps three or four on record – but I believe they occur…

Accepting the diktats of stuffy old ‘Jack’ Lewis – for most of his life a confirmed bachelor – on the subject of romantic love seems a bit “rich”, but there we are. Mount identifies three epochal shifts in sensibility, circa 1,100 A.D., 1740 and 1963 (!). The first occurred in Languedoc, France, with the arrival of the troubadours and, a little later, the “trobairitz” (identical, only girls). These all celebrated courtly love. We are informed that “the great classical authors had no elevated notion of love”, yet a little additional research might have turned up, for instance, the Greek poet Sappho (c. 630- c.570 B.C.) who did also write about heterosexual relationships, dishing out the lurve with a ladle:

If I meet/ you suddenly, I can’t/ speak -my tongue is broken;/ a thin flame runs under/ my skin; seeing nothing,/ hearing only my own ears/

drumming, I drip with sweat;/ trembling shakes my body/ and I turn paler than/ dry grass. At such times/ death isn’t far from me.

(from Fragment 31, translated by Mary Barnard).

By way of contrast, Mount cites William of Aquitaine’s Ab la dolchor del temps novel (“rendered into modern French”):

Ainsi va-t-il de notre amour

Comme de la branche de l’aubepine

Tant que dure la nuit sur l’arbre,

Elle tremble a la pluie, au gel,

Mais l’endemain le soleil luit

Sur la feuille et le rameau vert.

or, in A.S. Kline’s English translation:

This love of ours it seems to be

Like a twig on a hawthorn tree

That on the tree trembles there

All night, in rain and frost it grieves,

Till morning, when the rays appear

Among the branches and the leaves.

….which, he assures us, “sounds even better in the plaintive, metallic Occitan”. This reader did, sometimes, find himself rather wanting to “deflate” Sir Ferdinand as when, deeper into the narrative, the author reminisces “as a student in Freiburg sixty years ago, I cycled across the Rhine to nearby Colmar where the altarpiece […of Grunewald’s “Crucifixion”…] now hangs.” One is caused to wonder whether he felt either need or requirement for a bridge?

Mount’s prosaic style is highly discursive. We are regaled in Chapter One (“The First Sentimental Revolution”) with the description of a thirteenth century competition in religiosity between England’s Henry III and France’s Louis IX (hingeing on which was the more pious, the Sermon or the Mass) and featuring the bequeathal in his will of Henry’s heart to the Abbey of Fontevraud.

A thinly-linked disquisition on that “extraordinary” monastic house and its founder, Robert d’Arbrissel, follows. The rehearsal of so much medieval, ecclesiastical scholarship is either “fascinating” according to your taste, or “wearisome”, according to mine. The chapter ends, somewhat whimsically, with the long-reigning Henry being praised as a prototype wielder of “soft power”. Please remember to tell that to the defeated insurgent, Simon de Montfort, with his own severed testicles shoved somewhat unchivalrously into his dead mouth following the (1265) battle of Evesham! Mount is unafraid to wheel-out the ‘Python’ Terry Jones’ seminal Chaucer’s Knight (1980) even though its central conclusions are antithetical to his own. The problem with being “wide-ranging” is that one is also quite likely to be “all over the place”.

If we are to believe Soft, sentimentality began to die out with The Reformation, when hard-faced men rapaciously expropriated monastic land (and the attendant infirmaries for the poor). This drift was, we are told, exacerbated by Puritanism. The pejorative adjective “maudlin” (inspired by the “excessive” tears of Mary Magdalene) was first “coined” in 1631. Curiously, the author leaves the even more cynical multiple acts of Enclosure (which first began to proliferate under the Tudors) unexamined.

A second Mount-ian (or should that be “Mountainous”?) avalanche of sentimentality occurred on the sixth of November, 1740 (presumably around tea-time) with the publication of Samuel Richardson’s debut novel, Pamela: or Virtue Rewarded. This Mills and Boon-style production was, apparently, the precursor to Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (which, possibly, occasioned a spate of copycat suicides), Rousseau’s Confessions and, ultimately, the vapourings of Robbie Burns, William Wordsworth and the whole “Romantic Movement”.

Following a near-dialectical retrenchment of “manliness” (ushered in by the French Revolution’s “Terror” trials and the Napoleonic wars) the Victorians – for all their protestations of “muscular Christianity”— seem at once, and slightly to the confutation of Soft‘s central argument, both cloyingly sentimental and profoundly philistine. Anyway, the Modernists and World War One, Mount opines, put paid, temporarily at least, to sentimentality’s last remnants.

Mount does make some telling points. During the eighteenth century “…the Church of England gained, and has never quite lost, a reputation for complacency in the face of injustice…” He exposes the essential snobbery of the Bloomsbury set. He also takes a heartfelt thwack at Picasso’s “Guernica”: “if you do not know the painting’s title and occasions, its, well, its gaiety might even make you smile a little”.

But Soft contains many moments of digression which do not really advance its author’s contentions. His dissection of a literary tiff between those two former friends, Victor Hugo and Alphonse de Lamartine, rumbles on, for example (and with various “noises off” from the likes of Baudelaire, Flaubert, Gide and Gautier) for fourteen less than enthralling pages.

It is perhaps possible to believe that sentiments can be held without their host becoming either unduly sentimental or subscribing to its less salubrious cousin, sententiousness. Like most conservative politicians – and certainly his cousin Lord David Cameron – Mount fails to challenge, or even acknowledge, the fundamental paradox that one person’s “economic freedom” traditionally equates to at least a few dozen others’ “economic servitude”.

However, despite a lingering distaste for his assertive style, it is generally quite difficult to fault his scholarship. Only once was this reviewer able to detect an error when Mount (wrongly) adduces 1895 as the date of the first publication of Kipling’s famous poem, “If”. To be fair, this is also the year erroneously given for its composition by that near-infallible scholastic tool “Wikipedia”.

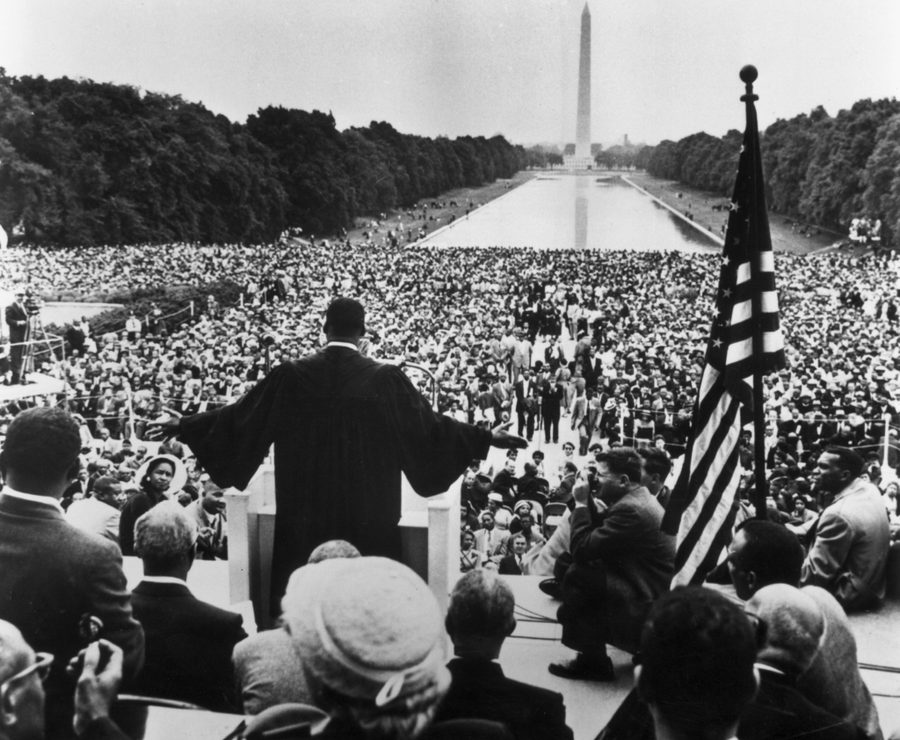

The third “sentimental revolution” occurred (if we are to accept Philip Larkin’s judgement) in 1963, “Between the end of the Chatterley ban/ And the Beatles’ first LP”. Or was that merely “sexual intercourse”? It (sentimentality) reached its questionable apotheosis“on or around” September, 1997, with the funeral of the so-called “People’s Princess”, Diana Windsor – a celebrity divorcee and international playgirl dabbling in charitable causes and whom very few of her Over The Top mourners had ever met. A regal obsession with protocol (specifically the propriety or otherwise of half-masting flags) would have had Highgate’s prophet, Karl Marx, gurning into his beard. Tragedy had finally transposed into farce. Since then we have, allegedly, been in a sort of slow descent, perhaps towards a renewed age of compassion fatigue/ cultural amnesia.

Ferdinand Mount is formidably well-read and his frames of reference are genuinely eclectic. Having enjoyed some of his previous works (notably Mind the Gap [2004] and English Lives [2016]) I expected to be both amused and informed by this one, but Soft borders, at times, on preachiness.

Whilst I can, and do, sympathise with much of his central thesis (that mankind is essentially the better for acknowledging its capacity for “sentiment” – a.k.a. “sympathy”, “tenderness” or “benevolence”) it ill-behoves one of Margeret Thatcher’s Bright-Young-Men-of-the-Eighties (he was head of her policy “Think Tank”) to lecture us about it. For those of us old enough to remember, that appalling “Iron Lady” was responsible for more long-term societal division in Britain than almost any other individual of the twentieth century. Not that she believed in an entity called “society”. Mount demonstrably does – and seems to be of the opinion that it is, periodically, capable of being “soft” – perhaps he really means “kind”. After a lifetime spent watching the British social and health services in which I worked being systematically degraded by successive governments, and being “educated” on the subject by such as Mr Mount, I’m not wholly certain I agree.