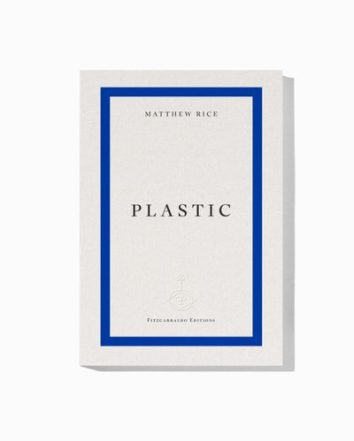

Plastic, by Matthew Rice, Fitzcarraldo Editions, is available here

By Nick Moss

For most of the period since at least the publication of The New American Poetry 1945-1960 there has been a division between poets. Some see poetry as social poetics – characterised by what the poet Mark Nowak called:

…a radically public poetics, a poetics for and by the working-class people who read it, analyse it and produce it within their struggles to transform 21st century capitalism into a more equitable, equal, and socialist system of relations.

There are also poets who align more closely with what became known as the language school of poetic practice, which saw poetry as, essentially, “the philosophy of practice in language”.

This latter tendency drew on the theoretical work of Jacques Derrida (Of Grammatology in particular), Ferdinand de Saussure, and Roman Jakobson, and was always vulnerable to the critique that, as one of its key writers, Ron Silliman acknowledges, poetry was subordinate to theory. Silliman also undermined the reception of his best arguments by contending that:

I am aware that the tradition within which I work is an option that has most readily been available within the culture of educated, white men. That this does not represent the whole of society in no way invalidates its own legitimacy.

For those operating within the field of “social poetics” these words were taken as arguing that poetry produced outside the academy had no relevance. In fact, Silliman meant the opposite – his argument continues:

…..If anything, it is imperative that we come to understand what this hegemonic tradition has meant, and may yet mean, within a larger sphere of action, even as we insist on the necessity of weaning it (or us) of its (our) desire for domination.

Silliman’s argument is that within the academy, for:

…some of bourgeois poetry, the recognition of the construction of the individual through ideology, by means of language and other codes, is not an intellectual game…(but reflects) a similar fissure within the bourgeoisie itself – an opposition whose goal is not domination by class, but an end to all relations of power predicated on human difference.

The language school poets therefore understood poetry as a form of ideological critique – a way of disorientating and disrupting the languages of power, but one predicated on an absolute honesty about their own roots within and against the academy, and an understanding of the nature of poetry as part of the culture industry.

Rich, strange and dreamy

It is my contention that the two forms of poetic practice need not be in opposition. The methods of the language school – whether it be their desire to experiment with form, or the kind of long-form poetic autofiction pursued by Silliman and others such as Rae Armantrout and Rachel Blau DuPlessis, are resources than can be taken up by working-class writers outside the academy.

Fran Lock has also recently argued for this:

over time, the material pressures and distortional stresses under which poor and working-class poetry is made have come to entail a particular aesthetic idiom. this, in turn, has allowed working-class poetry to be siloed inside of style. worse, to be over-determined by a limiting set of characteristics. that our work not only is, but must be short, direct, punchy and plain-spoken; that our work must centre material conditions and besetting political urgencies. as if we had no reflective impulse. as if we had no interiority – no subjectivity – at all. against this, then, against the reduction of our lyric imagination, the long poem also unfolds as an act of self-assertion, tenderly insisting on its right to be rich, strange, dreamy, delving, and maximalist.

My argument here, then, is simply that working-class poetry has a right to be whatever it wants to be. By embracing the ethics of social poetics as a “radically public poetics” we do not thereby relinquish our right to be “rich, strange, dreamy.”

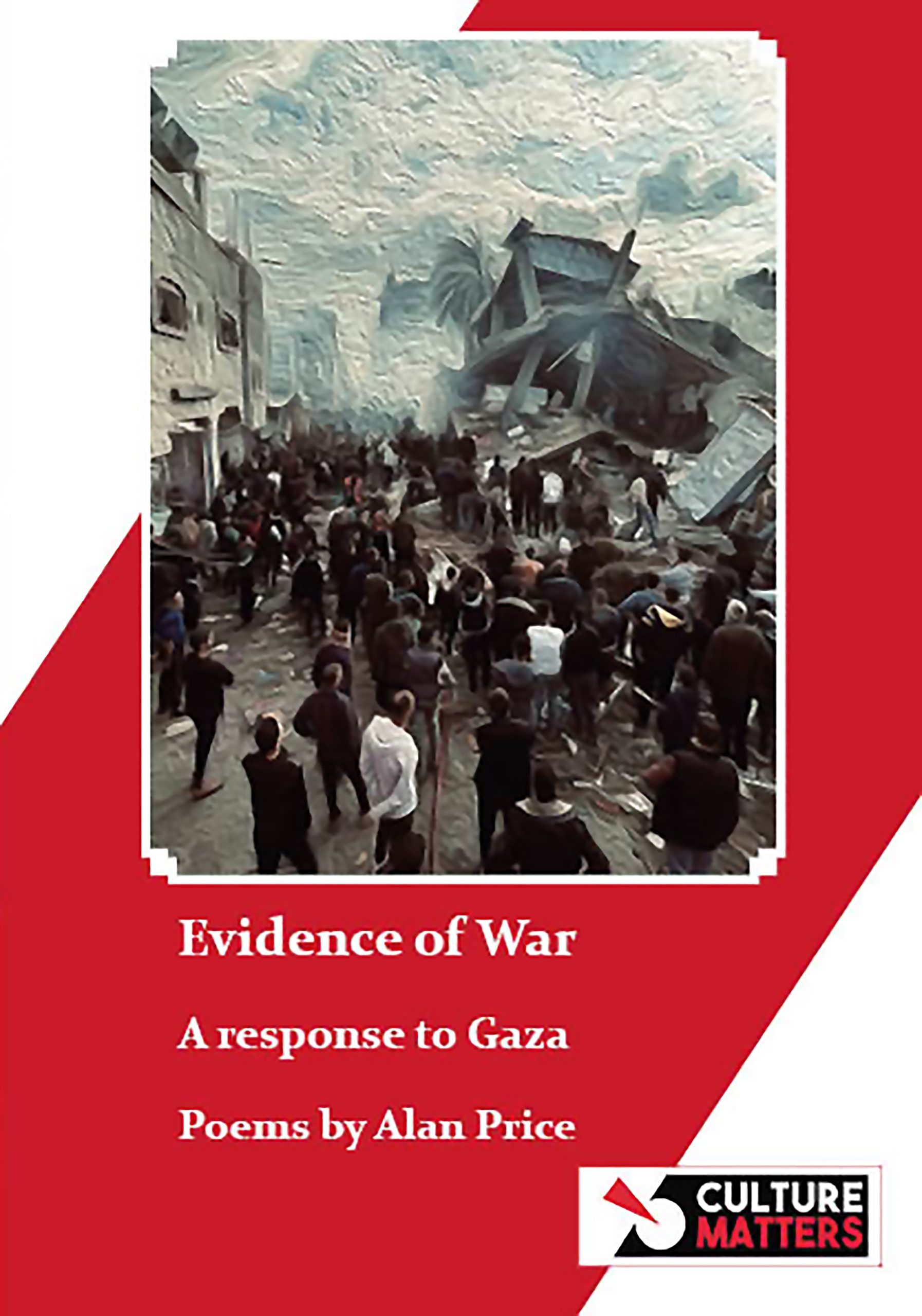

All this is by way of drawing attention to a forceful new book. Plastic, by Matthew Rice (Fitzcarraldo Editions 2026) is that all-too rare thing – poetry about work. Specifically, it is about a night shift producing aeroplane parts in a factory in Belfast; and in the process it claims also the right to experiment with form.

Rice is already a poet of some renown. His first book, The Last Weather Observer (Summer Palace Press 2021) was included in the Arts Council of Northern Ireland’s top 10 books of that year. However, Plastic is a braver and more confrontational work and deserves to be recognised for its attempt to both portray the despair of low paid, alienated labour and try to sketch a way out, despite the decline of working-class militancy which has resulted in such an oppressive, futureless, fractured workplace.

The poems chart moments during the long stretch of the night shift. The formal experimentation is subtle – it starts with the integration of the Gawain tale into the poetry, initially by reference to the poet’s own reading of the poem: “and my copy of Gawain / is contraband beneath / the frosted-out skylight.” and then by inserting references to the tale throughout.

The Gawain reference irks at first – it’s supposed to, I think. It deliberately sets the writer apart from his fellow workers, in the same way that the poet Fred Voss’s references to his having chosen to leave academia to work in a factory sometimes irked. What it also represents, though is the refusal of the cage of a working-class identity defined by capitalist logic, and it places class struggle within the context of a battle for self-definition, of which the production of poetry is a part. This gives rise to the second element of Rice’s formal experiment – producing a poetry that reckons with and references Jacques Ranciere’s book Proletarian Nights.

Ranciere was one of the co-authors of Louis Althusser’s Reading Capital, who subsequently split from Althusser over the issue of working-class spontaneity, and the recognition of “a thought and history from below.” Rice quotes Ranciere in his epigraph to Plastic – “the question of maintaining or transgressing the barrier that separates those who think from those who work with their hands.” This implies a double meaning at the heart of Plastic – both the plastic used as a material of production by the workers in the book, and the plasticity of the concepts of working and thinking. The coming-to-consciousness of the working class has to involve the overcoming of the divide between working and thinking, realising the plasticity of the false separation.

As Karl Marx explained it in The German Ideology:

…as soon as the distribution of labour comes into being, each man has a particular, exclusive sphere of activity, which is forced upon him and from which he cannot escape. He is a hunter, a fisherman, a herdsman, or a critical critic, and must remain so if he does not want to lose his means of livelihood; while in communist society, where nobody has one exclusive sphere of activity but each can become accomplished in any branch he wishes, society regulates the general production and thus makes it possible for me to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner, just as I have a mind, without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic.

Plastic, then, is about how we get to this, and how thinking about work, at work, and daydreaming at work, about having another life elsewhere, might be steps along the road.

Rice maps out the specific context of the factory within which he works. It carries the scars of sectarian division as an obstacle to overcoming oppression: “…the factory radio blaring / Tina Turner’s The Best”; “The relationship between touchscreen and finger / is unbearable, like the Twelfth roadblocks / sprung with fire.”

All of this is manifested also in bleakly circumscribed lives outside work: “Granny’s house was targeted / three times because my uncle / was on a hit list”; and:

The last time I flew Flybe

I recognised my own handiwork

in the pristine edge

of the end bay that made up

the seating’s lower half

four hours to Italy –

even on holiday,

even at thirty thousand feet,

at five hundred miles an hour,

you can’t escape.

There is a dark wit in this last poem, but equally, if ever you wanted a definition of the worker alienated from the product of his own labour, Rice captures it here – where your own work only produces something you can’t ever get away from, even by way of a holiday.

Cannon fodder or factory fodder

What Rice is really good at mapping out are the daily indignities of shite work. In this, he’s similar to Martin Hayes – delivering up a droll, biting, minute-by-minute record of slow degradation:

Ghostly in hi-vis the night guard

gives voice to the hour echoing into

the next and retains no prospect but of trees

and all the dark and chilling dew.

And:

Man is born free, and everywhere he is in supply chains –

it’s a bit like this place,

tethered to the machine

with an option to go hungry, or find another factory

to feel the same in.

And:

How I rehearse each shift

to justify myself to myself,a cell made up of cells in a cell

whose cells are altered daily

by breathing the factory air, peculiar

with cryptic chemicals drawn

from distant ecosystems.

And all of this work is borne under the weight of how it has panned out for some here, not too long before:

Once in this building, a kid clocked off night shift

for good at the end of a rope,

another’s heart gave out at 3 a.m

performing at task as menial as mine.

Rice writes with unadorned, bleak clarity, and with a bitterly cruel irony. In 20:59 we get Tommy Cope, ex-squaddie:

tasked with keeping prisoners awake

he tells me, when he served in Afghanistan.

He knows by heart every word of AC/DC’s Hell’s Bells

“See this” he yells, raising hell

with a piece of pipe on a bin lid

“Every fifteen fuckin’ minutes”

By 21: 07:

Tommy Cope takes it upon

himself to lower the heaviest tool

in the factory…. the tool unhooked and finally tipping,

all one ton of which Tommy Cope

takes upon himself to catch,

his crushed wrist and hand

from which, at 21:07

blood escapes.

To quote Hell’s Bells: “My lightning’s flashing across the sky / You’re only young, but you’re gonna die.” Cannon fodder or factory fodder. Some choice.

What there is little of in Plastic is the kind of pride in craft that crops up in the poetry of Fred Voss, Martin Hayes or William Letford. Work here maims, poisons, causes cancer, exploits, drains, kills. There are occasional flashes of optimism, like Gail in 05:29:

shifting defective ring washers

from those within tolerance and

her bench could be a grand piano

her patch of floor a stage

and in another life, it is.

Except that Gail is 70 and still grafting away at the factory. And any joy in skill is in “another life.” In this life “The job card says URGENT! / ’cause these parts were due yesterday / and I’m fucked if I can’t pay the rent” (23:06); “and who knows / who I wanted to be / in that past whose future / never came.” (08:00).

So how to resist, how to refuse despair, in the absence of collective resistance? Rice, like the Ranciere of Proletarian Nights, offers us a dreamscape of imaginative revolt:

Night Shift

Always on the drive to the factory, I visit

somewhere I’ve never been, Amsterdam

sometimes, a gust of gulls sown

over the Singelgracht.

We survive by seizing onto the detritus of our past dreams and the past dreams of others –

the things that ignited our imaginations when we were kids, or running-wild teenagers, dreaming mad dreams of lives bigger and wilder than the regime of the night shift will allow:

Crazy Dale’s old Marvel comics

piled in the canteen by the kettle

– 21:48

It’s only in dreams you’re truly free…I was where the hanged men

were raised above the shifting earth

a rat-person in dream-clothing

watching the condemned/soaring on barley wine

as if drunkenness might stand in for death

– 22:22

In three poems, 00:25, 00:26 and 00:27, Rice notes:

a dent so gaping it’s the mouth on the cover

of Music for the Jilted Generation

– 00:25

another piece of my childhood…Keith Flint no longer here-checked out

over the weekend…The last photo of him on the internet

shows him setting a personal best

during his local parkrun, smiling/his biggest, broadest smile.

He looks like the happiest little boy.

– 00:26

They filmed the video for Firestarter in a disused

Underground tunnel near Aldwych

the same tunnel where artworks and artefacts sheltered

from the Blitz…A photo online…A little boy snuggles into his mum

He looks like a 1940s Keef. For him that tunnel is the whole world

the total discrediting of reality.

– 00:27

And how desperate is that need to discredit reality, when as Rice outlines in fragments throughout, reality is “the misery of concrete”, or a wind-up jumble sale Evel Knievel toy “which smelt of nicotine, whose burnt-out mechanism / had long been shot to shit.”

In Plastic, Rice gives us “Hell as an idea of what work could be.” He also, though, points to a way out. In lieu of militancy, as a prelude to militancy perhaps, he gives us imagination – he gives us escape via a “dog -eared Gawain”, he gives us “the myth of the four-ball plant / I made true by fluke” that’s accidentally just like a shot Paul Newman made in the 1961 film The Hustler. In 06:15 he gives us himself, on the toilet at work, opening the “notes” app on his phone and beginning to type the first draft of an untitled poem that then appears on page 13 of the book.

The working class for-itself will necessarily be made up of working-class people who have discovered themselves as subjects-for-themselves. Part of this will involve rejecting capitalism’s idea of what working-class identity and subjectivity are reduced to. Thus, for Rice, as for Ranciere, subjectivity can be formed as an act of self-realisation through creativity:

I skive

I resent…I outlast

I barely last.

– Prologue, p16.

Resistance can, as a start, be composing a poem in the jacks. It can be reading Gawain in the boss’s time.

Silliman said that “The social role of the poem places it in an important position to carry the class struggle for consciousness to the level of consciousness.” This what Matthew Rice achieves in his beautiful, angry, grimly funny book.

Resistance to ICE

Resistance to ICE in Minneapolis has taken many forms. Faced with a bunch of racist stormtroopers trying to snatch their neighbours, people have marched, fought, and filmed. They have provided solidarity by way of alerting their neighbours that ICE are around. They have organised school runs for the children of migrants and provided food. They have been shot down and killed for this.

The determination of the fightback has been an inspiration for those of us here who are faced with proposals for some of the same – both by Farage, by Badenoch, but also, with a more genteel “don’t alarm Polly Toynbee” face, by Starmer and Shabana Mahmood. In staring in horror at our TV screens, we should remember that the UK Border Force already conducts dawn raids here, and if we are inspired by the resistance in the US, maybe we should be doing more of that in the UK.

Cultural resistance has been comparatively thin on the ground, but there have been a number of responses. Neil Young has spoken out against Trump and his tech-bro backers since the start of Trump’s first term, as has Bruce Springsteen, whose song Streets of Minneapolis is a powerful takedown of the Trump regime and its war against the immigrant poor, and is sung with a venomous, righteous anger.

I want though to draw attention to Everlast x WLPWR – Blood on the Wheel (FUCK ICE). Everlast was the main rapper in House of Pain, the Irish-American / Latvian trio who had a hit with Jump Around in 199 2. Since then, Everlast has performed as a solo artist, blending rap with a grizzled, melancholy folk-blues that has sought to remain true to its blue-collar US constituency. What makes Blood on the Wheel important is its injunction that “the black community told us this shit for years, we didn’t listen” and, crucially, these lyrics:

Now they don’t care none

Badges they don’t wear none

But soon enough we’ll all be shooting back at you

There really ain’t a fucking thing you can do

We got way more guns we got way more goons

At a time when Trump has managed to piss of the National Rifle Association, Everlast’s point is a simple one, and should be borne in mind by anyone who thinks US gun laws and the right to bear arms are things the Left should campaign against. In their song Five to One, the Doors sang “They got the guns / But we got the numbers.” Everlast’s point is a twist on that – the “people” in the US have, potentially, both more guns and more numbers than the state they are facing down.